-

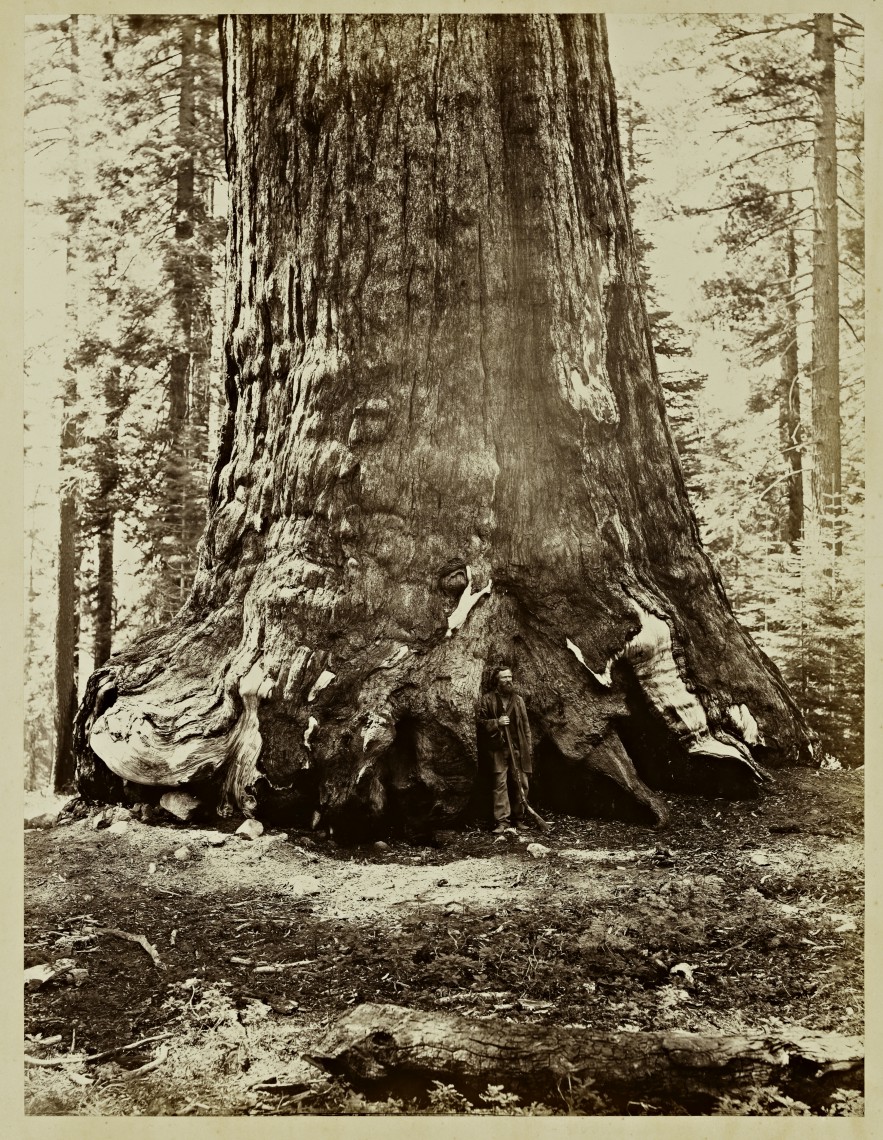

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Section of the Grizzly Giant, 33 ft. diameter, 1865–1866, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Alcatraz from North Point, 1862–1863, from the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Washington Column, 2082 ft., Yosemite, 1865–1866, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

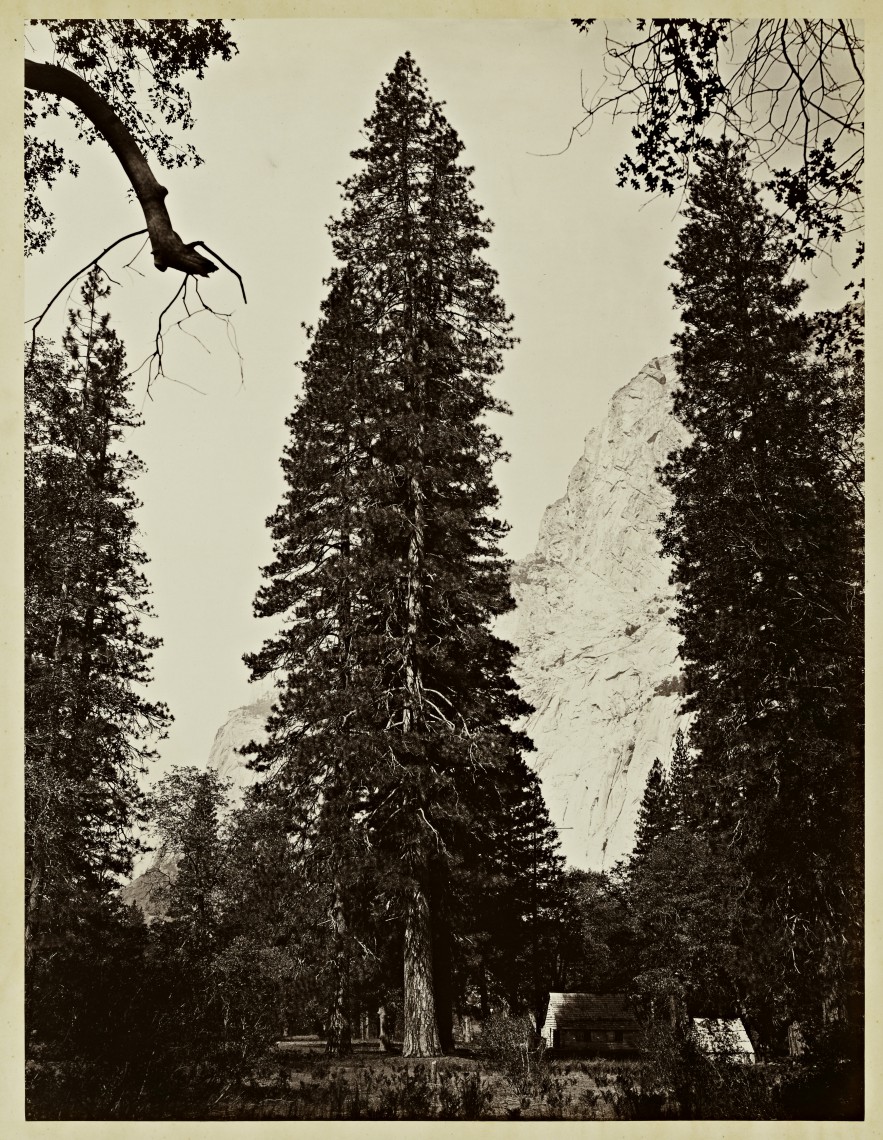

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), The Ponderosa, Yosemite, 1866, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

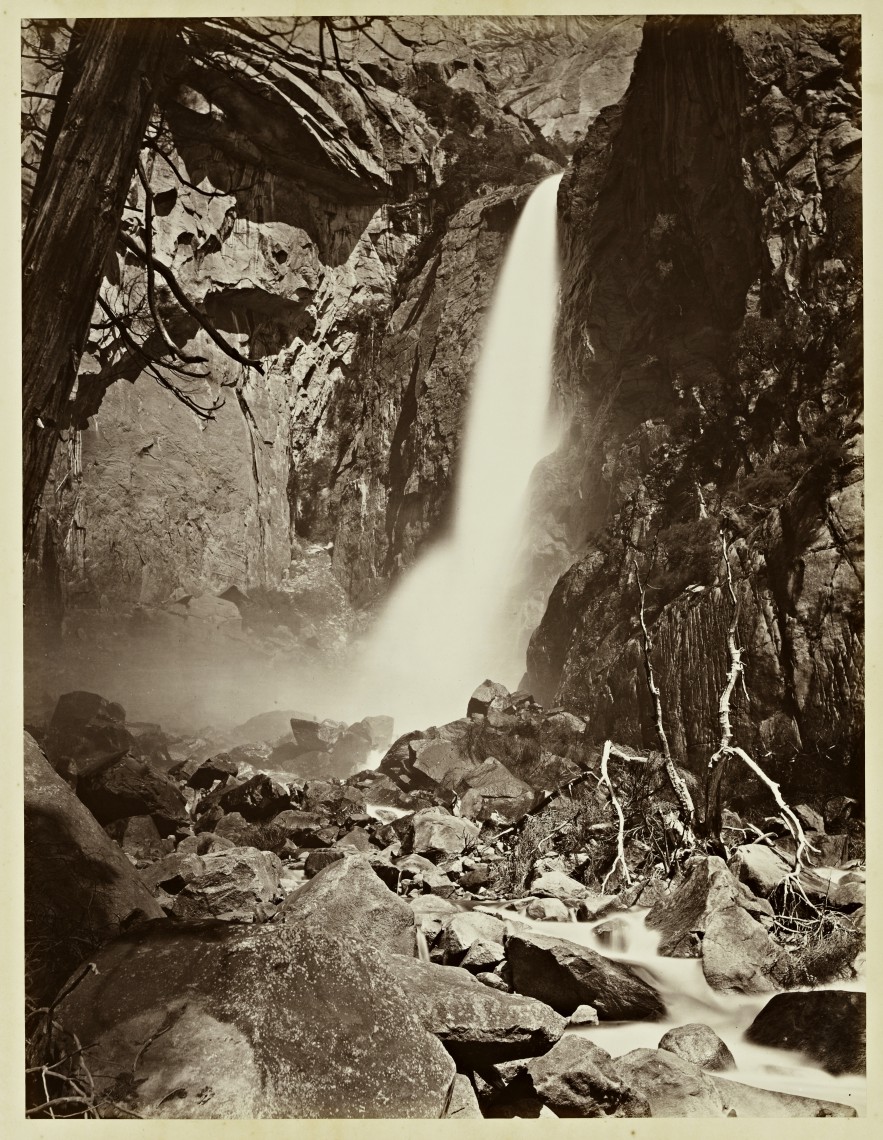

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), The Lower Yosemite Fall, Yosemite, 1865–1866, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

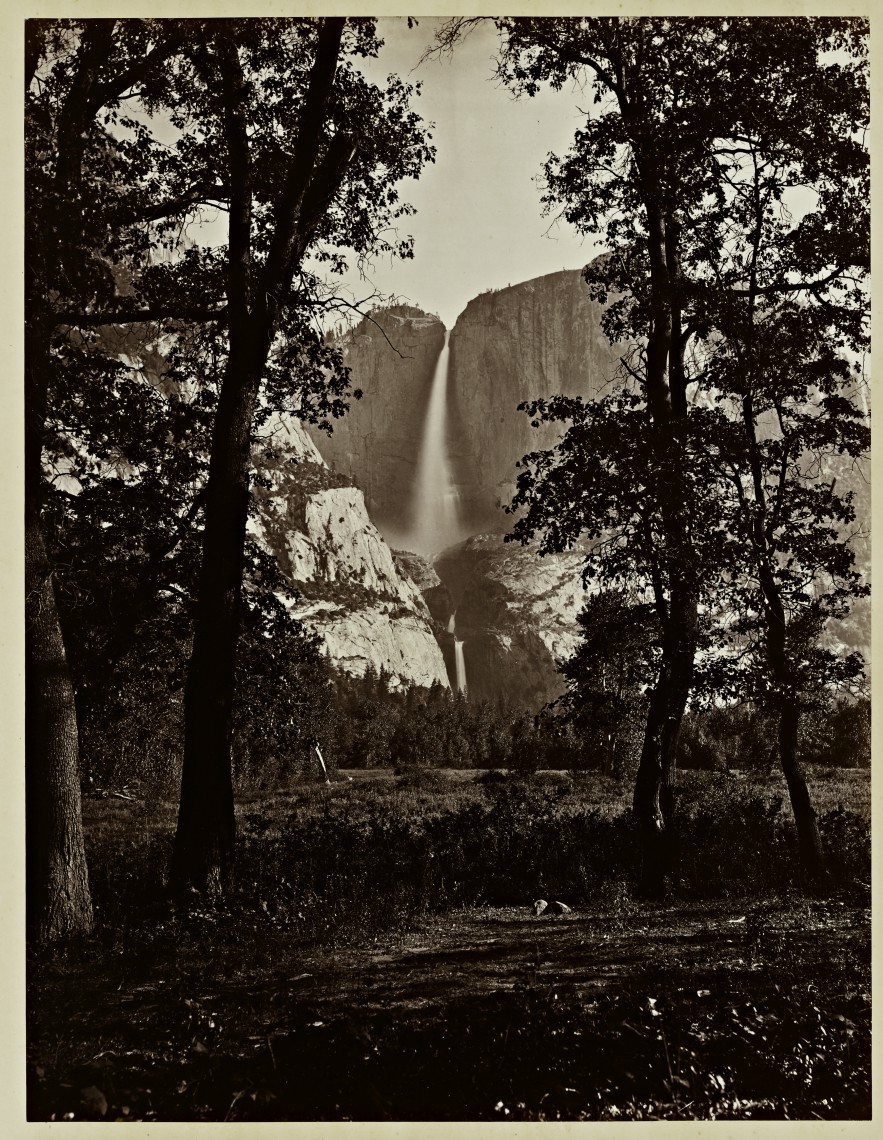

Carleton E. Watkins (U.S.A., 1829â1916), The Yosemite Falls 2634 ft., Yosemite, 1865â66, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Mirror View of El Capitan, Yosemite, 1865–1866, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

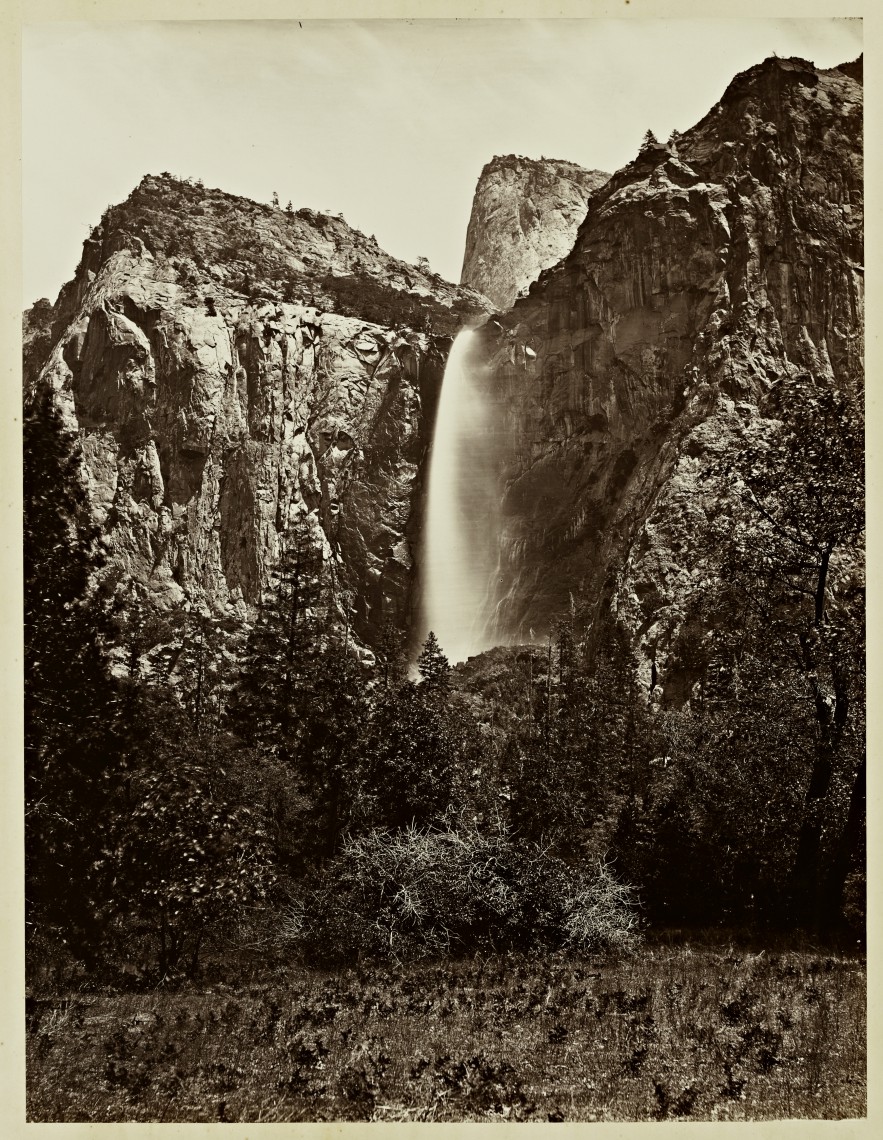

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Pohono, the Bridal Veil, Yosemite 900 ft., 1865–1866, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

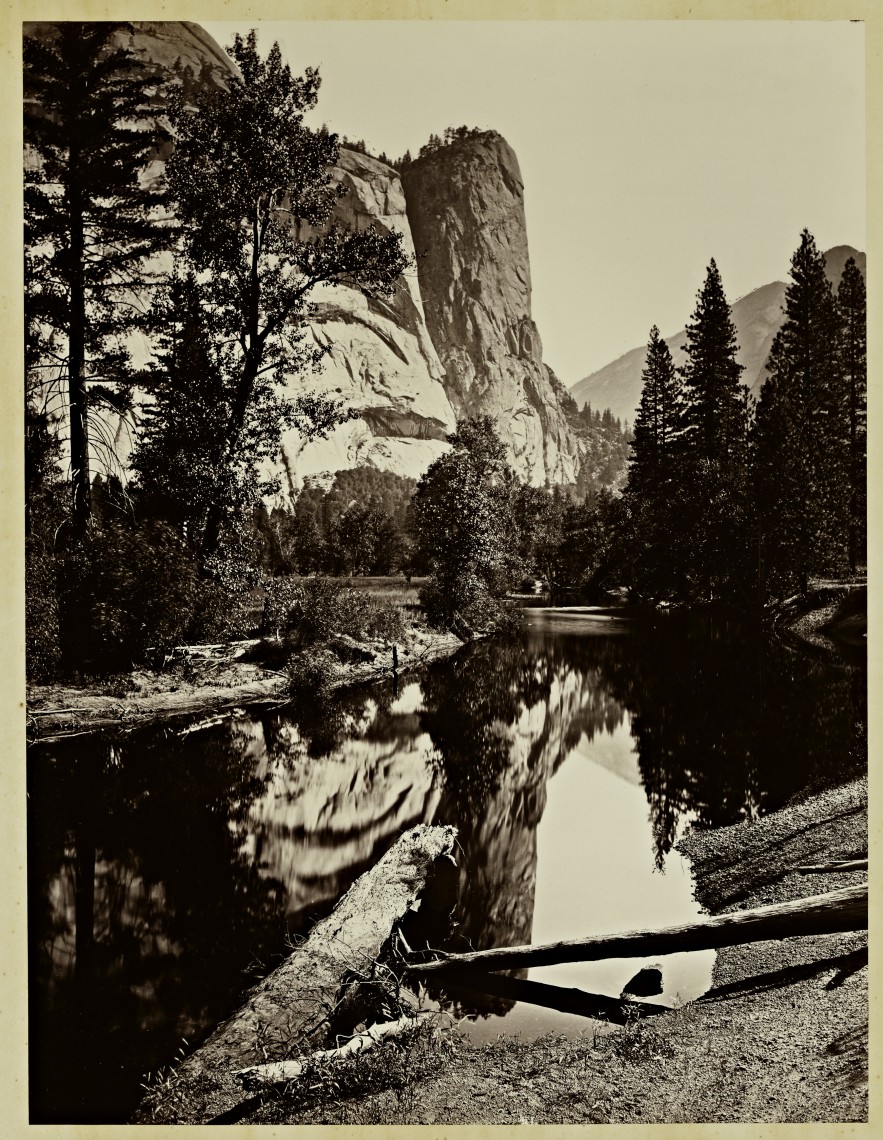

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Mirror View of the North Dome, Yosemite, 1865–1866, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Pompompasos, the Three Brothers, Yosemite 4480 ft., 1865–1866, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

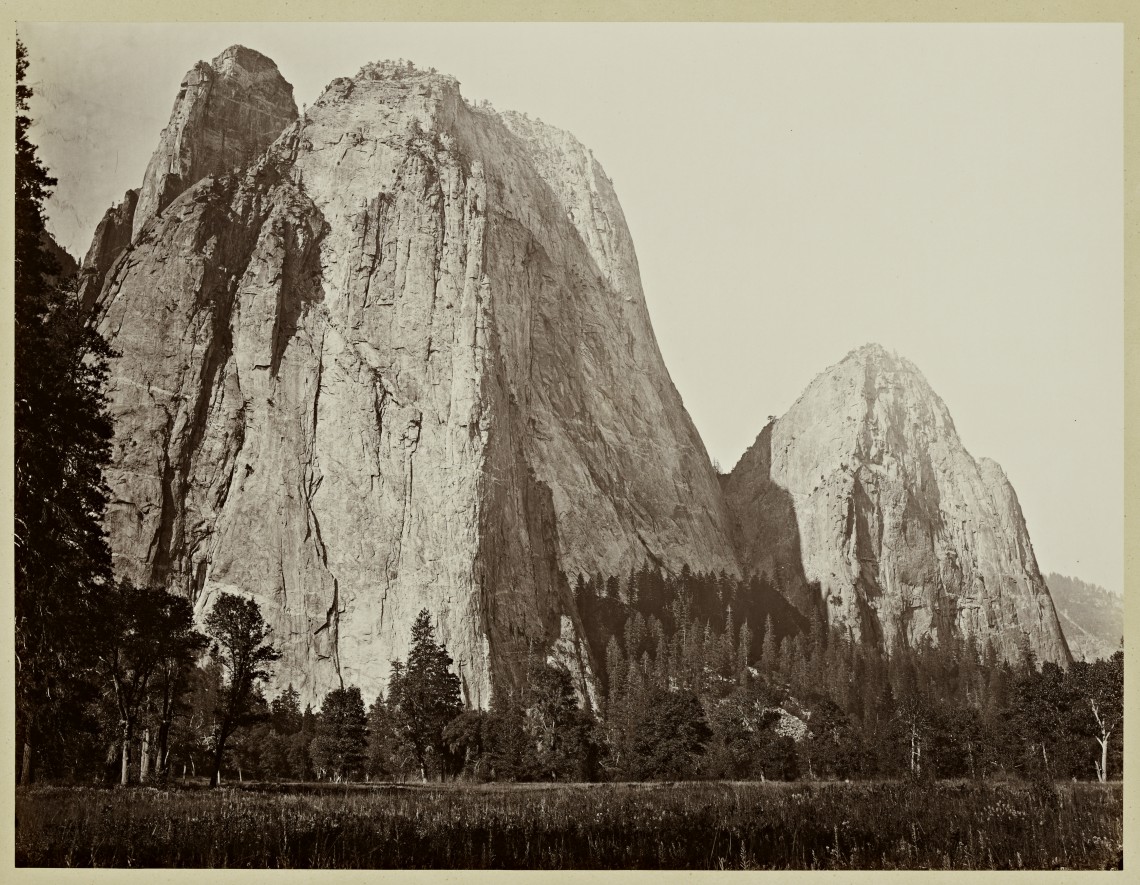

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Cathedral Rocks, 2630 ft., Yosemite, 1865–1866, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), The Yosemite Valley from the “Best General View,” 1866, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Multnomah Falls, Cascades, Columbia River, 1867, from the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Cape Horn, Columbia River, 1867, from the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

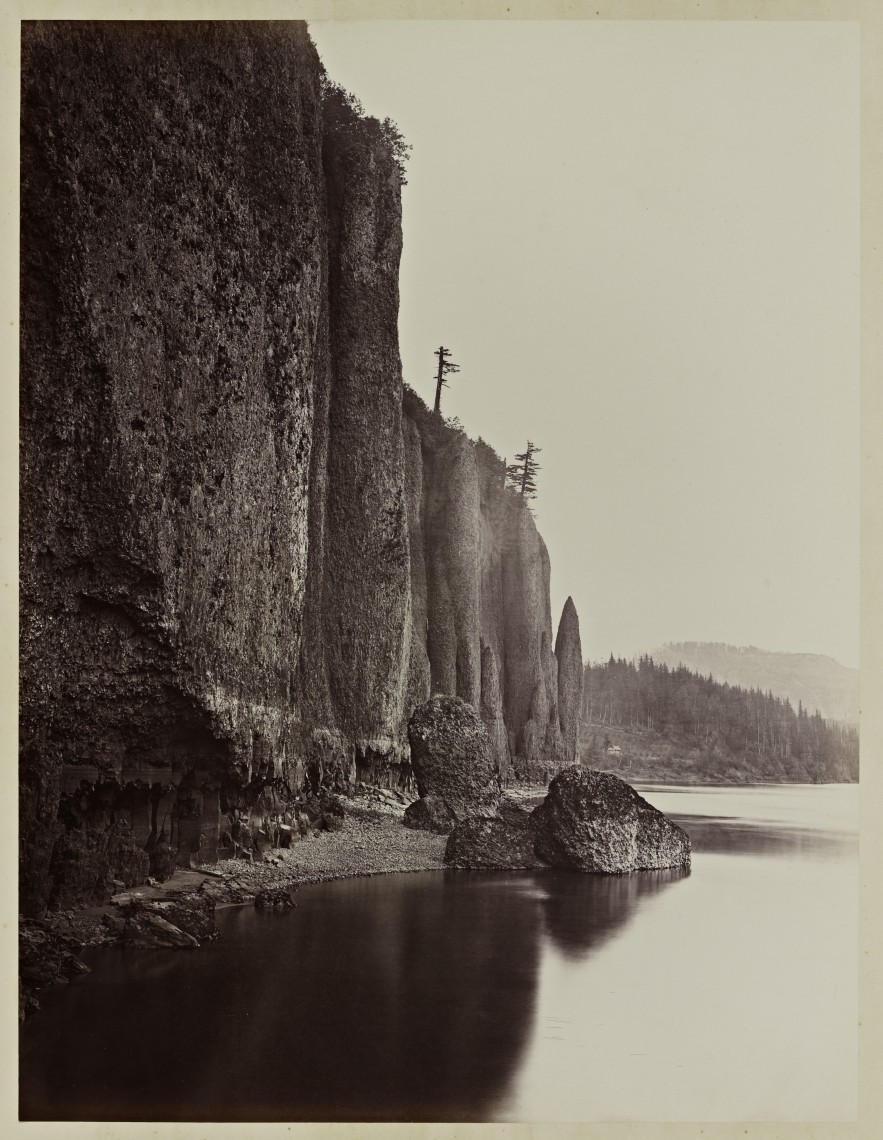

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Cape Horn, near Celilo, 1867, from the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Mt. Hood and the Dalles, Columbia River, 1867, from the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Cape Horn, Columbia River, 1867, from the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Flour and Woolen Mills, Oregon City, 1867, from the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Arch at the West End, Farallones, 1868–1869, from the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916) Sugar Loaf Islands and Seal Rocks, Farallons, 1868–1869, from the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Devils’ Cañon Geysers, Looking Up, c. 1867, from the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), Magenta Flume Nevada Co. Cal., c. 1871, from the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

-

Carleton Watkins (U.S.A., 1829–1916), The Wreck of the Viscata, March 1868, from the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast. Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Stanford showcases Carleton Watkins’ landscape photographs of the American West

A new Cantor Arts Center exhibition of 19th-century landscape photographs is an innovative collaboration reflecting an interdisciplinary approach. The "Carleton Watkins: Stanford Albums" display includes visualizations that provide dynamic context for the geography and natural history behind the photos.

For the fantasy dinner party that one would plan in celebration of Carleton Watkins’ exhibition at Cantor Arts Center, you would start with Watkins at the head of the table.

Add special guests President Abraham Lincoln, who signed the Yosemite Valley Grant Act in 1864 based on Watkins’ photographs; Leland Stanford, who was governor of California when Watkins was creating some of the iconic images of his state and the surrounding region; and Timothy Hopkins, friend to Leland and Jane Stanford, university trustee and donor of the albums to the Stanford University Libraries. Finally, include all the exhibition collaborators.

Those are a few of the historical names associated with the Cantor Arts Center’s new exhibition, Carleton Watkins: The Stanford Albums, now on view through Aug. 17.

The exhibition features 83 original large-format prints from three Watkins albums that are part of Stanford University Libraries’ special collections: Photographs of the Yosemite Valley (1861 and 1865–66), Photographs of the Pacific Coast (1862–76), and Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon (1867).

But it is more than a photographic exhibition. It includes cartographic visualizations developed in collaboration with faculty and students from Stanford’s Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis, the Bill Lane Center for the American West and the Branner Earth Sciences Library. These visualizations provide dynamic context for the geography and natural history of Watkins’ photographs.

Three interactive applications – iPad-optimized websites – show the exact locations where the famous Yosemite exposures were made, guide visitors on Watkins’ path paralleling the Columbia River, and offer interactive before-and-after images using Watkins’ photos of San Francisco.

Nicholas Bauch is a Lane Center postdoc scholar and geographer who worked on multiple iterations and stages of the apps with undergraduate students for five months. He said the photographs in the three albums give many clues about the cultural and environmental history of the American West, but as individual photographs they do not lend a sense of the territories where Watkins did his finest work, why he went there, and how he might have made these journeys. This is where the cartographic accompaniments come in, he noted.

Bauch said, “By looking at the original prints hanging on the museum walls, then being able to analyze the collective nature of Watkins’s oeuvre in the digital accompaniments, visitors to Cantor can truly learn more about the world Watkins traversed to make his famous depictions of an American West that was soon to change dramatically.”

Contemporary collaborations

Most of the collaborators on the exhibition were Cantor staff, the digital strategy team responsible for the cartographic component, catalogue contributors and producers, or the library preservation team. Within each group were specialists in photography, exhibition design, cartography, computer science, symbolic systems, rare maps, rare books, Earth science, history, natural resources law, and more.

Ongoing programs associated with the exhibition brought more collaborators into the mix: a wet-plate demonstrator, an arborist, a university historian and museum docents.

Stanford sophomores Davis Wertheimer and Ashley Ngu were research assistants on the cartographic visualization project overseen by Colleen Stockmann, assistant curator for special projects at Cantor, and Bauch. They researched Watkins’ photographs and helped design and produce the iPad apps that add a tech layer to the viewing experience. Ngu is majoring in computer science and minoring in art practice; Wertheimer is majoring in symbolic systems and minoring in math.

Wertheimer said, “The idea behind the apps was to contextualize the photos for visitors in ways that the usual wall label cannot – for example, by showing how the scenes have changed through time, where Watkins was and what he was looking at as he took each photo, or where the pictured landscapes are located relative to each other and the larger geography.”

Wertheimer added that other recent technologies were crucial in uncovering the information needed for the apps. “In order to figure out where Watkins was standing when he took each photo, we had to use a combination of detailed satellite imaging, virtual terrain modeling and cloud-based geological survey data.

“This was an extremely interdisciplinary project, and to do it justice we needed different people approaching it from different angles. We needed researchers, designers, curators, cartographers, photographers, programmers and historians. Everybody brings something different to the table, and that’s really what an open-ended project like this one needed.”

19th-century sensation

Watkins’ photographic achievements under adverse conditions were unmatched and astonished his peers.

The suite of Yosemite photographs became an international sensation – not only because they provided virtual access to one of America’s grandest wilderness areas but also for their extraordinary beauty. The New York Times declared in 1862, “As specimens of the photographic art they are unequaled.”

Curator Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell agreed: “Watkins’ mastery of his craft and his feel for the landscape enabled him to create iconic pictures of California and the American West, and this collection is one of Stanford’s greatest art treasures.”

The accompanying catalog published by Stanford University Press reproduces all 156 photographs in the albums and features 17 essays by Stanford faculty, staff and associated scholars. The albums themselves are substantial and old, which required a team of Stanford library staff experts to ready the prints for the exhibition.

Roberto Trujillo, head of the Department Special Collections for the Stanford Libraries, said, “This presentation of this many photographs for a single exhibition has never happened at Stanford before. It is a wonderful exhibit to experience and it was a special privilege to collaborate with so many colleagues on the Stanford campus.”