In a series of gatherings, Stanford discusses the ethics of wealth

Spread across the school year, a series of talks, readings, films and performances organized by the McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society will explore the relationship between money and humanity.

With all the things that money can buy comes a slew of ethical and moral dilemmas. To name a few: Does wealth make people happy? Are large wealth inequalities damaging to a democracy? What are the moral obligations of the wealthy to those in need?

Throughout the 2012-13 academic year scholars from an array of disciplines will engage the Stanford community in a wide-ranging conversation about the numerous debates surrounding issues of wealth. The series is free and open to the public.

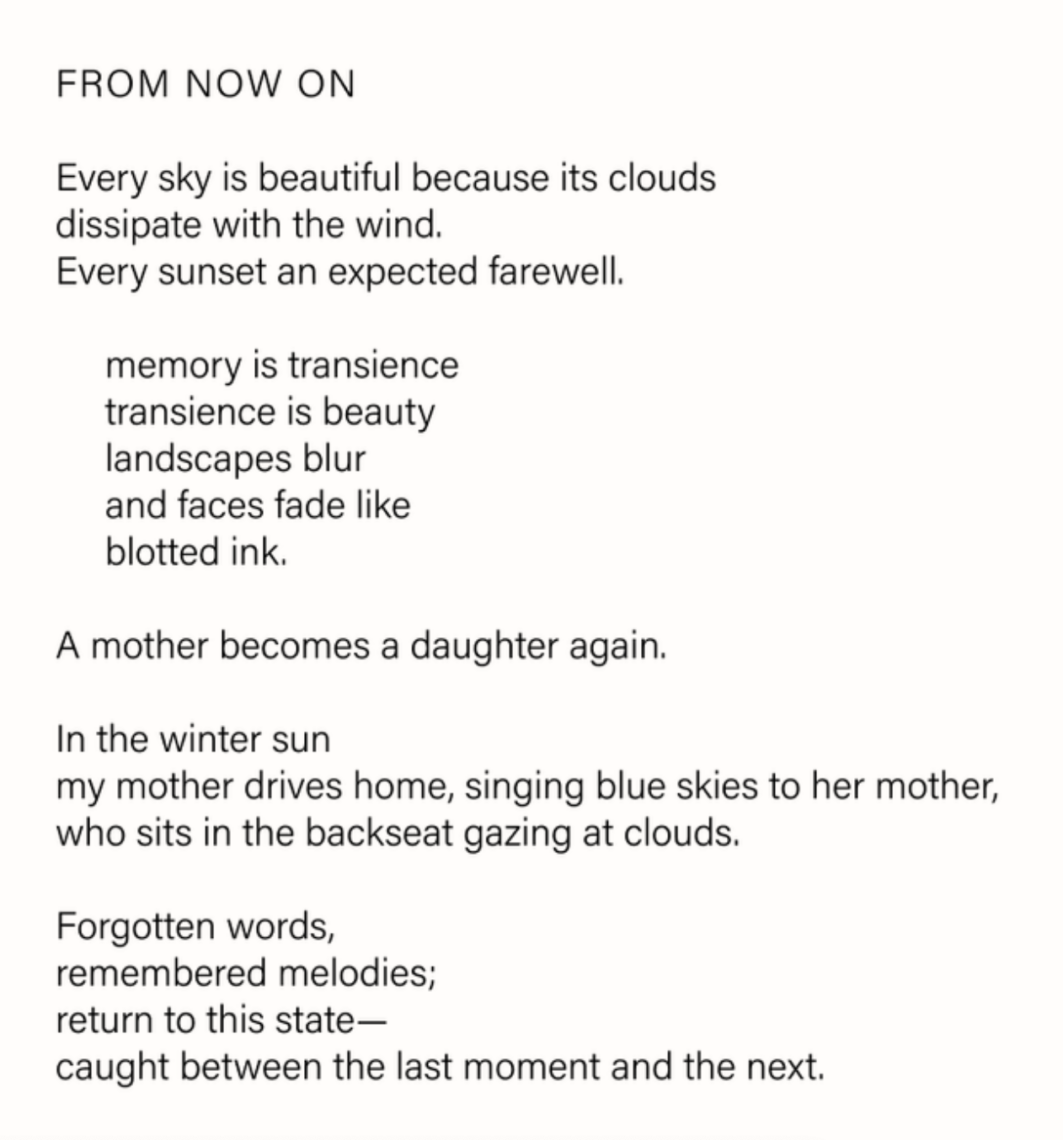

From discussions about spiritual capitalism and income equality to a performance about love and taxes, The Ethics of Wealth events will challenge audiences to move beyond their current assumptions about the production and distribution of wealth.

The series will begin on Tuesday, Oct. 2, with a discussion about wealth in the Gilded Age of America. This period after the Civil War, said presenter Gavin Jones, professor of English, is the first time that the idea of the ethics of wealth emerged in this country “largely because that was the moment when extremes of wealth and poverty became salient.”

Ober said he hopes that discussions will press people to “find better reasons for sticking by their original assumptions about wealth” or that they will “be moved by spirited and reasoned discussion to change their views.”

Organized by the McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society and co-sponsored by several campus partners, the program will highlight the pervasive ethical conundrums that wealth creates in so many facets of modern life, including philanthropy, inheritance, taxation and politics.

Poor or rich, everyone has an opinion about money, but Josiah Ober, professor of political science and of classics who proposed the series theme, said that he wants to “confront people with the fact that their own thinking about wealth is not universal and that others have reasons, good or otherwise, for holding different views.”

Ober said he hopes that discussions will press people to “find better reasons for sticking by their original assumptions about wealth” or that they will “be moved by spirited and reasoned discussion to change their views.”

McCoy Center Director Debra Satz, professor of philosophy, said she expects students to be particularly interested in the topic because they have the most to gain or lose from how society deals with wealth in the future and because undergraduates are “in the midst of deciding what to do with their lives.”

A discussion of the ethics of wealth is particularly timely in light of the global financial troubles and the upcoming election, she said.

The Occupy Movement, Satz pointed out, underscores that “we live in a society where the production and distribution of wealth creates points of conflict.”

A perennial ethical question, Satz said, “is whether you can decrease disparities and still produce wealth.”

It is in the realm of ethics where the humanistic perspective becomes especially valuable.

As Laura Stokes, assistant professor of history, put it, “Ethical dilemmas are fundamentally ambiguous – any apparent conflict of values without ambiguity is scarcely a dilemma.” To find the resolution to these dilemmas, Stokes said, “We should seek the input of scholars who specialize in parsing human ambiguities: humanists.”

In highlighting the value of a historical exploration of the ethics of wealth, Stokes noted that “our modern economic system is a product of history; capitalism was a product of the transformations of early modern Europe.”

In a presentation about money and power in 15th-century Basel, Stokes will examine the ethics of men and women in a time when “the religious-rooted values of an earlier age were in direct conflict with the growing reality of early capitalism.”

It was during the Gilded Age, said Jones, that Americans first found themselves trying to reconcile issues of financial disparity with democratic idealism and egalitarianism. “These questions, which we are still struggling with today, were spawned by the Gilded Age.”

In “Wealth in the Gilded Age: How Much Is Enough?” Jones, the chair of the English Department, will refer to a key literary text to discuss the discomfort caused by the “embarrassment of riches” phenomenon that Americans continue to grapple with.

“Literature,” Jones said, “is a great way to explore, in a kind of real time, the concerns and uneasiness of a society.”

Throughout the ages religion has helped to shape people’s perceptions of the moralistic issues of financial inequalities. Three of the Ethics of Wealth events, including the lecture by Stokes in March, will “address the relationship between individual material prosperity on the one hand and some greater moral or theological good on the other,” said Barbara Pitkin, senior lecturer in religious studies, who coordinated those talks.

“Communities of faith have long and complex histories and varied ways of interacting with the world, including the economic aspect of human life,” Pitkin said. As an example, Pitkin referenced Jesus’ response to a wealthy man who was unwilling to sell his possessions to benefit the poor. Pitkin pointed out that Jesus observed that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God.

“St. Francis of Assisi and the Buddha both turned their backs on family wealth and social prestige to pursue lives of simplicity and poverty, filled with compassion for others,” Pitkin added.

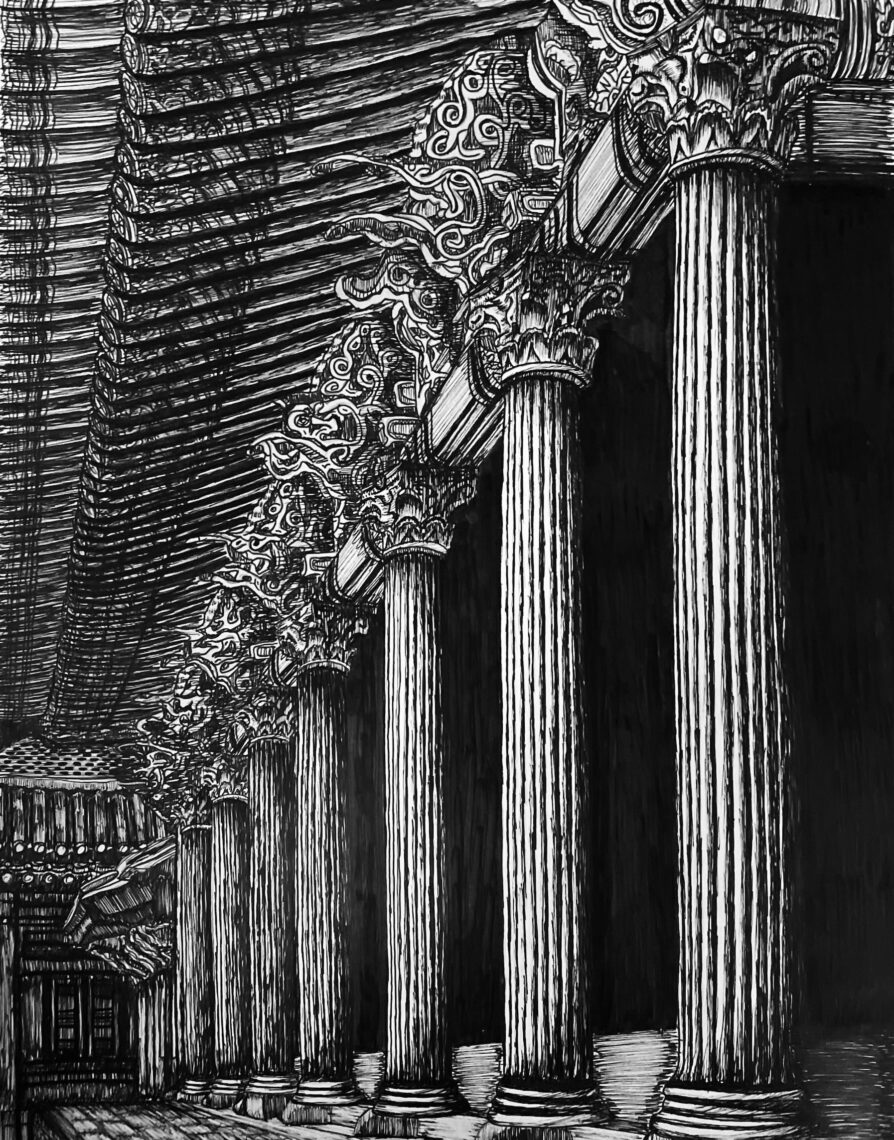

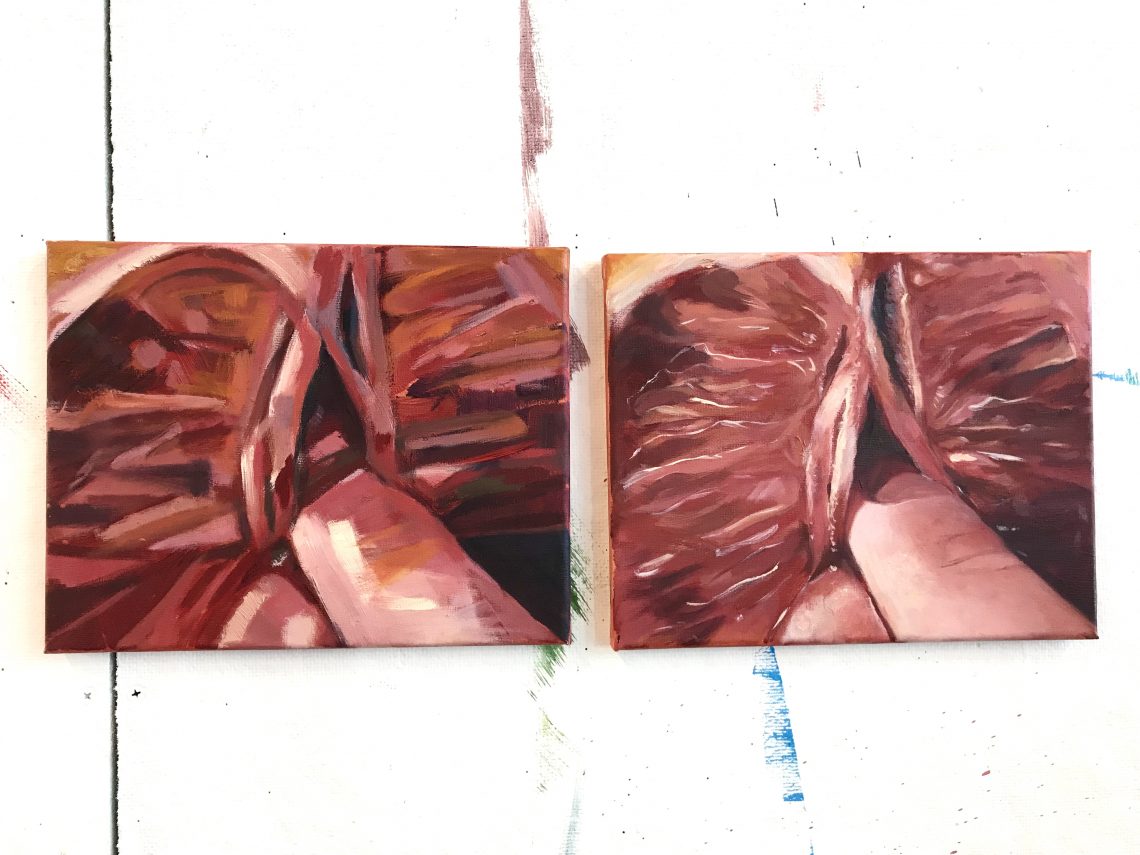

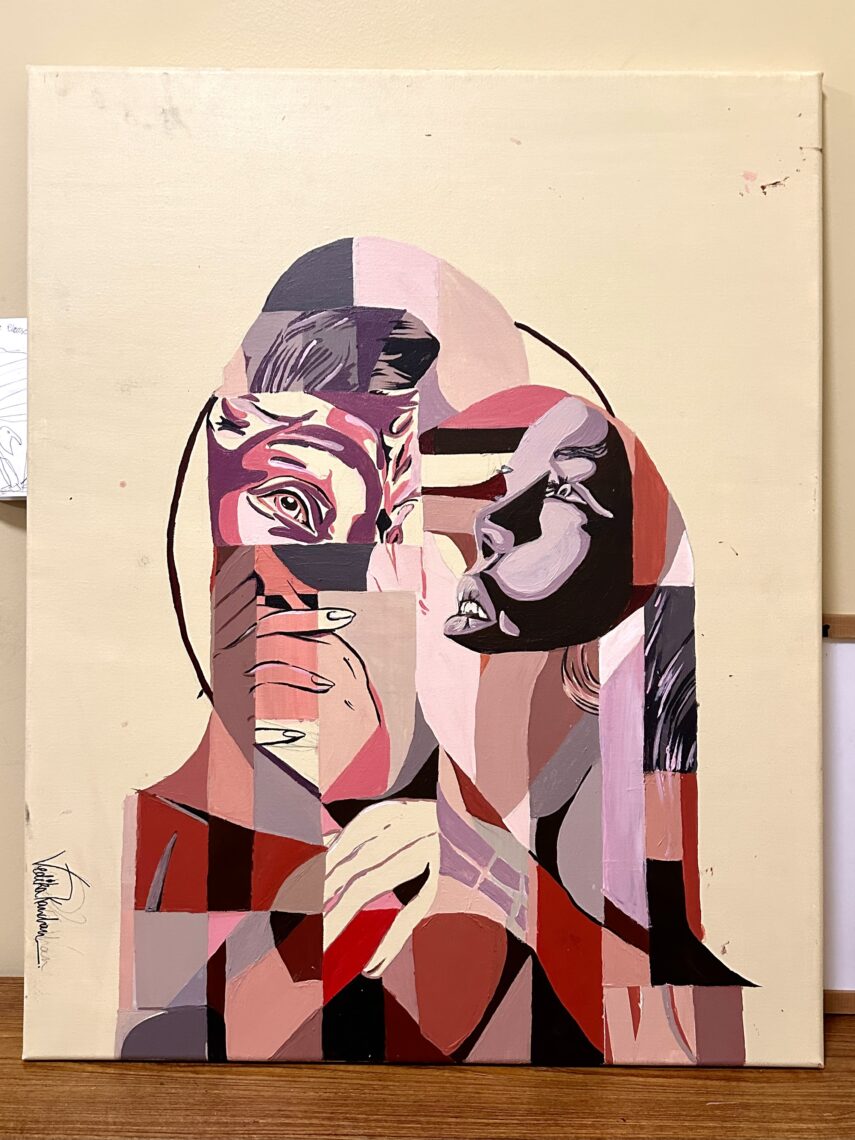

The visual arts will play an important, if unexpected, role in the Ethics of Wealth dialogue. The contemporary art market is sustained by tremendous wealth and “the complicity, whether intentional or not, of academic art historians, galleries, auction houses and museums,” noted Nancy Troy, professor of art and art history.

Troy, who organized the “Contemporary Art in the Museum and the Marketplace” panel discussion scheduled for April 18, 2013, said an understanding of these factors should help Stanford students and people in general to appreciate that idea that works of art “are part of a social nexus that operates in the context of the power and influence that accompanies great wealth.”

Like the previous two McCoy Family Center for Ethics initiatives, the Ethics of Food and the Ethics of War, the Ethics of Wealth will serve as a springboard for developing new research, projects and classes that will continue the conversation on campus and beyond.