Possessed by Place

Landscape and longing are central to Binh Danh's innovative photographs.

Photographer Binh Danh, the son of refugees from Vietnam, has long been fascinated with the interplay of place and personal identity. About three years ago, he felt ready to tackle a landscape which he had dreamed about since he was a California schoolboy: Yosemite National Park.

Danh, MFA ’04, a master of alternative photographic processes, chose one of the first photographic mediums, daguerreotypes, in which to work. “Dags,” as the cognoscenti sometimes call them, entail creating a highly polished silver plate and coating it with iodine vapor to create a light-sensitive surface. The plate is then exposed in a camera and developed with mercury vapor. The process, which yields a useable image only a small percent of the time, is so finicky (and toxic) that it was rarely used outside of studios even in its mid-19th-century heyday. Danh has outfitted a rolling studio in a car that he calls Louie (for the process’s inventor, Louis Daguerre) in which to do the work on scene.

The images, mostly 6 ½ by 8 ½ inches, are one of a kind. They shimmer and dance, coming into view only if seen from a certain angle, and possessing a vividness not matched by other processes.

Danh made many of his images standing where the famous Yosemite photographer Carlton Watkins stood, but Watkins (1829-1916) used a later process called albumen prints. The use of daguerreotypes at Yosemite, possibly for the first time, has allowed Danh to take one of the most photographed places on earth and make something fresh.

Binh Danh

And, perhaps more important for Danh, the plates’ highly reflective surface almost inevitably puts the viewer’s own image in the picture. “I like that viewers see themselves in the daguerreotypes,” Danh says. “It injects an element of identity into the work. The viewer senses himself connected to the landscape.”

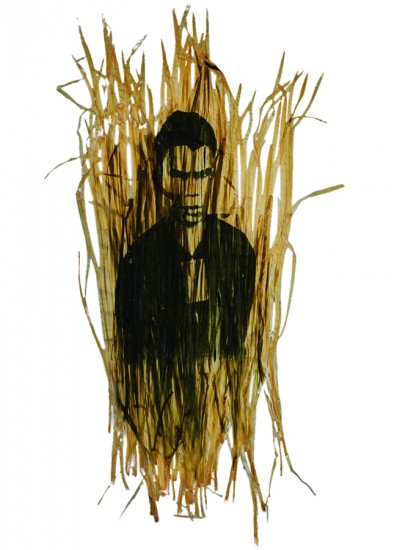

Connection to the landscape has been a perpetual theme for Danh, who first garnered recognition for his work printing images from Vietnam on leaves, in a process he dubbed chlorophyll prints.

For Danh, and other Vietnamese-Americans of a certain age, the Vietnam War is a towering presence and a stubborn void. Danh was only 2 years old when he, his parents and three older siblings fled Ho Chi Minh City in 1979. After time in a refugee camp off the coast of Malaysia, they made their way to San Jose.

The family moved every few years, using their downtown TV repair shop as their permanent address so the children didn’t have to change schools. Danh remembers childhood mostly as work—daydreaming as he swept the shop—but says his family all were grateful to have a roof over their heads. His parents told stories of the old country, and Danh imagined the Vietnamese countryside as a land of abundant fruit trees that he hoped to visit someday.

He daydreamed, too, about the American outdoors. In a visit to a friend’s home, he was struck by pictures of the family’s summer camping trips to Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada. (For Danh’s family, whose only experience of camping was as refugees, it hardly seemed a desirable vacation.) When Danh had a school camping trip in fifth grade, his father bought him his first camera. He was hooked.

It was as a fine arts student at San Jose State University that he developed his technique for developing photographic images on living leaves. The work won Danh a place as one of the youngest artists ever admitted to Stanford’s MFA program, which accepts only five students a year. Danh’s photos have been collected in nearly two dozen museums around the country, including the National Art Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the de Young Museum in San Francisco. Danh, 35, recently took a tenure-track position at Arizona State University’s Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts.

Binh Danh

Danh’s experiments started with his observation that where a garden hose had lain on the grass, the lawn bore a yellow line—where the grass’s photosynthesis had been impeded. He attached film negatives to the broad leaves of a living plant under a plate of glass. Not always, but sometimes, after about two weeks, the leaves would yield a ghostly image. Plucked and placed in a tray, the leaf prints would be preserved with resin.

Danh, too young to remember what refugees call the American War, searched eBay for war-era publications—Life magazines and the like. He photographed images in the magazines to make negatives of hovering helicopters, battlegrounds and war-wearied faces. When transferred to leaves, the eerie, searing images suggested that landscape itself recalled horrors of the war. As Danh, a Buddhist, puts it, “The dead have been incorporated into the landscape . . . during the cycles of birth, life, and death. . . . As matter is neither created nor destroyed, but only transformed, the remnants of the Vietnam and American War live on forever in the Vietnamese landscape.”

Joel Leivick, a professor of photography who advised Danh at Stanford, praises him for taking “a very serious approach to combining his ideas about politics, history and other social concerns and linking them to his remarkable and beautiful and precious objects. It’s very different from what most people are doing.”

Binh Danh

Indeed, one way in which Danh differs from the prevalent contemporary-art sensibility is that his work is irony-free. In the chlorophyll-print project “Ancestral Altars” and the daguerreotype project “In the Eclipse of Angkor,” Danh portrays some of the 2 million people whom the Khmer Rouge killed in Cambodia. “The Crosses” is a collection of daguerreotypes of a hillside in Lafayette, Calif., where local residents have placed a white cross for each of the United States soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. When he was there in April 2012, the total had reached 6,436 soldiers.

But Danh is moving on. The Yosemite work, exhibited last year at the Haines Gallery in San Francisco, is just one example. Starting in 2009, he began photographing American Civil War battlefields using yet another long-discarded process called cyanotype. The process, created in 1842, not long after the invention of photography itself, yields brilliant blue (cyan) images. Danh also plans to visit other national parks to continue the work he began at Yosemite.

But in fundamental ways, his work remains grounded in the musings of that kid in the television repair shop. “My work is driven by an idea and part of that idea is always about identity,” Danh says. “Most of the questions are the ones I started asking as a kid.”