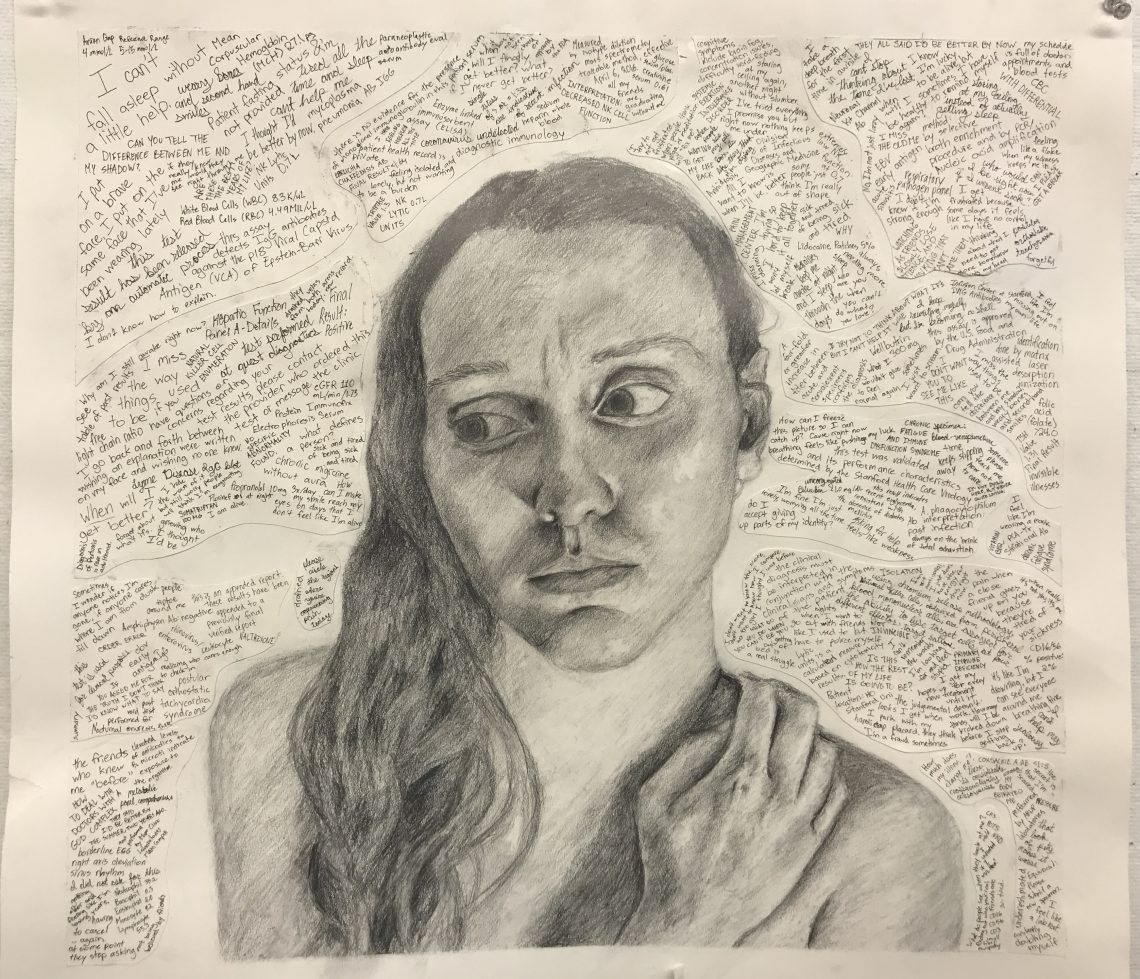

Chocolate Heads dancer at Cantor Arts Center.

Toni GauthierStanford’s Chocolate Heads dance around the theme ‘synesthesia’

The group of dancers, musicians and spoken word artists learn to put their talents together with jazz master William Parker and each other.

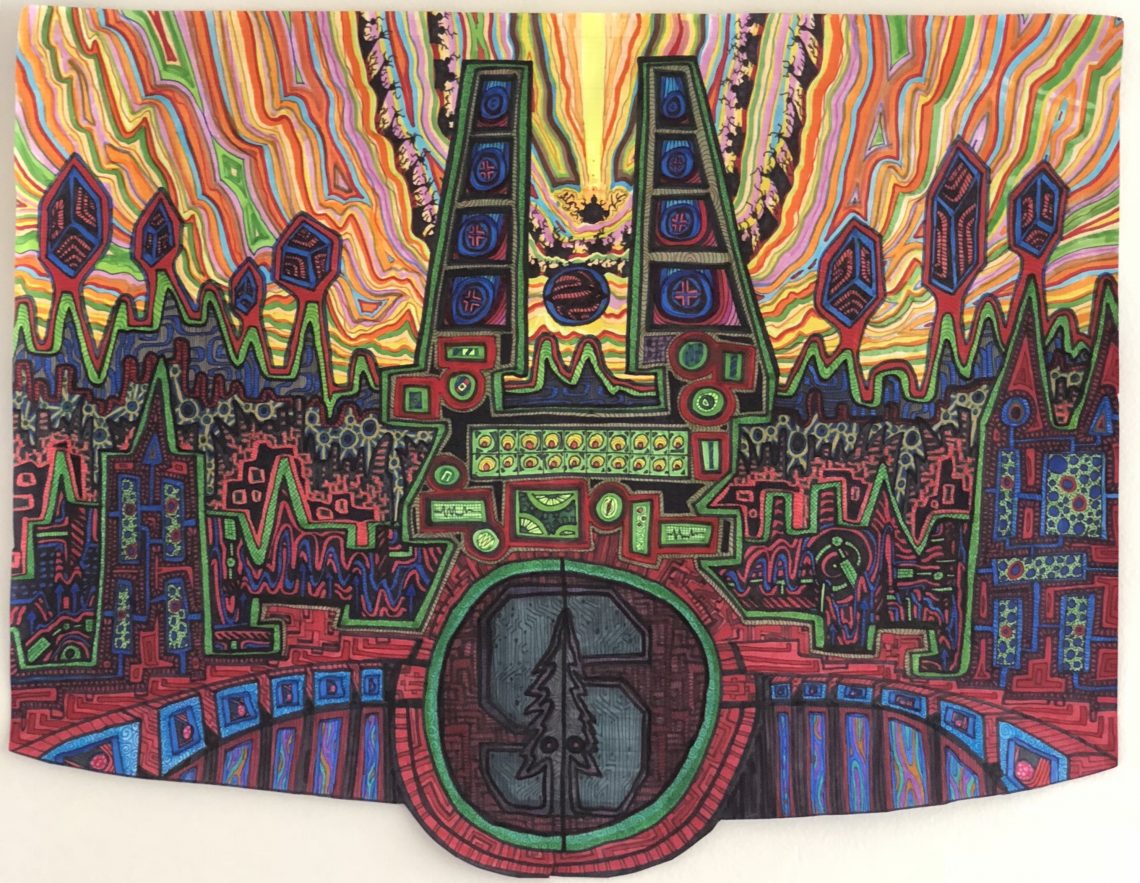

The Bing Concert Hall box office ran out of tickets for the upcoming Chocolate Heads performance in just three hours. The Heads, along with their muse and mentor this year, William Parker, clearly have a following. The 842 lucky ticketholders will be among the first to see dance performed in the new hall and experience the unity of movement and sound that is the trademark of Chocolate Heads.

When Stanford Report last checked in with the Heads in December, the seven musicians in the band had just concluded a weeklong workshop with bassist and jazz luminary Parker, who taught them his method of improvisation and optimizing one’s instrument.

A recent visit with members of the group, this time with the dancers, found them fine-tuning their “events” (Parker’s name for individual compositions) on the heels of a trial run at the Cantor Arts Center and before the big event at Bing.

“You can expect to traverse through multiple worlds, including African dance, athletic football movement and pedestrian ballet,”

For the performance, they are using the neurological condition known as synesthesia, where the senses are conjoined or mixed, to explore how spoken word can be dance and how movement can be music.

“The concept of the show is based on synesthesia and the human experience. You can expect to traverse through multiple worlds, including African dance, athletic football movement and pedestrian ballet,” said student dancer Ben Cohn, referencing just a few of the numerous events the group will present in their upcoming performance.

The fulfillment of the concept is realized when the members of the movement band are able to immerse themselves in every sense of the dance and music experience. Second-year medical student and Heads dancer Bonnie Chien provides a synesthesia example: “In the pedestrian ballet piece, I try to maintain as much tension, focus and gaze through multiple sensory engagement, including the visual, tactile and auditory senses.”

Dancing at the Cantor

The pop-up performance at the Cantor Arts Center, where the group previewed their Bing events, came about when Dance Division faculty member and Chocolate Heads director Aleta Hayes went looking for an unexpected performance space for the group and ran into Connie Wolf, director of the Cantor and always a willing collaborator. The two hatched a plan for Chocolate Heads to take over the Cantor lobby, with its recently restored skylight, where visitors could view the performers from the stairs and balcony.

Patience Young, the Cantor’s curator for education, saw the performance as an opportunity to welcome a new student audience and utilize the museum in a new way. With little time to prepare and only one opportunity to get it right, Young reported that the venue worked amazingly well.

Tamer Shabani

For Chien, the Cantor performance allowed her to see the band’s dancing through the eyes of an audience for the first time. “Someone interpreted one of the movements as raindrops when we were snapping our fingers, and when we elevated in height as a tree growing out of the ground.” Chien also said the audience helped inform her understanding of her own piece. “They increased my awareness of what I was doing.”

Favorable feedback at the Cantor on the athleticism, unexpected compositions and non-traditional movements sweeten the group’s anticipation of their next performance. “I’m excited to see people surprised when we perform at Bing,” said Chien. “I hope we perform in ways that are unexpected for the audience, who can synthesize our melding of the senses and diverse styles for themselves. That is how I view synesthesia – a creative and intensely personally resonating process that flows and connects us.”

What comes first, the music or the movement?

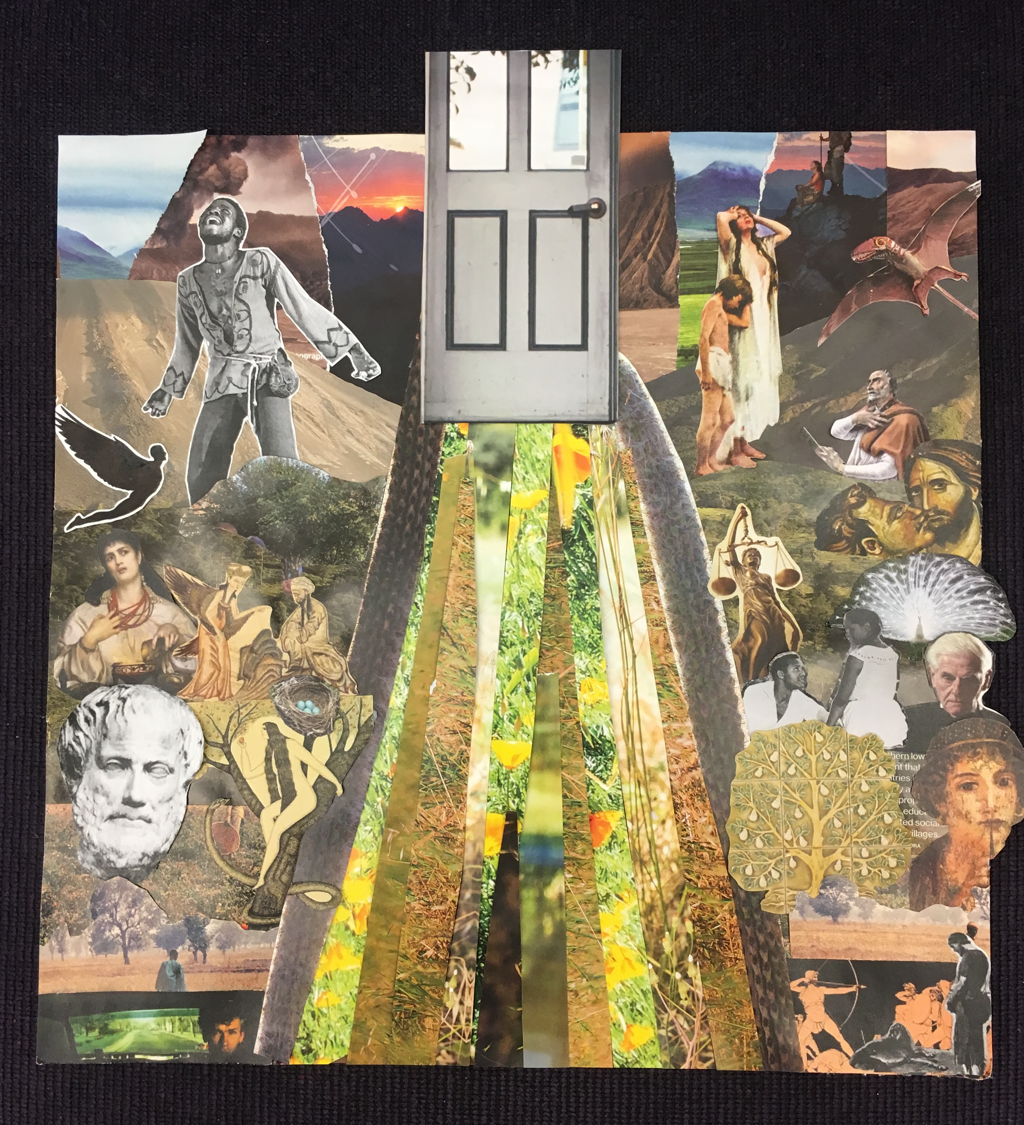

The movement component to Chocolate Heads comes from the 14 dancers in the group. When asked how the music and Parker influenced the choreography and movements, the answers varied.

For Cohn, his choreography inspiration came primarily from the spoken word artists or in response to other movements. He had something worked out physically before he engaged with the music.

Chien took a similar approach with her non-classical ballet events and developed movements before hearing the music. “For my pieces in particular the music is quite spontaneous. When we performed at Cantor, the musician improvised on the spot. It felt very much like a call and response. We listened to each other to integrate the music and dance.”

Undergraduate Olivia Smarr is trained in West African dance, which she describes as very rhythmic and completely connected to West African percussion. Her Chocolate Heads event is rooted in African dance but it has a contemporary twist because the accompanying drums are Western.

“The music has modified a lot of my dance and made me think differently about how to translate the moves that I know to match the sound that we have. The sound of a Western drum set is very different than the sound of an African drum, so the movement is also different,” she said.

“We’ve all got different backgrounds in the arts, whether it’s dance or spoken word, and musicians have their own disciplines and methodologies, backgrounds and training,” said student Logan Richard. “But something that really resonated with me at the beginning of this year was when Aleta Hayes said that the intention of Chocolate Heads is to identify the different languages of the arts and create a fusion.”

For Richard, the fusion came together in preparing for the Bing performance. In speaking about his event, Nat and the Boys, a piece that is influenced by surfing, football and wrestling, he said there was separation between choreography and music in the beginning, but the elements of creation eventually started to overlap when the group started crafting the Bing show. “We started to time our own cadence or movements using our breath or the crescendos of the music and we began to see more of an interplay.”

Someone who is neither a dancer nor a musician, but still a vital part of the movement band fusion, is undergraduate spoken word artist Brittany Newell. She, along with two other spoken word artists, participated in hip-hop and “spitting” word delivery exercises with Parker and said it informed her writing.

“The poet’s role is to observe the dance and partake in the music somewhat, and then try to distill the essence of the pieces into a few lines that are as evocative and direct as we can make them,” said Newell, adding that there is a strong parallel between music and poetry in Chocolate Heads and they are both providing the voice of movement.