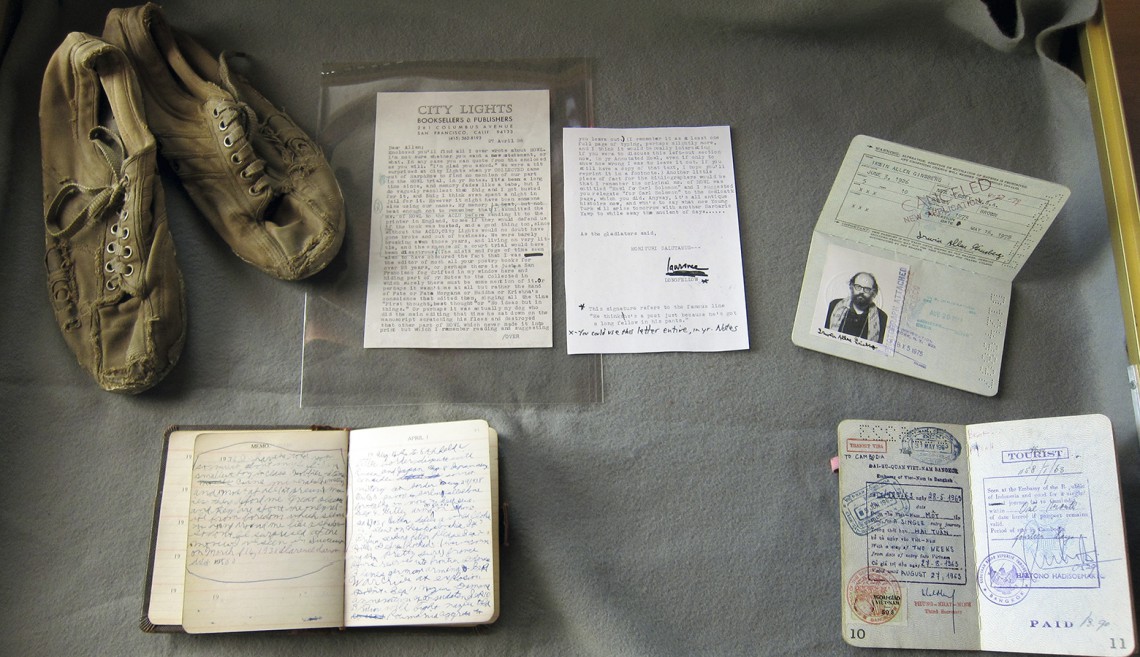

Among the items from the Allen Ginsberg Papers collection at Stanford are a pair of Ginsberg's shoes and a letter from Lawrence Ferlinghetti, co-founder of City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. Archivist Bill Morgan said Ginsberg saved the poorly made sneakers, which he bought in then-communist Czechoslovakia, because their shoddy appearance illustrated the harsh realities of communism.

Veronica MarianThrough photos and memorabilia, Stanford’s Allen Ginsberg collection captures a generation

Bill Morgan, the personal archivist to the acclaimed Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg, says that Ginsberg's legacy is as much about what he left behind as it is about his life and work. Everything from childhood diaries and personal correspondence to first editions of Ginsberg's works and all manner of printed ephemera make up the nearly 1,300 linear feet of material in Stanford's Allen Ginsberg Papers collection.

Allen Ginsberg, the iconic figurehead of the Beat Generation, saved just about everything.

Ginsberg’s vast array of memorabilia housed in the Stanford University Libraries’ Department of Special Collections proves that he was not just an observer of culture, but also a collector of culture.

Bill Morgan, Ginsberg’s personal archivist, bibliographer and biographer, told a Stanford audience last week that “Allen saved everything since he was a little boy because he knew he’d be famous one day.”

Veronica Marian

Morgan, who worked closely with Ginsberg from the early 1980s until Ginsberg died in 1996, spoke to an audience at the Stanford Humanities Center about the Ginsberg archive, which Stanford acquired in 1994 under Morgan’s direction.

“Allen never let anything go, and everything that he saved in his life is in the archive here,” Morgan said – unless, he joked, something was “stolen by one of Allen’s larcenous friends, of which Allen had many.”

Organized by the Stanford Humanities Outreach Project and San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum (CJM), the talk gave attendees a rare opportunity to view items held in the Stanford Libraries’ Special Collections and to hear from one of the people most familiar with Ginsberg’s life and works.

The archive is a treasure, said Stanford literary scholar Hilton Obenzinger, who introduced Morgan and joined him in a conversation that explored the legacy of Ginsberg’s cultural contributions. “Despite complaints by those offended by Ginsberg’s work and the whole legacy of the Beats, Stanford made a brilliant decision to acquire the archive of one of the great American poets of the 20th century.”

Seemingly less important items, such as an old pair of sneakers and beard clippings, drew criticism of Stanford’s purchase of the archive, but Morgan said Ginsberg kept each item for a reason.

Pointing to the sneakers in the display case, Morgan said they were given to Ginsberg in 1965 when he visited then-communist Czechoslovakia. Poorly made and tattered even when they were nearly new, Morgan said Ginsberg kept the sneakers because their shoddy appearance illustrated the harsh realities of communism.

And the beard clippings? Morgan said that Ginsberg “never valued money except for how it could help others” and saved his trimmings from time to time so that charities could make money selling them at fundraising auctions.

The talk was presented in conjunction with the CJM exhibition “Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg,” which showcases one of Ginsberg’s lesser-known talents – photography.

On display until early September, the exhibition features 80 photos taken by Ginsberg, but as Morgan pointed out, all 80,000 of Allen Ginsberg’s photos (and corresponding negatives) are on the Stanford campus.

Photographer of a generation

Morgan, who spent 20 years cataloging Ginsberg’s materials, said the organization process spurred Ginsberg’s interest in photography.

In the early years of their working relationship, Morgan continually came across unidentified photos as he pored through boxes upon boxes of Ginsberg’s ephemera. Morgan nagged Ginsberg to identify the people in the photos, and when Ginsberg finally started to review them, Morgan said, Ginsberg realized his images “were not only the history of the people he knew” but were also “kind of good works of art.”

So Ginsberg, who had taken about 1,200 photos before he put photography on the back burner in the early 1960s, consulted his friend and photographer Robert Frank on photography techniques, and between 1982 and his death in 1997 took “the other 78,800 photographs,” Morgan said.

Allen saved everything since he was a little boy because he knew he’d be famous one day.

Friends, including Beat Generation icons Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs and Neal Cassady, were among Ginsberg’s favorite subjects.

Ginsberg “wanted to document his friends and took great pictures of them because his friends were so comfortable around him,” Morgan noted. Detailed captions on many of the prints enhance their historical value.

Morgan said that when “Allen started printing up the pictures as enlargements, he started to caption the pictures on the front.” Ginsberg got the idea, Morgan said, from photographer Berenice Abbott, “who had always written a caption for her photos on the back, but Allen being more literate decided that he would put it on the front of the photograph.”

When Ginsberg printed a photo he would “start with the old caption and he would re-write it so that no two captions for the same photograph were ever alike,” said Morgan.

As with Ginsberg’s most famous shot, of Jack Kerouac standing on the fire escape, subsequent captions built on one another and got increasingly longer with each re-print. “The person developing the enlargements had to continually make the photograph smaller and smaller to accommodate the longer and longer caption,” Morgan said.

Versatile collection

Ginsberg’s photos are among the wide variety of materials researchers regularly request from the Allen Ginsberg Papers, which Robert Trujillo, the head of Special Collections, said is one of the most heavily used collections at Stanford.

The collection includes 600 of Ginsberg’s personal journals, which he started writing when he was 10 years old. There are also tens of thousands of letters between Ginsberg and other writers, manuscripts of everything Ginsberg wrote in his life and a mimeographed master copy of Ginsberg’s most famous poem, Howl.

A diary, open to an entry that Ginsberg wrote when he was 12 years old, saying that he was the “smallest boy in his class,” was among the items Trujillo put on display at Morgan’s talk.

Speaking to the importance of preservation, Trujillo said that “nothing can really replace the value of discovering things about Ginsberg just through serendipity and browsing through correspondence, journals, photographs and drafts of poetry.”

Special Collections librarian Mattie Taormina fields all requests for access to the collection and said its versatility makes it ideal for teaching a range of topics.

“The types of requests we receive for Ginsberg range from a freshman doing a paper on the Beat Poets to the published scholar doing research for his/her next book on Jack Kerouac,” she said. Documentary producers also are frequent users of the materials.

Taormina especially remembered a patron who came in to see the original Howl manuscript.

“He sat quietly in the back and when I walked the room I noticed that he was quietly weeping.” That kind of response, she said, “is not common in our reading room and I will most likely always remember it.”

For more news about the humanities at Stanford, visit the Human Experience.