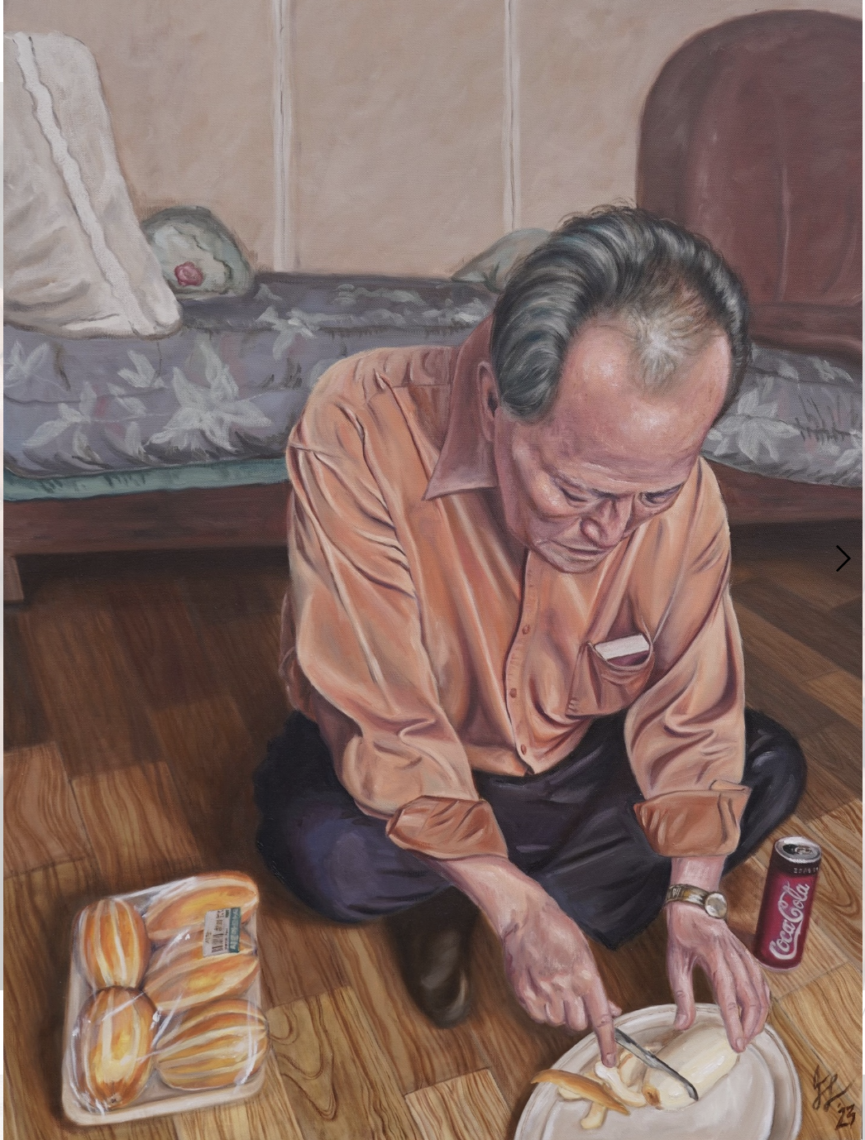

Linda Cicero

Linda Cicero

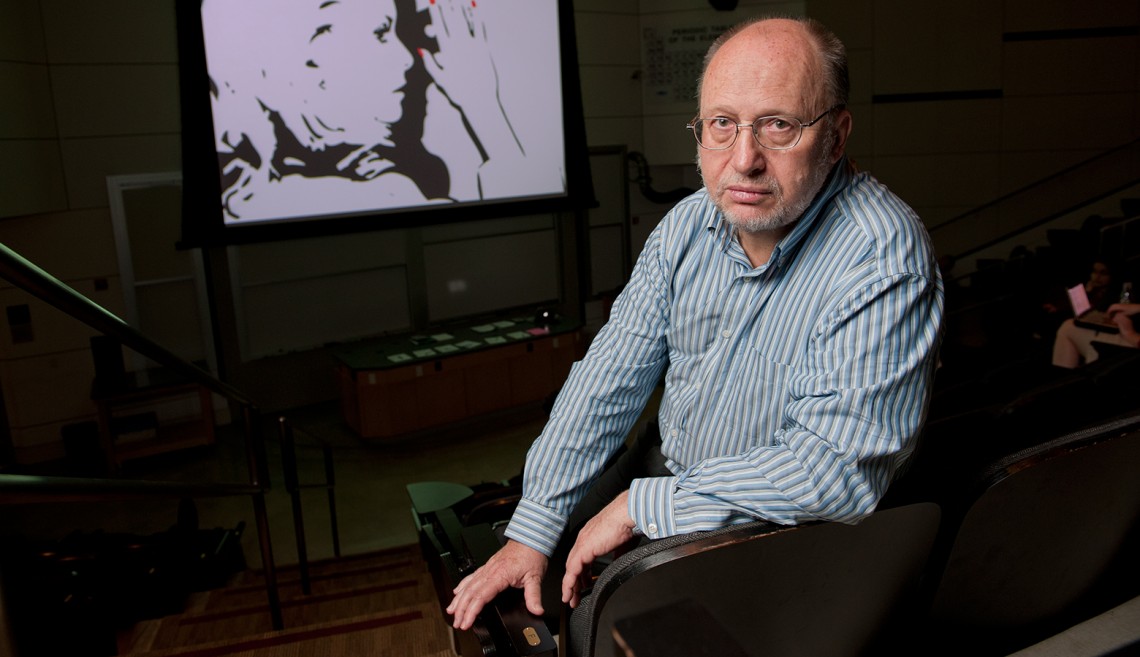

Stanford’s Apostolidès teaches his gender studies/French film class for the last time

After 20 years of teaching Stanford students to learn by watching how women are portrayed in French cinema, Professor Jean-Marie Apostolidès has taught the class for the last time. He'll be working on a book about the way images have come to dominate society.

With a periodic table on the wall and an eyewash faucet next to the door, it’s clear that the William D. Hewitt amphitheater is intended for science. But twice a week during the spring quarter, French Professor Jean-Marie Apostolidès has introduced students to a decidedly different type of experimentation.

Instead of beakers and data tables, Apostolidès uses provocative film clips and challenging questions to lead students through engaging thought-experiments.

For the last 20 years, Apostolidès has been challenging undergrads to develop a critical understanding of gender representations through the study of film in a course called Images of Women in French Cinema: 1930-2000.

In a recent class, for example, Apostolidès argued that the notorious film La Femme Nikita is about much more than a femme fatale. Apostolidès pointed out that the characters could only have been conceived in the post-patriarchal system that emerged after the social tumult and sexual revolution that took place in France in 1968.

“It is the story of a male who is trying to transform a woman into an image of what femininity should be,” Apostolidès said.

Apostolidès, whose research is at the crossroads of cinema, theater, social sciences and psychology, is passionate about what stories tell us about our imagination.

While his early scholarly work centered on 17th-century theater and psychology, he has gravitated toward the study of images in film and print (graphic novels) in his more recent pursuits.

He sees cinema as a portal into the complexities of art and narration. An analysis of the history of France “through the role of women in narrative is like taking an X-ray of the country and its social issues,” said Apostolidès.

Over the years, students have enrolled in the class expecting that it would be entertaining but not necessarily enlightening. However, they typically found that after a couple of classes, they were taking part in heated discussions about things like social norms and the role of narrative.

“It looked like a fun [class] that dealt with film while also satisfying a general requirement, so I gave it a shot,” said freshman Henry Trione.

A different way to watch film

The class helped him appreciate the meaning of “the camera’s gaze,” or where it wants you to look.

“Usually, we just stare blankly at the screen and absorb what’s going on,” Trione said. “Whereas in reality, you can better understand a film by entering into the motivations the director.”

The broad appeal of the film medium offered an accessible starting point for students coming from any discipline to study issues relating to gender.

Sociology major Jasmine Rodriguez went into the class wondering how serious the material would be, but soon discovered that Apostolidès’ perspective and engaging lectures pushed the students “to challenge our preconceived notions.”

In particular, as a female student she initially found it disturbing to see the extent to which women can be fetishized in films with something so subtle as camera perspective.

“At the same time,” Rodriguez said, “it’s nice to see how certain stars like Brigitte Bardot own their sexuality and use it to exercise influence on men. It’s actually kind of empowering.”

Economics major Nathan Nolop said that Apostolidès has “helped us look deeper into the film and [to consider] what’s not shown.”

For Nolop, the humanistic approach has given him “a whole new perspective for what the director is doing and how we can interpret the characters, which is totally different from having [economics] equations and reapplying them.”

The class also has helped Apostolidès develop his research. Apostolidès said for his book, he will expand his research beyond French representations of gender to a general theory of image in cinema.

He described the research endeavor as “an attempt to understand how society is in a state of complete metamorphosis through the multiplication of images. We have gone from a society of representation to one of simulation, and the image is the currency in this transformation.”

Apostolidès said that the social importance of cinema supports this theory.

“Since the 18th century, the possibilities for an adventurous life have basically disappeared,” he said. “And yet, adventure is as necessary for human life as water, bread or sex.”

Fiction, Apostolidès maintains, has allowed us to compensate for a lack of adventure in our lives.

“First it was the [serialized] novel, where there was a new episode of a greater adventure was published in the newspaper every week,” he said.

A sense of adventure

Cinema built upon this thirst for vicarious adventure because “of the sense of adventure that it offered. It transformed how we feel, love and imagine,” Apostolidès said.

The visual quality of this form of storytelling has made the medium much more powerful than novels, he said, and suggests an economy that is at the heart of Apostolidès’ theory.

“Images are produced, exchanged and circulated in what I call the iconomy,” he said.

“Iconomy,” Apostolidès said, is a term that refers to a new field of knowledge: the study of images, considered for their general function, rather than that of individual images that are autonomous from one another.

Because images allow us to exchange ideas like money allows us to exchange goods, “we cannot exchange emotions without images.” He argues that images are as important to how we conduct our lives as they are to the formation of our imagination.

This spring, Apostolidès taught Images of Women in French Cinema: 1930-2000 for the last time. He will now focus on his book project.

Apostolidès has written all of his previous publications in his native language of French. But because the class has influenced so many Stanford students over the years, he has been inspired to write this book in English.

“I think this class, and the theory that I have developed through it, will be that major work that I’ve always wanted to write as my most original theoretical contribution to humanities research,” Apostolidès said.