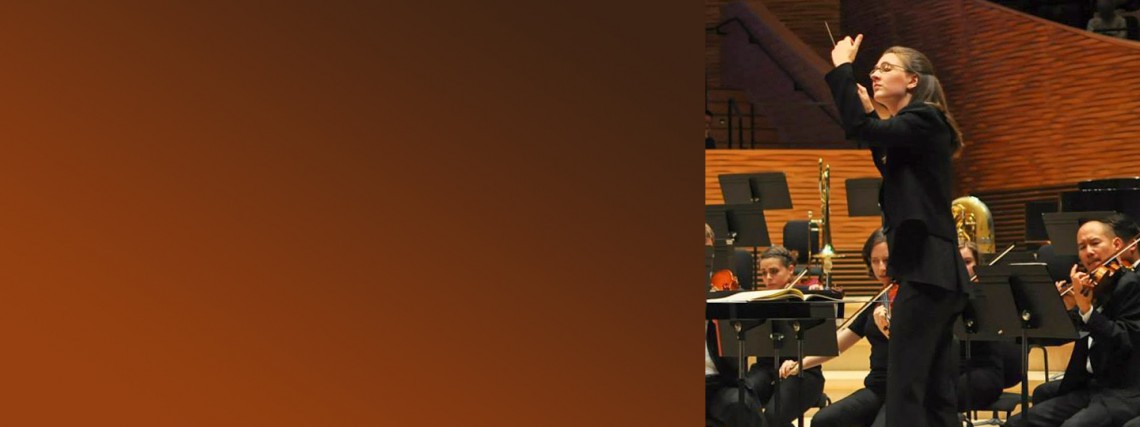

Photo by Jimmy Zhang

Anna Wittstruck, a Stanford graduate student in music, conducts orchestral performances in between writing her dissertation on European ballet music during the 1920s and '30s.Music scholarship and dance performance come together in Stanford scholar’s study of interwar music

Through a study of the relationship between music and dance in ballets produced between the two world wars, Stanford graduate student and conductor Anna Wittstruck illustrates how composers sought to bring audiences together.

Music graduate student Anna Wittstruck is a unique combination of performer and scholar.

The orchestral cellist currently conducts the Stanford Wind Ensemble and has conducted the Summer Stanford Symphony Orchestra for the past five years. She has also conducted in the Orchestral Studies program at Stanford.

In the midst of all this conducting and performing, she’s also completing a dissertation about European ballet music composed between the two world wars.

She is one of a few musicologists to use the vocabulary of dance, ballet in particular, to investigate interwar music. She is also one of the first scholars to focus on how social dance topics transformed classical music made between 1924 and 1938.

“There’s this profound moment after the First World War when it’s as if all of Europe needs a group therapy session,” Wittstruck explained, also noting that World War I “is one of these definitive moments where everything changes in the arts, and it’s in reaction to this [postwar] moment that everyone is experiencing together.”

Wittstruck’s research combines dance scholarship with music history in an examination of three ballets written between the two world wars – The Seven Deadly Sins by Kurt Weill, Les Biches (meaning “does,” or female deer) by Francis Poulenc and Horoscope by Constant Lambert.

As a result of looking at the relationship between music and dance in her case studies, Wittstruck offers a new history of interwar neoclassicism, which strove to restore order, balance and restraint in music.

Keenly aware of how research and performance can be “mutually enforcing,” Wittstruck said she appreciates the freedom she has at Stanford to both perform and conduct scholarship.

For instance, last May, Wittstruck conducted the Stanford Philharmonia Orchestra in a performance of Weill’s The Seven Deadly Sins, a ballet chanté (sung ballet) that also happens to be one of the compositions in her dissertation.

“I knew the music so well from studying [The Seven Deadly Sins], that it was a different kind of preparation for rehearsal because it was music that was part of me. And so it was actually much easier to conduct,” she said.

This give-and-take between her performance and academic work truly inspires the scholar, who has performed as a cellist with the YouTube Symphony Orchestra.

Conducting, playing music and research are all important practices for her. Wittstruck said her long-term goal is to have “music performers and researchers fruitfully engage with one another.”

Rescuing neoclassicism

Through her investigation of interwar music, Wittstruck has uncovered compositions and ballets that draw on contemporary fashion, dance and popular music, particularly jazz. She uses these ballets to counter the traditional assumption that neoclassical music nostalgically reveres the past.

She asserts that neoclassical music was actually a response to another kind of music. Before the First World War, composers used chromatic and atonal sounds to create a jarring experience for the listener. Such music underscored the alienation of the individual.

According to Wittstruck, after the war “instead of individual musical expression, some [composers] return to forms and tropes, and make references in music that two people in the same concert hall will get at the same time.”

Wittstruck said these familiar forms, such as the waltz or the foxtrot, were regularly used during this period between the two world wars as “an important way of grounding the audience and having them experience the same thing together.”

Neoclassicism is not just about putting the past on a pedestal, she said, “it is about using past forms and references to find innovative ways to move forward and forge communities, so that the experience of art is not something alienating but something that brings people together.”

Wittstruck has found that interwar composers were not just looking to classical forms; many were looking at what was going on in popular culture from the sounds of taxi horns to the music heard in jazz clubs. They drew from jazz and other world cultures for inspiration and incorporated those sounds into their compositions.

For instance, Wittstruck said, Francis Poulenc included jazz elements in works like Les Biches. Hearing jazz in a neoclassical ballet connected audience members to other group experiences like that of social dancing in a jazz club.

“Poulenc was a jazz pianist and would be in these clubs all night,” Wittstruck explained. “So popular dance in the earlier 20th century becomes very important and integrated in art music.”

Controversy swirls around the history of neoclassical music, however, because music seen as good for community and collectivity became very interesting for the Nazis to appropriate, Wittstruck noted.

“So part of what I’m trying to do in my work,” she said, “is rescue neoclassicism from this tainted reception history of being associated with fascism.”

Reconstructing choreography

Wittstruck challenges traditional perceptions of neoclassicism by carefully examining the choreography of her case studies.

An experienced ballet dancer, Wittstruck wondered about the staging and choreography of the ballets she was researching. Her visits to archives in Paris, New York and London led her deep into the world of choreographers like Bronislava Nijinska, George Balanchine and Frederick Ashton.

“This is a very challenging project because a lot of this choreography we don’t have,” Wittstruck said.

She draws on a few rare videos of revival performances in order to reconstruct the movements, steps and patterns of dancers. But she also relies heavily on photographs, original scores, letters, correspondences and reviews.

Another dimension of Wittstruck’s dissertation is her effort to recover the works of Constant Lambert, a composer, critic and conductor, much like Wittstruck herself. Despite being an intriguing character, Lambert has not been extensively studied.

Lambert’s Horoscope is an interesting case, she said, because the sets, choreography and orchestral score were all lost when the Vic-Wells Ballet troupe fled a German invasion in the Netherlands. Wittstruck said the ballet has never been performed again, and the music is rarely heard in concert halls.

“I would love to think about staging the Constant Lambert ballet, reconstruct or reimagine the choreography the best that we can, and have the first revival since 1940,” she said.

She lights up at the prospect of such a task, where her performance and scholarship could again intersect. This co-mingling is very much a part of Wittstruck’s vision.

“If you can get performers to be inspired by the historical background and the way the music is constructed, and if you can have scholars implement their own expertise in producing and performing music, then I think each professional category will be enriched,” she said.