-

Stanford University Libraries. (Photo: Colin Reeves-Fortney/Stanford Online)

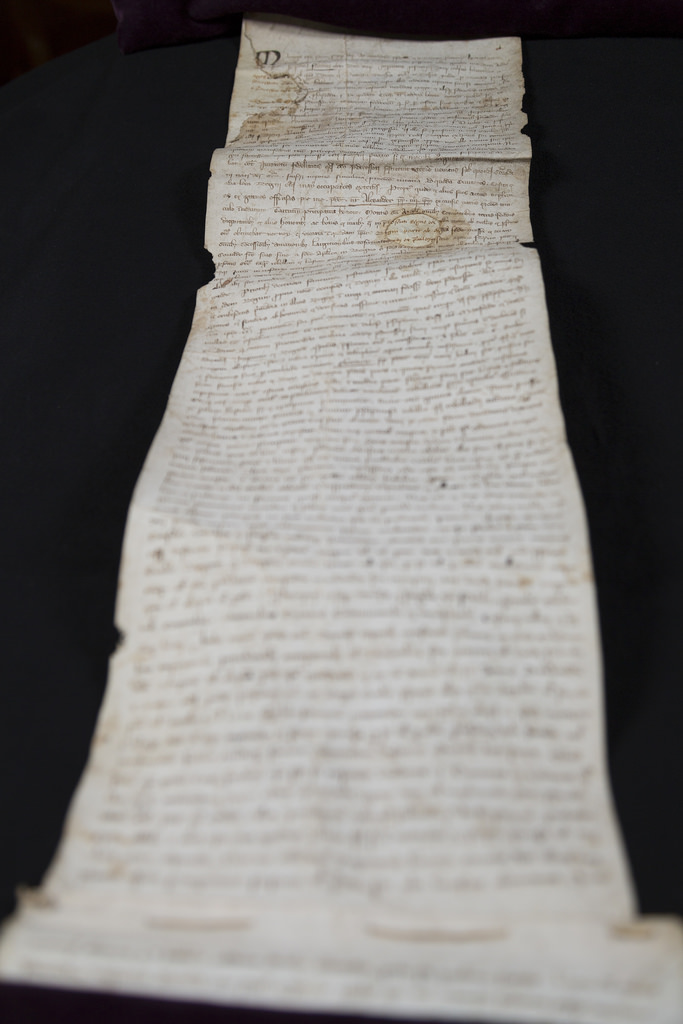

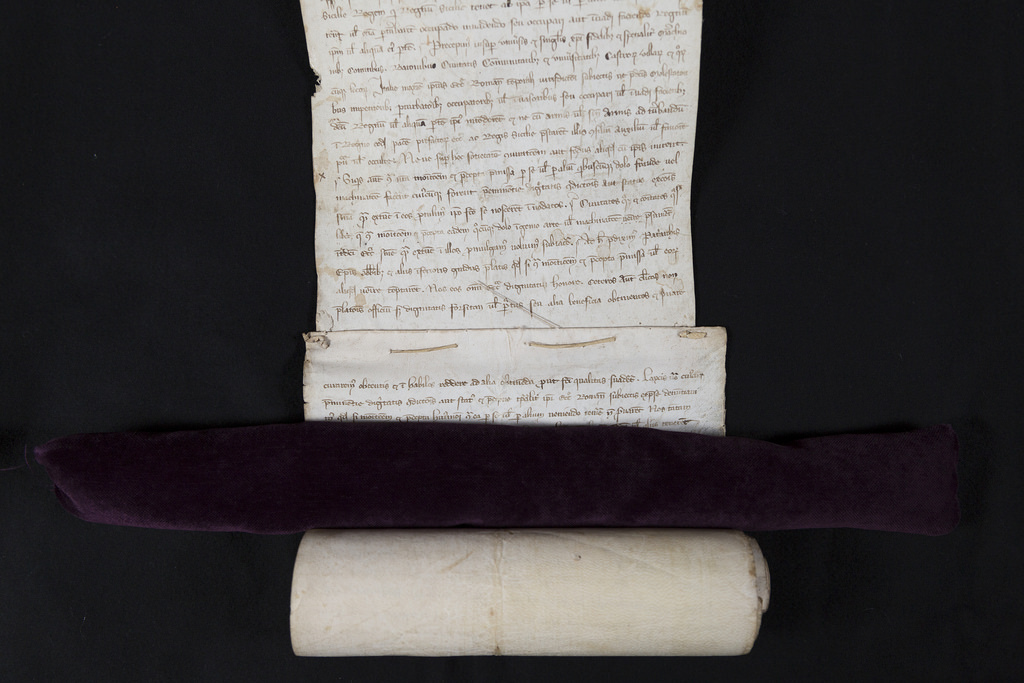

Side view of a scroll containing the particulars of the papal chancery's threat of excommunication of King Peter III of Aragon and the Emperor of Byzantium, Michael VIII Palaeologos. On vellum. Circa 1281. -

Stanford University Libraries. (Photo: Colin Reeves-Fortney/Stanford Online)

Showing the text of the scroll issued by the papal chancery. -

Stanford University Libraries. (Photo: Colin Reeves-Fortney/Stanford Online)

Showing the simple sewing used to connect separate pieces of vellum to form the scroll. -

Stanford University Libraries. (Photo: Colin Reeves-Fortney/Stanford Online)

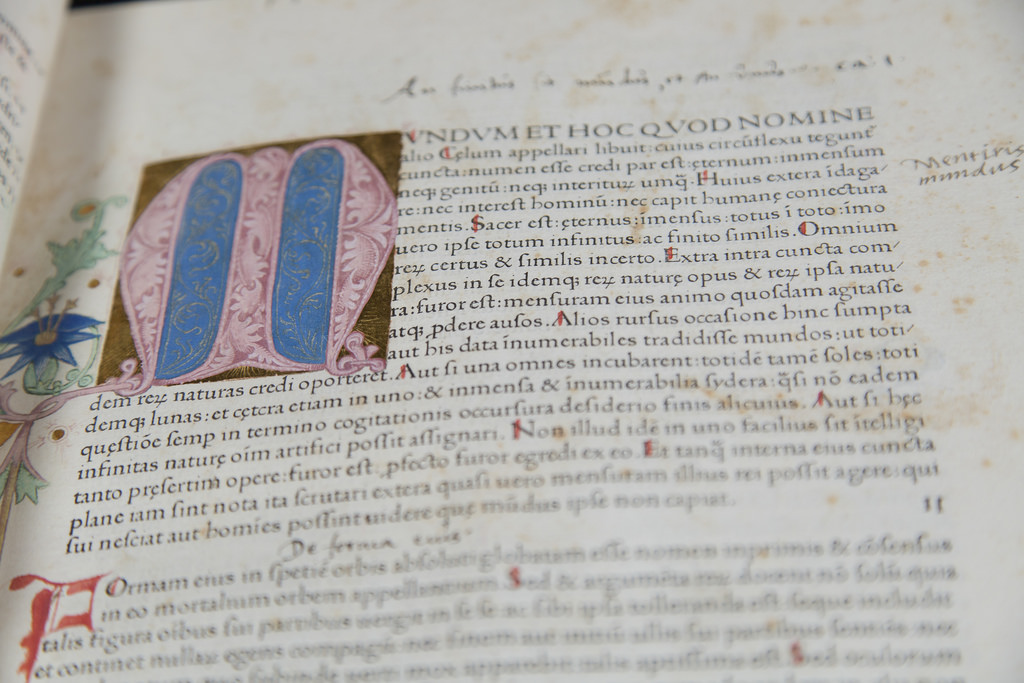

Illuminated initial and decoration in the margin of the first printed edition of Pliny’s Natural History, Venice, 1469. -

Stanford University Libraries. (Photo: Colin Reeves-Fortney/Stanford Online)

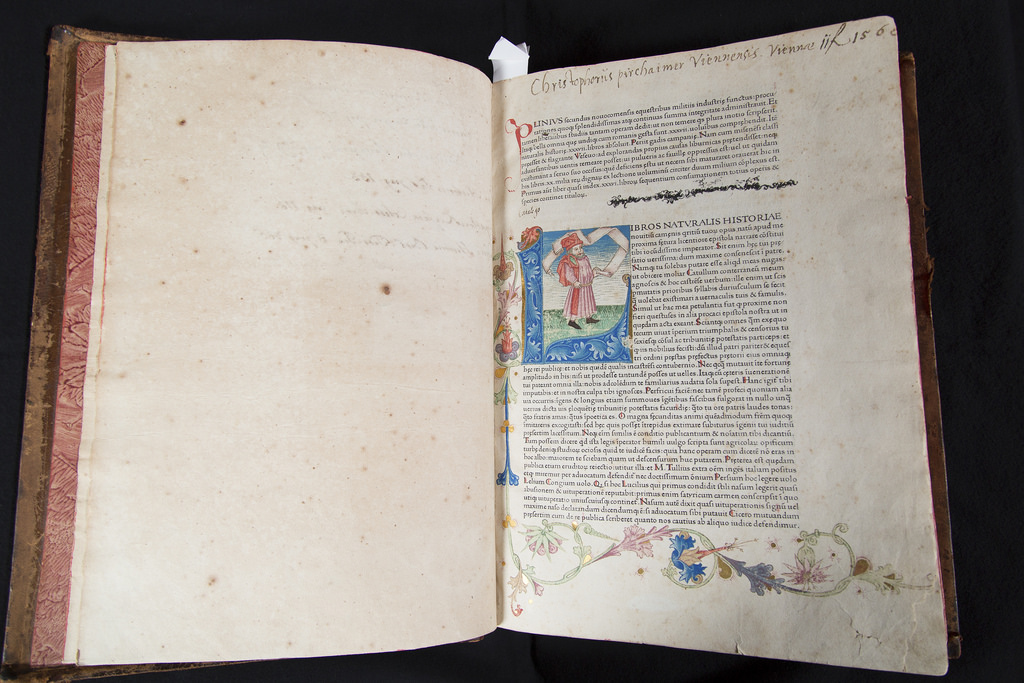

Opening page of the 1469 Pliny. -

Stanford University Libraries. (Photo: Colin Reeves-Fortney/Stanford Online)

Binding of the 1469 Pliny. -

Stanford University Libraries. (Photo: Colin Reeves-Fortney/Stanford Online)

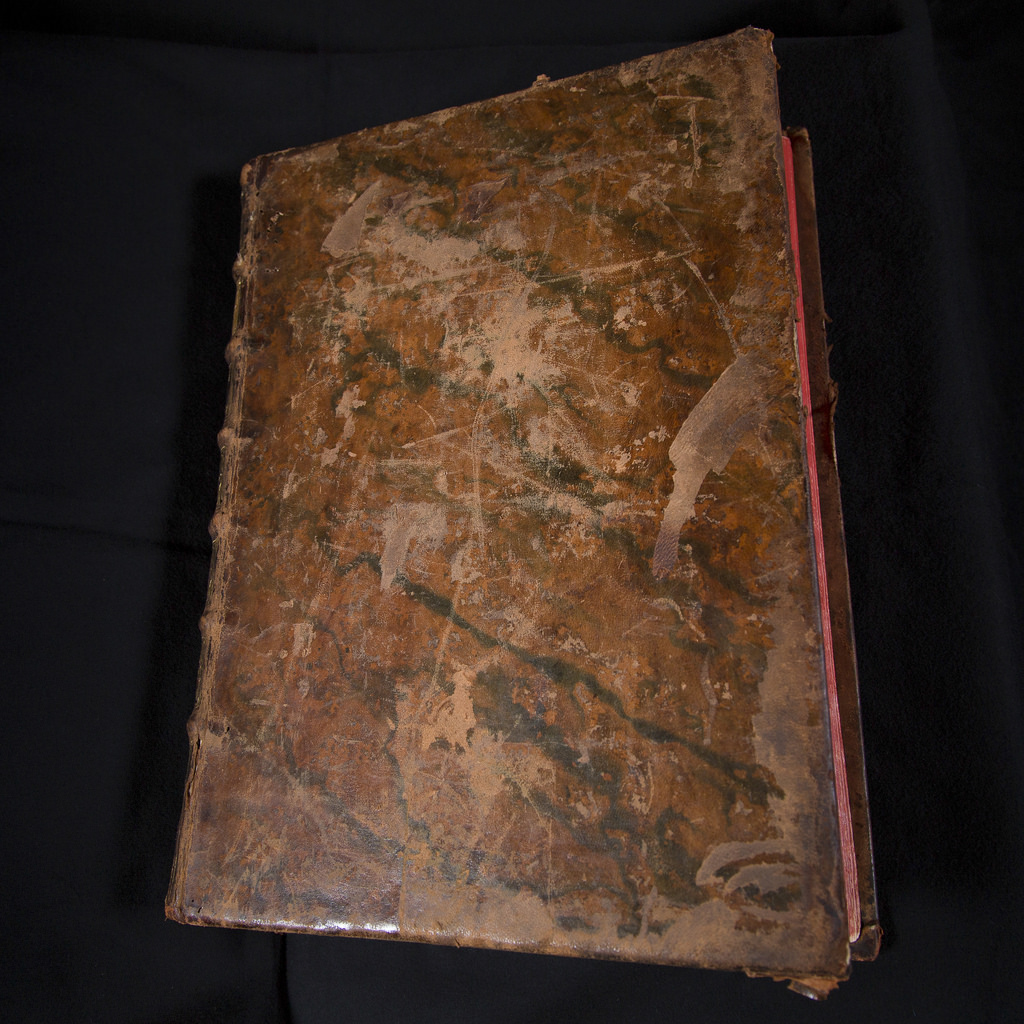

From a manuscript known as the Prayerbook of Elizabeth of York, wife of King Henry VII of England. Traditionally held to have been owned by Elizabeth as well as her mother, Elizabeth Woodville, wife of King Edward IV of England. Early 13th century. On vellum. -

Stanford University Libraries. (Photo: Colin Reeves-Fortney/Stanford Online)

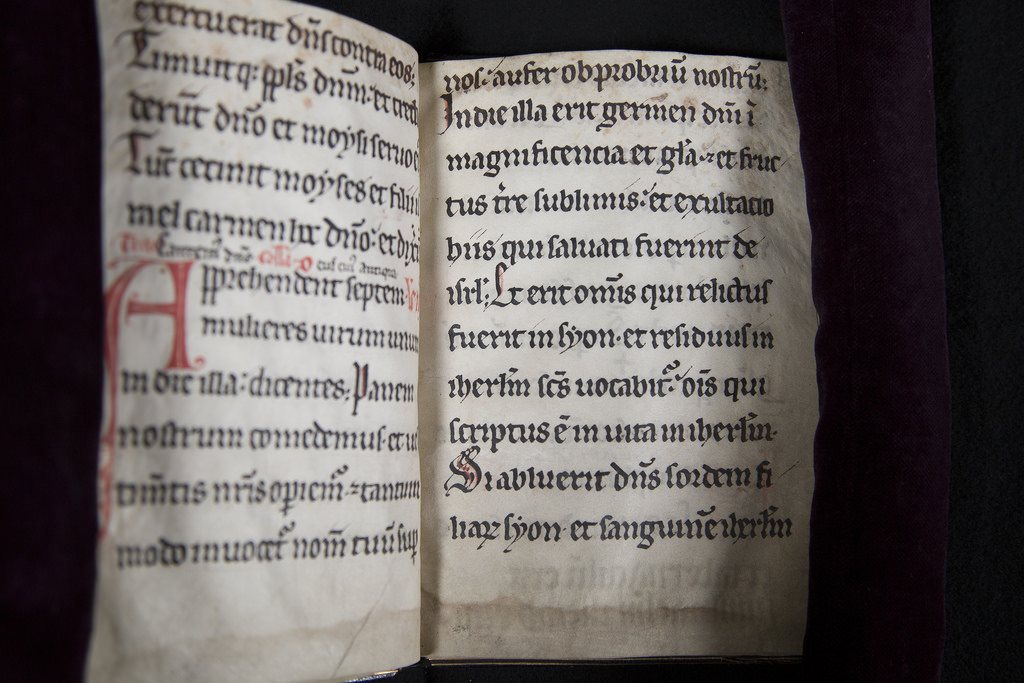

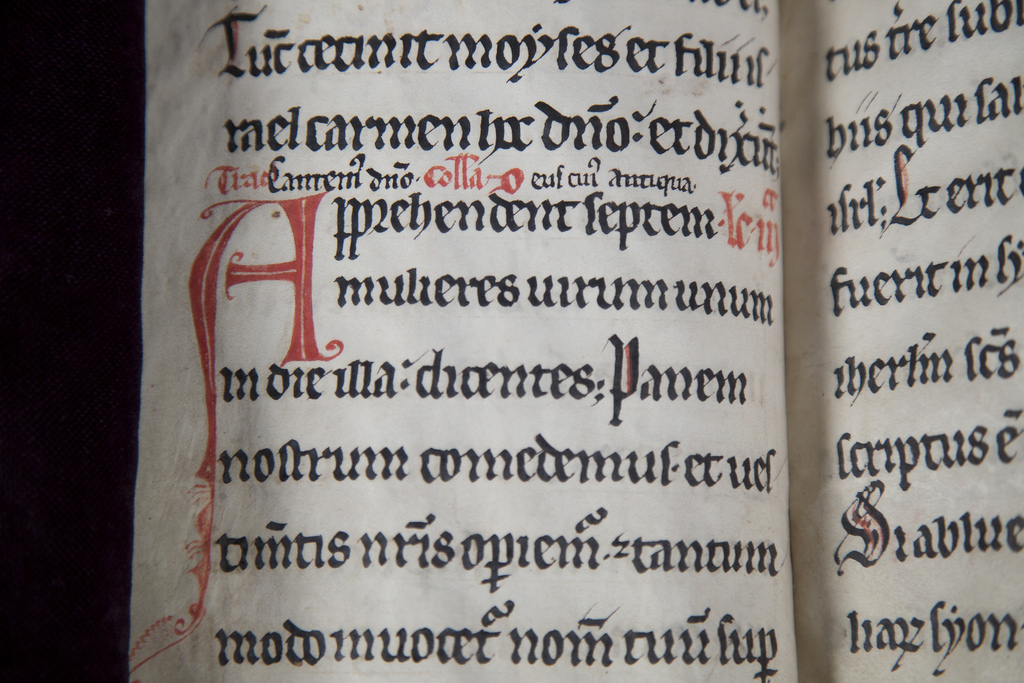

An opening in the prayer book of Elizabeth of York. -

Stanford University Libraries. (Photo: Colin Reeves-Fortney/Stanford Online)

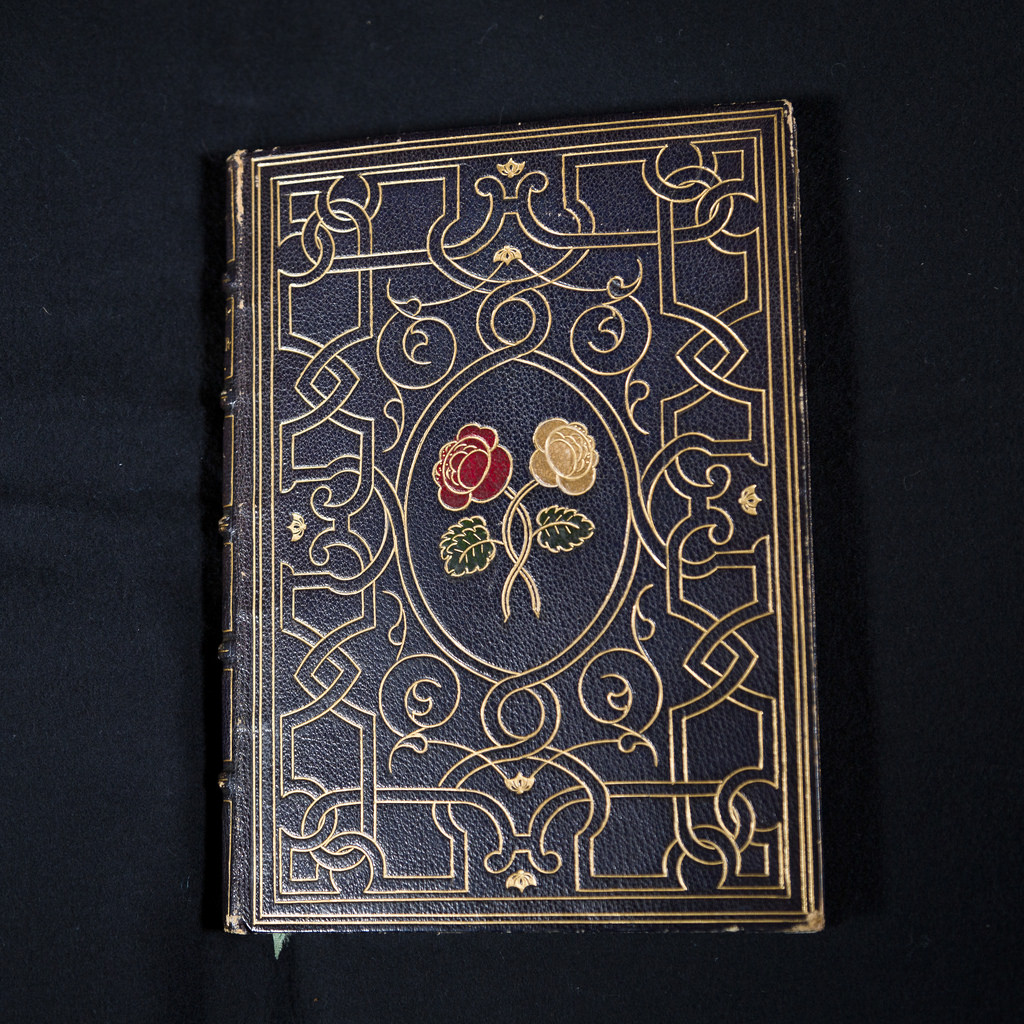

Prayer book of Elizabeth of York, with 19th-century binding of ornamental morocco.

In her research and in a new online course, Stanford scholar delves into the secrets of medieval texts

Digital tools, including a free, public online manuscript training course, are allowing English professor and medieval manuscript scholar Elaine Treharne to share her expertise well beyond traditional classroom walls.

Most people don’t realize that medieval manuscripts carry in them not only the words of people centuries ago, but also a history in blood, sweat and tears – quite literally.

Take the 13th-century British tome that did double duty as an impromptu shield for a hapless monk when the Vikings attacked his monastery. Bloodstains that can still be found on its interior pages bespeak of the gruesome encounter.

Or witness the telltale signs of devotional weeping – blurry ink and puckered vellum – that pepper descriptions of the suffering of Christ in numerous illuminated prayer books once pored over by the faithful throughout Europe.

Texts of the Middle Ages may be something of an open book, but, says Stanford medievalist Elaine Treharne, it takes a trained eye to recognize the numerous and nuanced historical details in the manuscripts that once served paupers, priests and princes. But help is on the way, in the way of a Stanford Online course.

Where the first European manuscripts were made, how they were constructed, what they were about and what they reveal about European culture are among the topics Treharne covers in the free course, Digging Deeper: Making Manuscripts.

In over three decades of research, teaching and writing, Treharne, the Roberta Bowman Denning Professor of Humanities at Stanford, has cast her eyes on thousands of codices, scrolls, diplomata and books, from the most gilded and bejeweled to the most simple and modest. She has published dozens of articles and 26 books on Old and Middle English, manuscript studies and, more recently, early text technologies.

“Medieval manuscripts provide us with a real point of access to the Middle Ages. They put us in direct contact with ancestors in a way that helps us understand the past and make connections with the present,” she says.

This online manuscript training course brings rarely seen volumes – generally guarded with great care at Stanford and Cambridge universities – to computer screens worldwide.

With a click of a mouse, amateurs and experts can thumb through texts of epic poems, books of psalms, romances, musical scores, classical manuscripts and more. The works appear in Latin as well as the older varieties of English, French and other European languages. Through video portraiture, course participants can view the manuscripts close up, and can virtually enter the rarefied space of the manuscript repositories and witness how manuscripts are handled.

The hallmark of the course is that it provides the “codes” to the codices. “We help people understand things like how the books are put together,” says Treharne. “Until the 13th and 14th centuries, they were made from various kinds of animal skins, so the pages have a smooth side and a hair side, and analyzing all this is important for learning about the manuscript’s origin.”

Moreover, while it may be fine to glance at a page of vintage Chaucer, unless you’ve been schooled in medieval calligraphy (and Middle English) you might find it difficult to read a word. “Scribes wrote in particular styles of script that can be difficult or impossible to decipher unless you have some instruction,” she says. “This is part of how we help people dig deeper into the works.”

“Each medieval manuscript is made entirely by hand and is therefore completely unique. You never know what you’re going to find when you open one. I’m passionate about them,” says the British-born scholar, who reports finding a particularly delightful treasure on the inner pages of one recently explored tome: a doodle of a sea-monster.

Treharne admits to having an obsession with old texts and their relationship to medieval history since she was young.

“From the earliest age I used to write in notebooks and diaries with locks on them,” she said. “I’ve always been really nosy and like to read what others have written in years gone by. That led to a fascination with the fact that before the printing press, people would go through so much trouble just to produce one book.”

A digital Renaissance

The course – and the expansion of the entire field of medieval manuscript studies – has been made much easier by the presence of the Internet. “Over the last 10 years we’ve seen a large increase in the number of manuscripts now available,” said Treharne, who directs Stanford Text Technologies, a large interdisciplinary project that explores how texts from cuneiform tablets to contemporary books are made.

Currently completing the Oxford Very Short Introduction to Medieval Literature and The Phenomenal Book, 600 to 1200, Treharne also manages a project through the National Endowment for the Humanities called “Global Currents: Cultures of Literary Networks, 1050-1900.” In that project, she says, “We’re analyzing how manuscripts have been constructed all over the world, and we’re training computers how to ‘read’ medieval manuscripts.”

“I’ve had the vision for a course like this for quite some time, but it’s only Stanford’s incredible team of programmers, film producers and digital project managers that has made it come to life,” Treharne says.

The course, which began online Jan. 20, has attracted thousands of course participants from all over the world – and is still open for enrollment. The course modules are hosted on the Stanford OpenEdEx platform and include filmed sequences of experts with manuscripts, reading assignments, a short transcription and self-testing quizzes.

Participants who successfully complete the course can earn a statement of accomplishment.

A second online course, Interpreting Manuscripts, is scheduled for April. “We’ll be looking at the finer business of understanding a manuscript,” Treharne says.

With the advent of the digital age, medieval textual studies will only continue to grow. “There are thousands of manuscripts located all over the world that have never been studied,” she says. “We’ve barely scratched the surface of what’s available.

“It’s an exciting moment in this field. I love it, and I love talking about it. It allows us a window onto the past and gives us insights about who we are as human beings.”

The course received a seed grant from and was produced by the Office of the Vice Provost for Online Learning in collaboration with experts from Cambridge University Library and the University of Cambridge, including Suzanne Paul, the medieval manuscripts specialist at Cambridge University Library; Ben Albritton, a top medieval specialist; and Cambridge University’s Orietta Da Rold, an internationally renowned codicologist and paper specialist.