Stanford exhibit spotlights medieval ‘world of words’

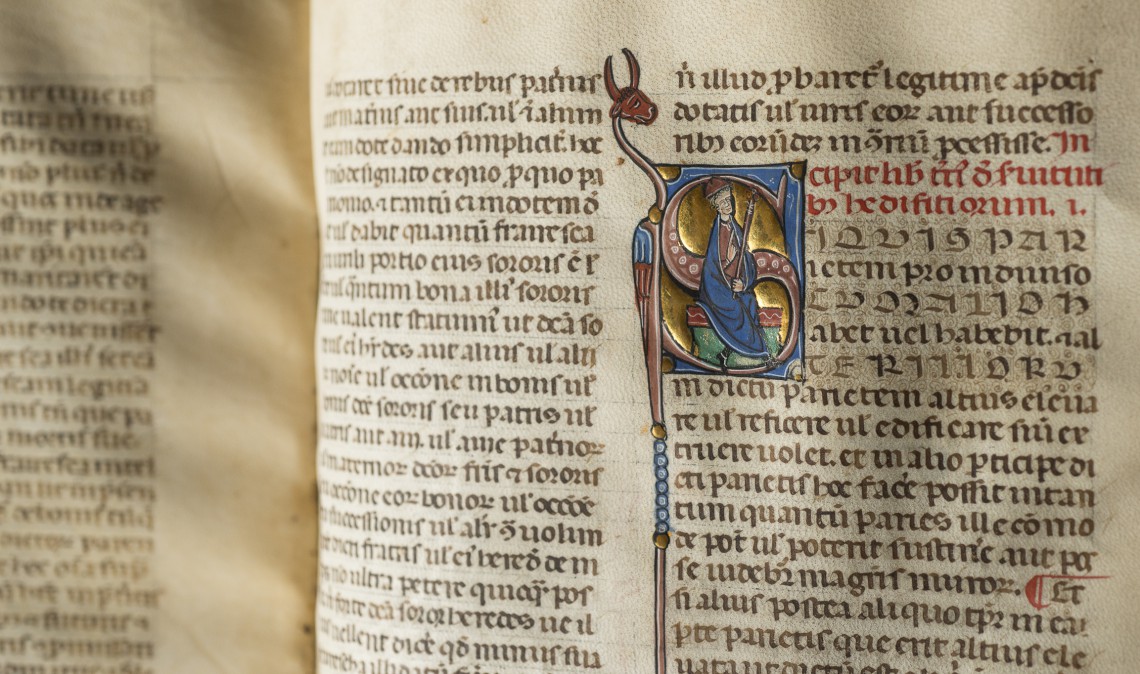

The Circle of the Sun exhibit draws on Stanford's medieval and early modern manuscript holdings, including a number of recent acquisitions, to show how secular learning was shared and spread throughout the Middle Ages.

Open a book, and you discover a whole new world – especially if that book is several centuries old.

That is the case with The Circle of the Sun, a new Stanford University Libraries exhibit on display through June 14 in the Peterson Gallery and Munger Rotunda of Green Library. It features the secular works in Stanford’s medieval and early modern manuscript collections – all valuable resources for scholars and students alike to draw upon in their research.

The Circle of the Sun examines the seven liberal arts in Western Europe from the 9th through the 17th centuries as well as the rise of professions in law, medicine and commerce; and the emergence of scholastic philosophy, history, vernacular literature and Renaissance humanism.

During this period, parchment gave way to paper, and an increase in literacy among the general population resulted in a heightened demand for manuscripts throughout Western Europe.

One can see the physical manifestation of the West’s literacy and education boom in the roughly 75 objects or documents on view in 20 display cases.

Highlights include works by Ovid, Virgil and Cicero; astronomical and legal texts; a portrait of Geoffrey Chaucer; medieval poetry; and fragments of rare treatises on Latin lexicography, etymology and allegory.

Visitors will also see a selection of Roman writing implements, coins and inscriptions as well as goatskins prepared as parchment by a modern artisan.

“They wrote on anything and everything,” said David Jordan, associate curator for paleographical materials, who co-curated the exhibit along with student Sarah Weston, ’14.

The Circle of the Sun is the second of a two-part exhibit designed to show the full spectrum of available Stanford manuscripts for teaching and research. Last year’s installment was Scripting the Sacred, which was also co-curated by a Stanford student. It spotlighted the religious medieval manuscripts – such as Bibles and the Books of Hours – in Stanford’s collection.

“From antiquity, scholars divided knowledge into res divinae (sacred) and res humanae (secular),” the exhibit’s introduction noted.

“Our exhibit includes manuscript fragments that Stanford researchers and students, including Sarah herself, helped to decode and decipher over the last two years,” Jordan said.

These materials are regularly used by researchers from nearly all of the humanities departments, and especially by students and faculty at Stanford’s Center for Medieval and Early Modern Studies.

Paleography is the study of old handwriting and the key to understanding how Stanford selected the materials for the exhibit, said Jordan. Specifically, paleography is the practice of deciphering, reading, placing and dating historical manuscripts, and understanding the cultural context of writing, including the methods with which the codices were produced.

Paleography, explained Jordan, was first used scientifically to detect forgeries in diplomatic documents; its principles were later applied to related academic disciplines such as epigraphy, textual criticism and codicology, which are also discussed in the exhibition. The whole process from conceptualization to exhibit takes about two years, he said.

“Each show,” said Jordan, “is a collaborative effort between curators and the exhibits manager and designer for the Libraries’ Special Collections, Becky Fischbach, who physically prepares and installs materials and designs and produces the display texts and graphics.”

Today, manuscript studies is an emerging and growing field. It is both highly interdisciplinary and increasingly technical – for which paleography, the study of old writing, remains a fundamental tool. After all, societies and civilizations are shaped by the way they transfer and share their knowledge among their people, whether prince or pauper.

One sees in the exhibit that this rediscovery of knowledge within ancient and medieval manuscripts had brilliant historical outcomes. This is reflected in the Carolingian culture, the rise of cathedral schools and universities, Scholastic philosophy, the emergence of the rule of law, the growth of the trades and Renaissance humanism.

In the world of deciphering manuscripts, hidden knowledge awaits the limelight.

“Much remains to be rediscovered,” Jordan said.