Joe Slusky, "Sitting Bull"

Joe Slusky, "Sitting Bull"

A trio of Stanford Art Spaces exhibitions

Advanced Geometry: Katie Hawkinson, Joe Slusky and Stephen Wilmoth

Stanford Art Spaces is pleased to announce its November-December 2014 art exhibitions: Elementals, oil paintings by Katie Hawkinson; Steel Dreams, painted, welded sculptures, along with drawings and collages, by Joe Slusky; and Sacred Geometry, paintings of geometric polyhedrons by Stephen Wilmoth. Hawkinson (who, incidentally, teaches at Stanford Continuing Studies) and Slusky are a well-known Berkeley artist couple; Slusky and Wilmoth were friends in Berkeley in the ’60s. This is the first time all three have shown artwork together.

Abstract art began in the late 19th century when avant-garde artists, having gradually liberated themselves from realism through various revolutionary styles, took the final step of rejecting visible reality, the mainstay of European art for 500 years. Instead of producing impeccable illusions, they would make visible the realities behind the world of appearances. This mystical element is usually not discussed by the art world, but the circle, square and cylinder that Paul Cézanne discerned in nature (and advised other artists to perceive) became, for some, metaphysical symbols: pure, logical, intellectual constructions, which, they believed, would help humanity become both more rational and spiritual. Although abstraction did not succeed in remaking us, it has proven to be as rich a tradition as representation. These three artists work abstractly in different yet complementary ways.

Hawkinson

In Elementals, Hawkinson is showing paintings from several series executed during the past six years. Her 2008 Swedish Forest paintings are distillations of a family visit there; the vertical stripes set atop horizontal planes and a cool palette of luminous blues and greens easily suggest the birch and beech trees of the north. A 2011 series, Light and the Geometry of Flowers, combines the artist’s interest in light and color (and the colorist Josef Albers), in mandala meditation images, and those slow explosions of color we call flowers. Hawkinson: “the most basic distillation of the geometry within flowers is a series of concentric circles.” These minimalist target- or roundel-format works suggest more than meets the eye, however. If not mystical per se, they are certainly allusive: Foghorn, for example, depicts sound waves; it’s a quietist version of the Futurist painter and musician Luigi Russolo’s 1911 pull-out-the-stops painting, Music. In 2012, Hawkinson visited Norway, “traveling up the fjords into the Arctic Circle in mid-June with endless light, water, beautiful landscape, and time outside of time.” Working more intuitively, with free-form brushstrokes and organic shapes, she created three Geirangerfjord landscapes. 2013 saw the emergence of mythic or cosmogony-themed works like Deliquescent (or liquefying), and Anemochory (seed dispersal by wind), kaleidoscopic vortices of figure eights or infinity symbols seen in exaggerated perspective, as if enveloping the viewer; and the Seed to Dispersal series, with oval, egg and teardrop shapes pulsing across the micro- or macrocosms of Seed, Water Element and Initial Light. This year Hawkinson, intrigued by the competition for dominance between graffitists and their censors, began to see her own work as a conflict or dialogue between competing impulses. Hawkinson: “Making graffiti is akin to drawing and doodling and suggests language, thoughts. The painting over is more about color and form.” These paintings, Energy Centers, Astral Influences, Maelstrom and Fluvial, are complex interweavings of sinuous baroque line (the spiral swirls borrowed from Japanese woodcuts) and saturated color, and they depict, like the Indian miniatures and Russian icons that inspired them, a world in perpetual flux – purposeful, though, even if the meaning eludes us, caught up in the elemental whirlwind.

Slusky

Steel Dreams features eight painted sculptures that derive from the abstract painting pioneered by Wassily Kandinsky and the welded–metal tradition begun by Julio Gonzalez. They have a host of other influences, though, including the car culture of Southern California, where the artist grew up, and “metal, dinky toy cars, military vehicles, and British hand-painted lead soldiers.” Slusky scavenges scrap metal and combines the pieces without sketches or preconceptions, open to improvisation and inspiration: “The sculptures are an exploration of the subconscious, the infinite interior. My work is a depiction, delineation or mapping of this interior universe. Within us, structures exist, waiting to be excavated and revealed. The sculptures are like fossils – the imagination fossilized … The titles of the pieces, many of which come from geographical place names, reflect the belief that each work is symbolic of a new place traveled to and discovered.” The spatial dynamism of the complex forms, which seem animated and sentient, is accentuated by the exuberantly complex color patterns that cover every surface. One critic called his work “both monumental and impish”; another said, “The precision of his technique is matched by the hilarity of his compositions.”

Wilmoth

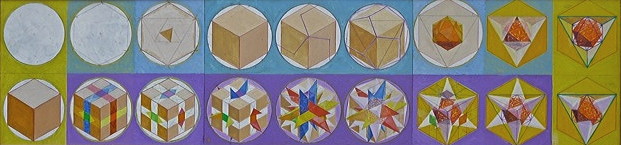

In Secret Geometry, Wilmoth, an architect, presents oil paintings on panel and/or copper depicting crystalline geometric solids, or regular polyhedrons. Wilmoth: “All fits into one. That is: All regular polyhedrons can morph into each other; and, all combined, they form the morphohedron. Most of these paintings are illustrations of this phenomenon, being orthogonal projections along various axes to show how the nine regular polyhedrons (the five Platonic, plus the four Kepler-Poinsot) fit together. Since all these figures grow larger or smaller from each other in the Golden Ratio, similar to the numbers of the one-dimensional Fibonacci sequence, … the morphohedron is [therefore] … the three-dimensional Fibonacci structure.” An animated video created by Wilmoth and Dugan Hammock of these nesting polyhedra is online. It is titled Aleph, after Borges’ story about a point in space containing all other points – in effect, the universe in a grain of sand. Morphohedron, a related video, also by Wilmoth and Hammock, details the mathematical relationships of the nine polyhedra.

Wilmoth’s fascination with this mystical geometry is enlivened with “narrative. Human interest. Optical/visual illusions. 2-D for 3-D confusion. Fun, and, if possible, humor. William Hogarth (1697-1764) has been a strong influence. I believe he was the first Modern artist, and in the 18th century, claimed to have the super-power of ‘wire-frame vision.'”

About SAS

Stanford Art Spaces is an exhibition program serving the Paul G. Allen Building, housing the Center for Integrated Systems, the program’s longtime sponsor, and the David W. Packard Electrical Engineering Building, with smaller venues located throughout campus. All are open during normal weekday business hours. For further information, or to arrange a tour, please contact curator DeWitt Cheng at 650-725-3622 or dewittc@stanford.edu.