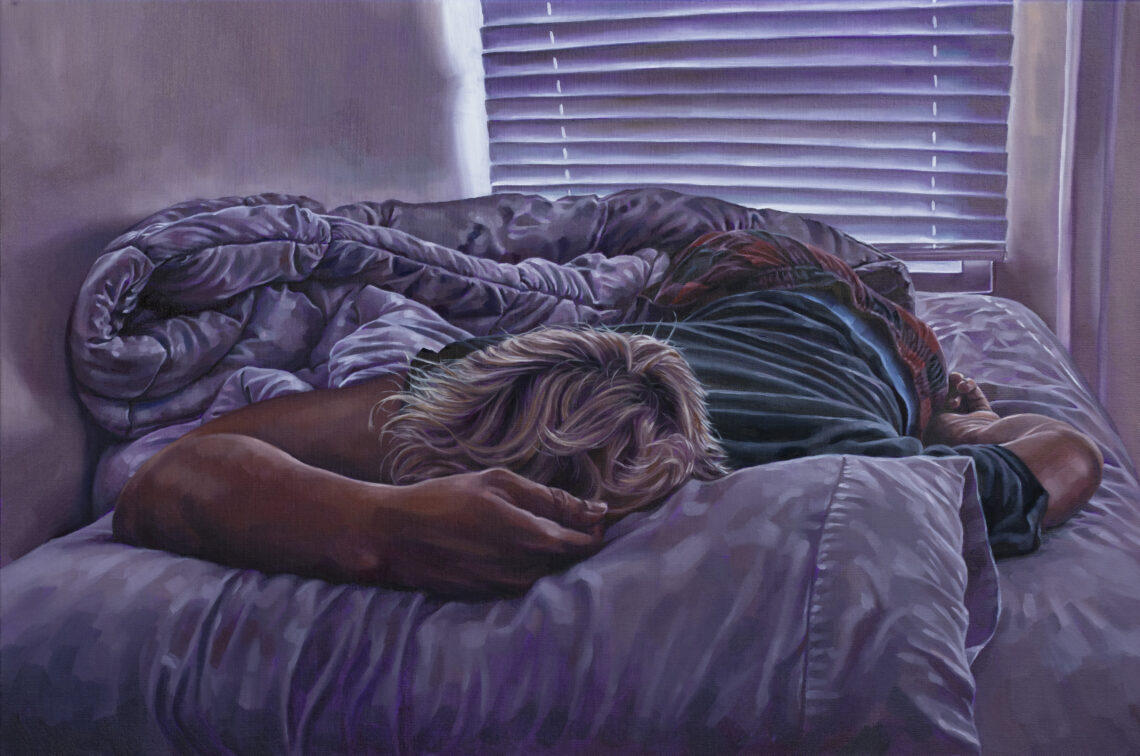

Marci Kwon, Cathy Park Hong, and Jen Liu (left to right) in conversation at the keynote event of Asian American Art Initiative’s IMU UR2 convening. (Photo courtesy of Harrison Truong)

IMU UR2: Asian American Art, Intersectionality, and Collective Memory

A student reflects on Stanford's Asian American Art Initiative's groundbreaking convening that brought together artists, curators, scholars, and students.

Asian American identities have always been in flux. Stanford’s Asian American Art Initiative (AAAI)’s inaugural symposium IMU UR2: Art, Aesthetics and Asian America united artists, activists, and scholars in a multi-disciplinary space for alternative ways of seeing and existing in contemporary Asian America.

Since its conception in 1968 for cross-racial and ethnic solidarity, the “Asian American” label has evolved into a heterogeneous collection of experiences unified by the dynamism of racialization. How do we untangle the shifts in the cultural identities that have led to where we are today? How can art help us revisit the uneven terrains of our collective past?

Launched in 2021, Stanford’s AAAI is providing the space for artists, activists, and scholars to build the ongoing archive of Asian America. The recent IMU UR2 convening was the most recent installment of the AAAI’s ongoing efforts. The two-day convening — held at Stanford Oct. 28-29, 2022, and spearheaded by the initiative’s co-directors Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, Robert M. and Ruth L. Halperin Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Cantor Arts Center, and Marci Kwon, assistant professor of art history — was situated alongside the inaugural exhibitions East of the Pacific: Making Histories of Asian American Art, The Faces of Ruth Asawa, and At Home/On Stage: Asian American Representation in Photography and Film at the Cantor.

Bringing the Cantor together with other campus entities, these interventions document the amorphous and unfolding records of Asian American art through exhibiting historical and contemporary artworks, developing new scholarship on Asian American art history, and connecting art historians from different corners of the world.

“People are working on this material kind of across generations, across different kinds of experiences within the various subject positions that make up Asian America,” said Kwon. “We’re trying to build connections among the people who are engaged in these types of questions or issues; hopefully, new dialogues and collaborations can emerge.”

The panel discussions held in CEMEX Auditorium revolved around the intersectional angles of Asian American art history: Race & Aesthetics, Art Activisms, Global Intimacies, History & Memory, Gender & Sexuality, and Institutional Interventions. The event concluded with the much-anticipated dialogue between Cathy Park Hong, author of the renowned Minor Feelings, and Jen Liu, or Erin — as described in the book — her dissident artist friend from college. The talk spotlighted the value of female friendships, the shortcomings of the 1990s promise of multiculturalism, and the relentless optimism Hong and Liu hold for the future of Asian American arts.

Unlike traditional academic convenings, IMU UR2 attempted to depart from the scholarly structure of authority where speakers assume the role of experts disseminating knowledge to the audience.

“Each speaker was invited to present for 10 minutes about a piece of work that is important to them,” explained Kwon. “The structure of the event was intended to emphasize deep engagement with images and dialogue among scholars in Asian American studies in art history, as well as curators and artists.”

In Race & Aesthetics, art critic John Yau discusses the continued dismissal of race and ethnicity as it is not “a purely formal exploration” of the American art scene during the 1980s. In his essay “Please Wait by the Coatroom” (1988), Yau discusses the Museum of Modern Art’s continued separation between Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and Cuban artist Wifredo Lam’s The Jungle (La Jungla) (1943): both abstract expressionist works, where Picasso appropriated African gods, and Lam reappropriated Picasso’s work and his own culture to restore the gods that were once stolen. Despite his cultural heritage, the descriptions of Lam, cleaved by the detached “standards of objectivity” of critics and curators at the time, appeared like a white artist who followed the footsteps of Picasso.

“Lam was judged to be a derivative white or colorless artist; [MoMA curator William Rubin] considered Lam’s [biracial] identity, which is an amalgamation of Asian, European, and African lineages, irrelevant to his art,” said Yau.

To Yau, the reduction of Lam’s work as a footnote, hung by the coatroom, rather than a conversation, in the broader global developments of art made visible the glass ceiling. To acknowledge this conversation would be to acknowledge the embedded role of racial aesthetics that would throw white artists’ canon into disarray. This institutional failure to represent results in shame and brushing aside history that takes primitivism as mere inspiration but not culture. While MoMA later positioned Lam’s The Jungle (La Jungla) opposite Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, this history highlighted the struggle of past artists and the role of criticism in American history.

Like Yau, Dorothy Wang, professor of American studies at Williams College, highlighted the structural reduction of cultural complexity in Asian American art by discussing Prageeta Sharma’s poem “Grateful.” In it, Sharma discusses the cost of appeasing white love and the potential harm of making legible complicated themes through the limiting vocabulary of the American artistic canon. Wang warns that gratitude does not mean allowing yourself to be a token. “There is [a] huge price to be paid when you want that acceptance from a larger society or critical elite,” said Wang. Instead, Wang argued that we should be grateful for our predecessors: artists, poets, activists, scholars, and forgotten “ordinary” people who made possible the freedom in the artistic tradition of today.

During Global Intimacies, diasporic art unsettled the categories of Asian American art by broadening the veins of national art history. For Patrick Flores, curator and professor of art studies at the University of the Philippines, Asian America may exist as a station in the broader movements of global art history. Flores discussed the life of late Filipino painter Anita Magsaysay-Ho’s egg tempera painting Egg Vendors (1955) to complicate Asian American scholars’ “obsessions” to simplify the transnational decolonial implications of a global web of art history into Asian American art history and its diasporic complement.

With her educational history, from the Philippines to the United States, then a part of the New York art scene, Magsaysay-Ho is part of the American tradition of painting and recognition, identity and, by extension, capital, an inheritance afforded by the privileged exposure to modernism and globality.

However, her stint in the United States exists as a temporary migration; her eventual returns to the Philippines and her naturalized citizenship as Canadian and Brazilian complicate the position of modern globality in piecing together the history of the Asian (American) artist. Flores argued how Asians in America are being quickly welcomed or dismissed by Asian American scholars to create a legible fabric of Asian American ontologies when they might be indicative of the “obsessions” of the current scholarship.

In discussing the late landscape painter Matthew Wong, Winnie Wong, associate professor of rhetoric at UC Berkeley, focused on the artist’s online community and digital bohemia. “Matthew Wong’s life of global intimacy should help us reflect on how and by what means we want to build our communities,” said Wong, concluding how the lineage of influences and developments of contemporary art is more enmeshed in global history than ever before.

Concluding the convening, the conversation between Hong and Liu touched on how by archiving mythologies of friendships, there can be new space for representation. While white male artists have mythologized their friendships, before she wrote Minor Feelings, she did not see a model for archiving her transformative friendships with Liu and another friend, which offered her a place to grow without having to explain herself. By sharing some background, there is some form of kinship. “That’s what I have with Jen … part of that [jeong] is relaxing and not feeling like you have to explain yourself to the white gaze,” said Hong, explaining the Korean word for loyalty and strong emotional connection to people and place.

Reflecting on their college years, Hong and Liu found their mentorship by faculty of color, such as the poet Myung Mi Kim, who instilled in Hong early on the realization that art has been and continues to be political. During the 1990s, both Hong and Lui felt like the multiculturalism movement was on the verge of bursting into the mainstream but fell short. “Obama[’s presidency] was treated as post-race, but then it became exhausted,” reflected Hong. Later, exhibitions for white guilt were awarded as reparation. Despite the shortcomings of the 1990s, they are optimistic about the recent movement in multicultural solidarity today. “It didn’t have the same kind of urgency and upheaval as now,” said Hong. Looking forward to better representation in the future, Liu posed a critical open question: “How do we continue the momentum without needing another moment that calls into question the relevance of Asian American labeling?”

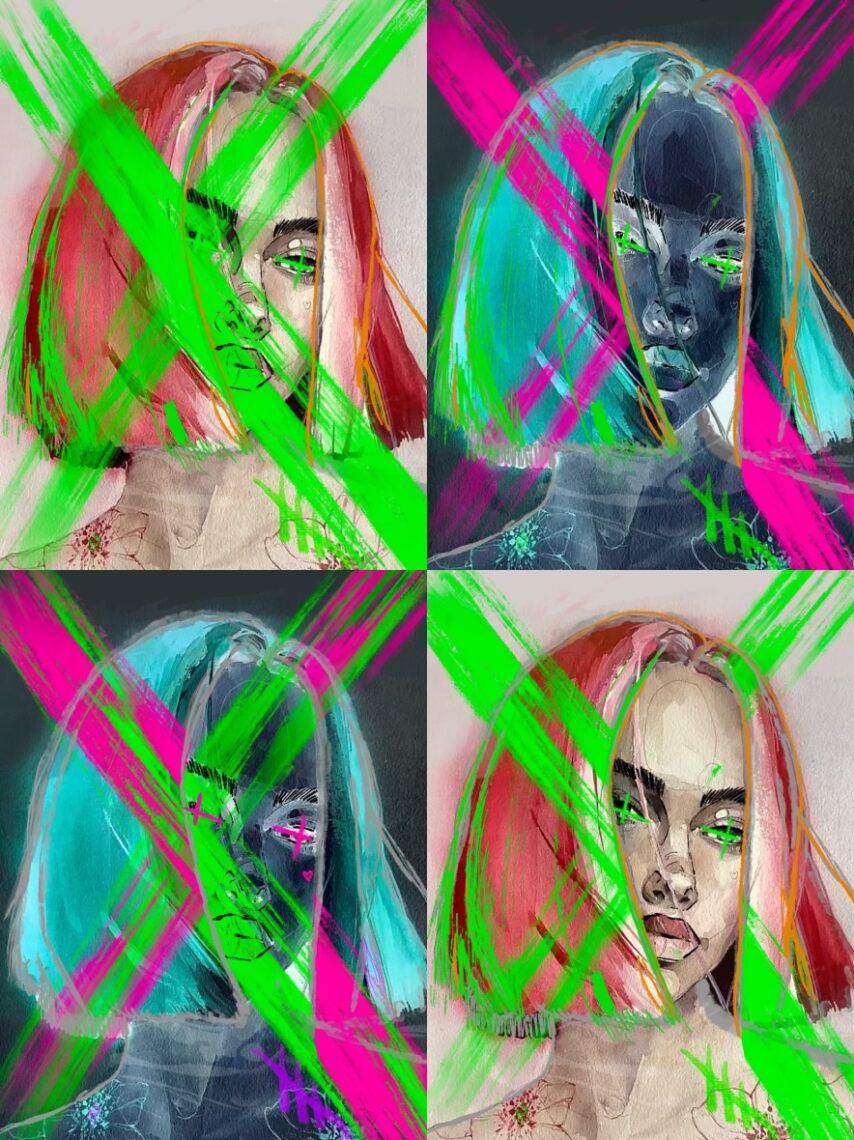

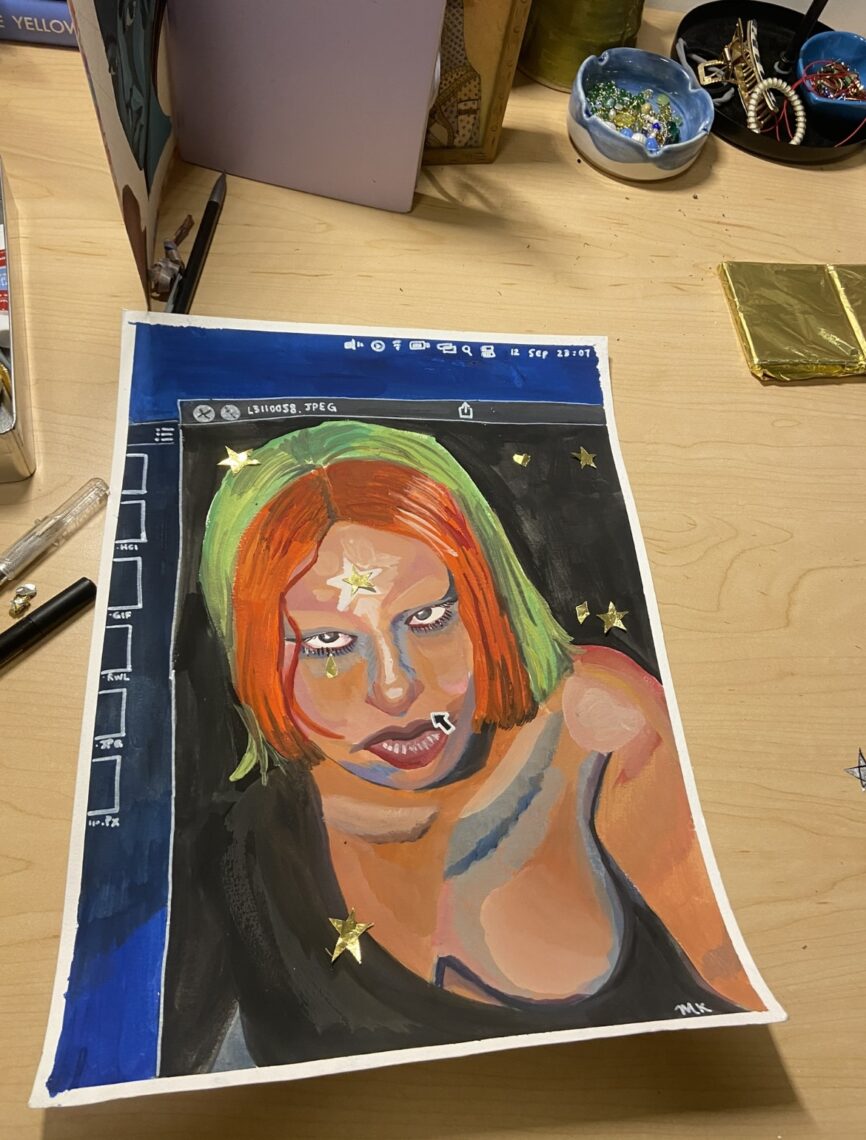

Performance lectures by Việt Lê, associate professor of art at California College of the Arts and Stanford CCSRE Mellon Fellow, and works by artist Catalina Ouyang in the Gender & Sexuality panel engaged the audience in non-linear ways of thinking about the intersectionality within the shifting fabric of the Asian American term, while panel discussions in Institutional Interventions moderated by Alexander shed light on pedagogical, scholarly, and curatorial approaches to ensure longevity in the Asian American art canon.

The public panels of IMU UR2 are situated in the larger efforts by the AAAI to incubate more scholarly work. Prior to the public panels, scholars Mark Dean Johnson, Yinshi Lerman-Tan, and Susette Min presented original research on works in Cantor’s exhibition East of the Pacific, curated by Alexander, during a private study day. Other AAAI exhibitions on view at the Cantor were The Faces of Ruth Asawa and At Home/On Stage: Asian American Representation in Photography and Film, curated by Maggie Dethloff, assistant curator of photography and new media.

Despite its futuristic title, IMU UR2 references the legacy of Chinese-American painter Martin Wong’s painting IMU UR2 (1973) and his malleable, multifaceted, and multicultural career that spanned multiple decades and grappled with early modern Asian American art. Furthermore, Wong’s queerness positions him as a nexus, a connector across various lineages of artists often left out of the Euro-American canon. Martin Wong’s catalogue raisonné at the Stanford Libraries was also launched during the convening, open to the public for research and exploration. Artist Danh Vo later adopted the title in his 2012 installation of Wong’s objects in the home that he shared with his mother. For Kwon, the traditions of archiving in the title IMU UR2 represent “the cross-generational relationships among artists, families, and subject positions.”

By bringing together the many corners of contemporary Asian American art, the convening becomes a part of the AAAI’s mission to foster precisely this momentum: because “I am you, you are to/too/two.” The various ways of examining the subject of Asian American identities and art and cultural production that emerged from the symposium remind us that the self is not singular. Instead, like the title of the convening, the ongoing stories at the crossroads of art, identity, and collective memory are made in relation to others, who are likewise made in relation to us.