Stanford dance scholar examines how ballet challenged the Soviet regime

Through a study of one of the most innovative choreographers in Russian history, Stanford Professor Janice Ross discovers how ballet served as a vehicle for political protest in the USSR.

From the royal courts of the Renaissance to modern-day theatres, classical ballet performances have continually delighted audiences.

But in 20th-century Soviet Russia, ballet took on another role, that of a powerful vehicle for political resistance and reform.

Through a study of Russian choreographer Leonid Yakobson (1904-1975), Janice Ross, a professor of theater and performance studies at Stanford, has discovered how Soviet ballet became a deeply politicized art form.

During some of the most repressive decades of Russian history, many of Yakobson’s ballets “celebrated re-invention and self-authorship – the freedom of the individual voice, as subject, practice and medium,” Ross said.

Yakobson, Ross said, “viewed ballet as a vital medium of national identification, important in shaping the contours of Soviet cultural life.”

Drawing from hitherto untapped source materials, Ross found that Yakobson’s productions alternately accommodated and challenged ideas endorsed by the Soviet regime.

The focus of Ross’ current book project, Yakobson created avant-garde ballets that favored idiosyncratic individuals and marginal identity over utopian societies and socialist realism.

Spartacus, which is about a slave who leads an uprising against the Romans, is one of Yakobson’s most enduring ballets. Originally choreographed for the Kirov in 1956, he restaged it for the Bolshoi’s 1962 American tour where it generated diverse political reactions, with Soviets embracing Spartacus as an emblem of Soviet heroism, while Leftist Americans rallied around the Kirk Douglas Spartacus film of the time as a vehicle for defying communism.

Ross offers an alternative reading from Yakobson’s perspective: “One of the subversive, radical things in Spartacus . . . is that he makes it a very intimate, personal tale. At the core of it is a tragic love story about loss and longing.”

A scholar of dance history, Ross first came across Yakobson’s name in scattered references from defecting Russian dancers such as Mikhail Baryshnikov and Natalia Makarova, who praised his artistic innovation.

In 2004 and again in 2012, Ross visited St. Petersburg and Moscow, where she explored Russian archival collections, many of which were not yet indexed or catalogued. She also interviewed many of Yakobson’s former dancers and those who had seen his productions, many of whom had immigrated to Israel following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The key to understanding Yakobson’s personal and professional life was Irina Yakobson, his widow, who gave Ross extant films, photographs, and writings pertaining to her husband’s work. Ross recently donated these items to Stanford University Libraries, which now holds the world’s largest archival collection of film footage and photographs of Yakobson’s ballets.

Performing on a political stage

Yakobson’s appreciation of ballet as a political vehicle was deeply rooted in Russian history. In Russia, ballet’s political aura harkens back to the czars, who first subsidized and institutionalized ballet. Russian ballet cultivated a style that accentuated the disciplined, synchronized movements of a large group of dancers, or corps de ballet. For Ross, this regimented physicality presents to viewers the Russian body politic as an idealized, “many as one” vision of society.

Despite being a product of the imperial age, ballet became an important political tool for the Bolsheviks in the early 20th century. For Vladimir Lenin and his confidants, ballet and cinema comprised the two most important art forms for furthering the revolution. Since dance is nonverbal, it could convey revolutionary messages to the masses more effectively than the written word.

For instance, Tchaikovsky’s ballet Swan Lake premiered in 1895, but, as Ross explains, it later mobilized a decidedly Soviet message: “Within that feminized exterior, is the disciplined body of the military corps, of the army corps. And it’s about order and cohesion and obedience. It’s this sort of imagined community. It’s where nationalism gets performed, again and again.”

Yakobson, Ross recounts, “comes of age through this great, glorious flowering of Russian art in the early part of the 20th century. And he’s there for its being closed down.”

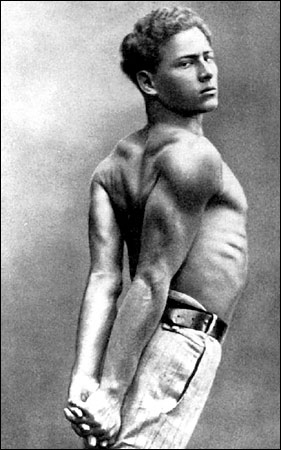

As a young choreographer, Yakobson tried to adapt ballet to Soviet ideals. In the 1920s, he wrote about the need to renovate classical ballet, suggesting that the incorporation of acrobatic and gymnastic movements could help popularize the art form.

Yakobson’s essay “The New Ballet Association,” a dance manifesto of sorts, proclaimed that classical ballet had festered in “artistic stagnation” and “anti-creative quagmire.” Instead, he argued, ballet should modernize to communicate revolutionary thoughts.

But Yakobson was ahead of his time. “A lot of those early experiments fell by the wayside,” Ross says, and comprised “the first acts of censorship against him.”

In his first major ballet, The Golden Age (1930), Yakobson wedded wildly innovative movement to an anti-capitalist statement. Ironically, revolutionaries interpreted this ballet as reveling in the aristocratic decadence it allegedly denounced. Suspecting that Yakobson was nostalgic for the old regime, The Golden Age was promptly censored. This infamous debut colored his entire career.

Dancing on the edge

Growing increasingly skeptical of the revolutionary project, Yakobson struggled to maintain a safe balance between artistic freedom and state censorship. He gravitated toward abstract ballets, a sharp departure from the driving narratives of Soviet ballets.

In contrast to Swan Lake‘s elaborate ensemble work, Yakobson did not choreograph corps de ballet pieces. Instead, he explored how dance could construct a story of the individual and, contrary to the Soviet scheme, the story could end in defeat.

Yakobson’s later works forged new possibilities of movement by incorporating Jewish themes.

Although Yakobson refrained from broadcasting his own Jewish identity in public, Ross has identified gestures and bodily caricatures in Yakobson’s work deriving from the Moscow State Yiddish Theater.

In Vestris (1969), a solo dance commissioned by Baryshnikov, Yakobson employed broken, tragic and aged gestures that typified oppressed Jews. One year later, Yakobson took a greater risk in Jewish Wedding (later renamed Wedding Cortège). During a rehearsal of this ballet, the oversight committee (made up of Communist Party officials) objected to a crawling scene danced by the poor suitor of the bride. The committee ordered Yakobson to omit this movement, on the grounds that Soviet citizens do not crawl on their knees.

Interestingly, Yakobson’s struggle to create modernist, counter-cultural works revealed an interdependent relationship between himself and the regime.

In Ross’ analysis, the making of ballet in the Soviet Union had affordances and constraints. Ballet was valued and privileged as a tool for conveying critical meanings and manufacturing the idealized Russian body. “Ballet gave the artist a certain status. It was worth the struggle because this was such a valued arena. And so they needed Yakobson as well,” Ross said.

Contemporary Russian and American dancers continue to restage and perform Yakobson’s ballets. As Ross put it, they remember Yakobson not only for highlighting prohibited cultural identities and resisting propagandistic agendas, but also as an artist who “paved the way toward a flowering of new dance in the post-Soviet 1990s.”