PhD candidate explores Persia’s Safavid Empire in her exhibition at the Cantor

The Safavid era (1501–1722) is a fascinating epoch in Iranian history, yet unfamiliar to many. When the Safavids came to power, they brought a huge expanse of territory—stretching from modern day Iraq to Afghanistan—under their control. With different cultures and ethnicities under their reign, the arts played a key role in developing a cohesive Safavid visual identity. At the same time, contact between Iran and Europe was accelerating. This exchange and the opening of new diplomatic and commercial routes between Persia and Europe is the centerpiece of Stanford University art history PhD student Alexandria Hejazi Tsagaris’ exhibition Crossing the Caspian: Persia and Europe, 1500–1700, which is part of the Cantor Arts Center and Department of Art and Art History’s joint Mellon Curatorial Research Assistantships program funded by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

The exhibition is on view in Cantor’s Lynn Krywick Gibbons Gallery through April 26, 2020, and a catalogue is available online. Hejazi Tsagaris will give a talk on Feb. 19 at 5:30 p.m.

How did your educational experience lead you to explore this topic?

My discovery of Safavid art began in 2015 while enrolled in Stanford’s Ubaldo Pierotti Professor of Italian History Paula Findlen’s seminar “Coffee, Sugar, and Chocolate: Commodities and Consumption in World History.” I wrote a paper on an unidentified Persian manuscript in the Cantor’s collection for my final project. I later learned it was a 17th-century manuscript of the poetry of Rumi, made in the Safavid capital of Isfahan. Ever since then, I was hooked. That research led to my dissertation topic, artistic exchange between Safavid Persia and Italy.

Is the exhibition primarily drawn from the Cantor and other Stanford resources?

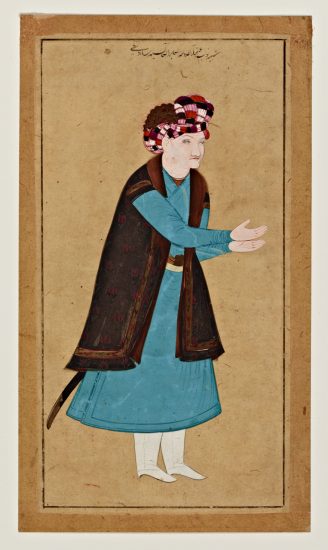

When I applied for the curatorial fellowship, I was unsure whether there would be enough material related to Persia at Stanford. It turns out we have a wealth of remarkable material right here on campus—Persian miniature paintings, blue-and-white Safavid porcelain, drawings of Persian figures, themes made by European artists, and much more. From Special Collections, we included two very rare European books and two beautiful maps of the Safavid kingdom that illustrate the dramatic change in the geographical knowledge of Persia during this period. We’re fortunate to have some wonderful objects on loan from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco as well.

Are there examples of how diplomacy and artistic exchange intersected?

Absolutely. Without a shared spoken language, visual art became the primary vessel of intercultural communication, often accomplished through the exchange of diplomatic gifts such as silk textiles, portraits, books, and paintings—but also through the visual recording and memorialization of those diplomatic visits, recorded in palatial frescoes, circulated prints, news pamphlets, and so on.

What insights would you like visitors to take from this exhibition?

My fervent hope is that this exhibition sparks curiosity and wonder in the arts of Persia and encourages people to delve more deeply into its connection to the global sphere. As many of us seek to overcome social, racial, and religious stereotypes, I believe it is more important now than ever to highlight the agency of art as a mediator of difference and an instrument of exchange, knowledge, and collaboration.

This story will appear in the spring 2020 issue of the Cantor Magazine scheduled to publish in April. Click here for back issues.