-

Charles-Joseph Natoire, Neptune and Amphitrite, circa 1730s. Black chalk with brush and brown wash and white heightening on blue laid paper. 9 7/16 in. x 14 9/16 in. The Suida-Manning Collection. Blanton Museum of Art.

Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center -

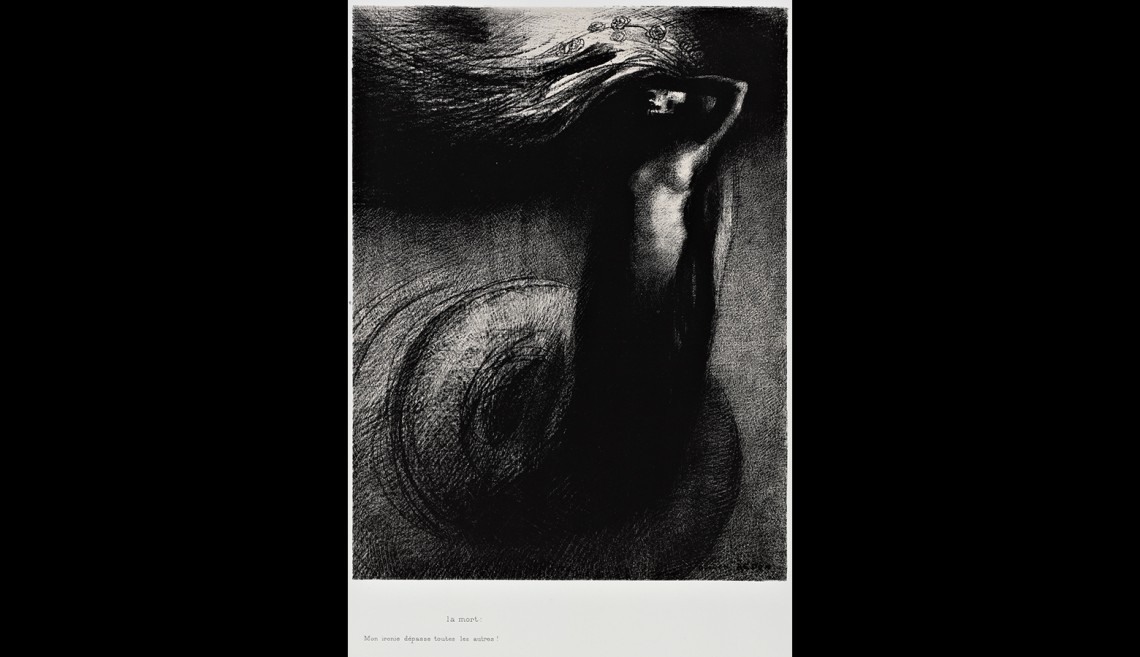

Odilon Redon, Death.

Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center -

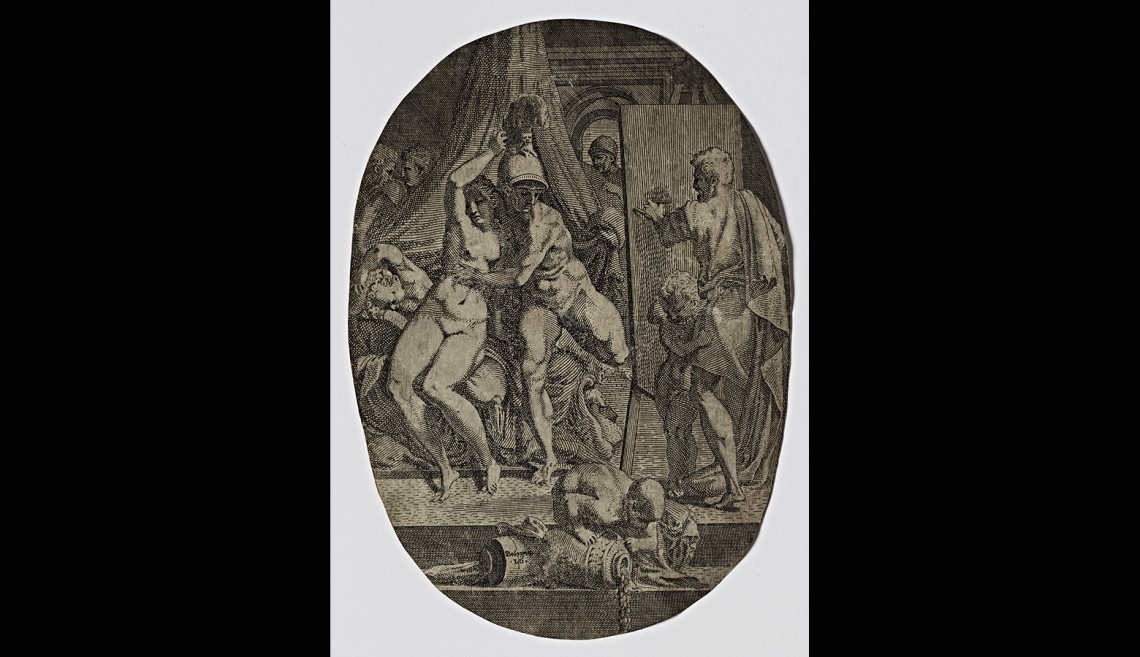

Edouard Manet (France, 1832–1883), Civil War (Guerre civile), 1871. Lithograph. Committee for Art Acquisitions Fund.

Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center -

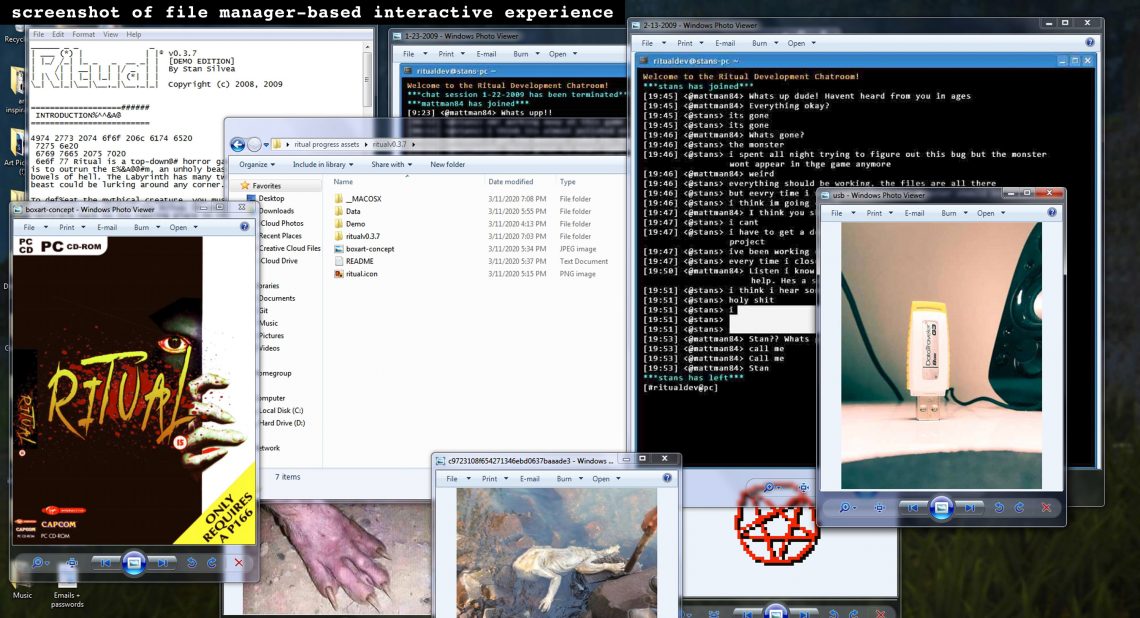

Apelles Painting Alexander and Campaspe by Leon Davent is among the works in the exhibition A Royal Renaissance: School of Fontainebleau Prints from the Kirk Edward Long Collection.

Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center -

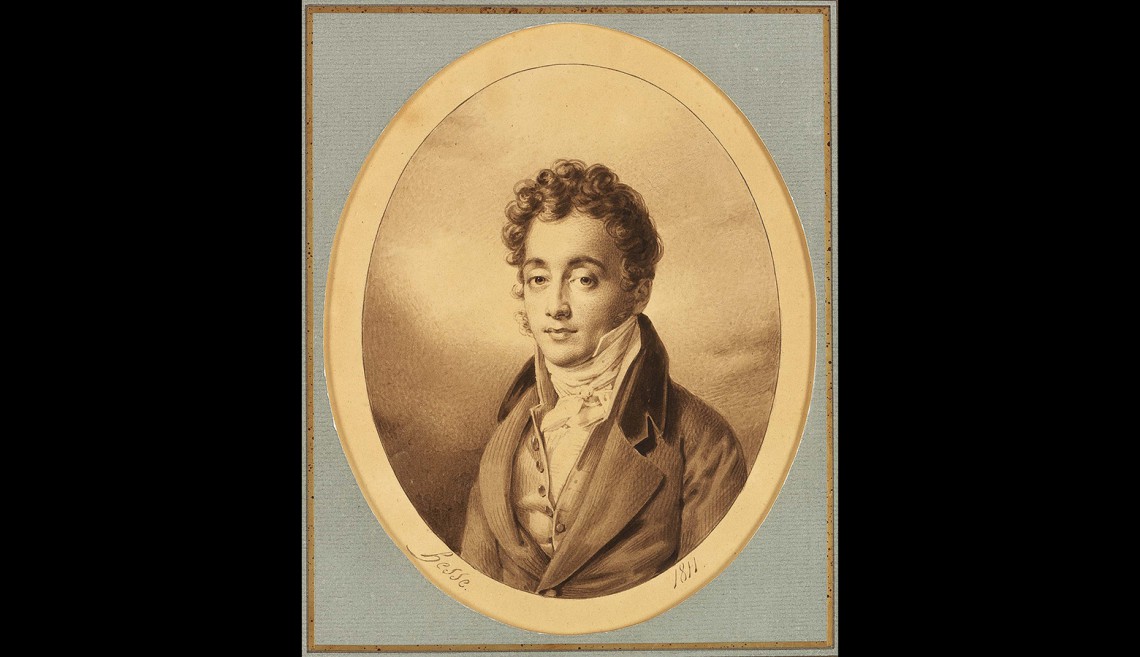

Henri-Joseph Hesse, Portrait of a Man, 1811. Brush with brown ink and white heightening over traces of black chalk on beige wove paper. 9 1/4 x 7 5/8 inches. Archer M. Huntington Museum Fund, 1987, 1987.19. The Blanton Museum.

Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center

Cantor Arts Center’s French summer

Six exhibitions highlight five centuries of French art from private and permanent collections. Staff members pick their favorite works.

Never mind that King Francois I of France pre-dated Bastille Day by more than 200 years. The sophisticated and extravagant School of Fontainebleau style that developed under his royal command is something to celebrate and see during the month of France’s La Fête Nationale.

Francois’ 16th-century prints, le quatorze juillet, on view through Sunday, are part of a French summer at Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center. In all, there are six exhibitions showcasing French works from private collections and the Cantor’s permanent collection on view throughout the summer. Seven if you count the perennial display of 200 works by Rodin in three galleries and the outdoor sculpture garden.

While French art is not new to the Cantor, it is unusual to display so many works from a single country.

“Though the Cantor is rightfully known for our Rodin bronzes, we also have exceptional holdings in French works on paper from the 16th to 19th centuries,” explains Connie Wolf, the director of the Cantor. “Our exciting collaborations with the Blanton Museum of Art [Storied Past] and Stanford’s Special Collections [Matisse Jazz] presented the ideal opportunity to showcase this aspect of our collection in full historical context.

“As these light-sensitive works can be on view for only months at time, we elected to exhibit them concurrently, so our visitors can experience the breadth and depth of what the Cantor has to offer,” she said.

Several Cantor staff members agreed to share their favorites from the six exhibitions:

A Royal Renaissance

A Royal Renaissance: School of Fontainebleau Prints from the Kirk Edward Long Collection closes July 14. Not to be missed among the 30 works on view is curator Bernard Barryte’s pick, Apelles Painting Alexander and Campaspe by Léon Davent.

King Francois I of France wanted the world to know him as highly cultured; so he directed prominent engravers to record the multimedia ensembles that embellished his over-the-top royal residence at Fontainebleau. The resulting works in A Royal Renaissance illustrate the sophistication, extravagance and eroticism of this courtly style.

Barryte says of his pick from the exhibition, “Among my favorites is Léon Davent’s Apelles Painting Alexander and Campaspe for two principal reasons. First, the composition and figures encompass all the mannered grace that is characteristic of the School of Fontainebleau, so it is a really elegant example. Second, the narrative exemplifies its propagandistic purposes so well – for both artist and king.

“Here’s the story that is illustrated: commissioned to paint a portrait of Campaspe, the favorite mistress of Alexander the Great, Apelles fell in love with the concubine. When he noticed the situation, Alexander, in an act of vast generosity, gave the woman to the painter. So, from the artist’s point of view, the episode promotes the ideal of generous patronage; from the king’s standpoint it celebrates magnanimity. Of course, no one asked Campaspe how she felt about the situation.”

Storied Past

Throughout history, artists have sought new ways to tell stories with images. The introductory panel for Storied Past: Four Centuries of French Drawings from the Blanton Museum of Art, on view through Sept. 22, describes how centuries of French draftsmen gave visual form to narratives. It reads: “Their diverse subjects come from biblical history, mythology, literature and scenes glimpsed in daily life; they include imagined landscapes, insightful studies of the human figure, and likenesses captured in portraits and satires. These preliminary sketches, detailed studies and finished compositions provide a broad view of the expressive and technical range fostered by the French tradition.”

A standout work for curator Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell is Charles-Joseph Natoire’s chalk and ink drawing Neptune and Amphitrite, dated to the 1730s, which was drawn on blue paper. Blue paper was a precious commodity, and so artists often reserved it for elegant, finished drawings like this one.

Curator of education Patience Young is particularly fond of Portrait of a Man by Henri-Joseph Hesse. “This early 19th-century drawing is delicate and charming, with its attention to textural detail – note those curly locks! – and subtly graduated shadows across temple, cheek and chin. Not least is the steady and somewhat penetrating gaze of the sitter.”

Drawn to the Body

Drawn to the Body: French Figure Drawings from the Cantor Arts Center Collection is a curatorial amuse-bouche installed in a gallery within Storied Past, and is also on view through Sept. 22. Mitchell selected works that range from highly finished studies to delicate sketches, all created between the late 18th and the early 20th centuries.

She writes, “Traditionally it was imperative for draftsmen to master the ability to accurately draw a nude body, and then add clothing onto this base. This exercise trained the eye and the hand to convey gesture, action, emotion and style through line. Each of the approaches apparent in these drawings offers great insight into an artist’s working process.”

Mitchell says one of the more surprising and charming drawings in the installation is Honoré Daumier’s Hercules in the Augean Stables, “a humorous and scratchy pen and ink composition from the 1840s, that captures a paunchy Hercules in profile.”

Young calls special attention to Edouard Vuillard’s Studies of a Seamstress, an exceptionally free and airy ink drawing.

“Vuillard reveals how representation of a woman in nine vignettes can be abstracted to an extreme degree, anticipating the modernism of the 20th century,” she says.

Inspired by Temptation

Death: My Irony Surpasses All Others! is singled out by curator Judy Koong Dennis from her exhibition Inspired by Temptation: Odilon Redon and Saint Anthony, on view through Oct. 20.

“Upon reading Gustave Flaubert’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony, French painter and printmaker Odilon Redon was immediately struck by its pictorial possibilities, calling the book a ‘marvel and a mine,'” writes Dennis. “Against the backdrop of a society confronting changes brought by industrialization, scientific discoveries, the provocative theories of Charles Darwin and Sigmund Freud, and France’s crushing defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, Flaubert’s prose-poem crystallized society’s struggle to understand three essential questions: Where do we come from? What is the point of existence? Where do we go from here?

“Giving shape to Redon’s own dreams, horrors, and fantasies, Flaubert’s book inspired the artist to create the three lithographic albums on view in this exhibition.”

Dennis’ pick from the 42 prints in the exhibition is one of Redon’s best-known and most compelling works. “I love the title. As Redon visualized the scene, Death’s black gown envelops Lust’s naked white torso. Death’s skull floats above Lust; a veil with a garland of roses appears to trail above their merged bodies. Swirls in the lower half of the image suggest a vortex or a long, coiled tail.

“Death is an excellent example of Redon’s mastery of the lithograph medium. His friends and contemporaries, Paul Gauguin among them, greatly admired the range of blacks – from the deepest black to the softest gray – that he was able to achieve. The medium was perfect for communicating the atmosphere of terror described by Flaubert.”

Manet and the Graphic Arts

The central image in Manet and the Graphic Arts in France, 1860–1880, on view through Nov. 17, is Edouard Manet’s powerful lithograph Civil War (Guerre civile) – a staff favorite. It depicts the deadly aftermath of the downfall of the 1871 Paris Commune. Famously, it isn’t clear which side the fallen soldiers were fighting for.

“The death and destruction that occurred in the streets of Paris during the Commune of 1871 affected artists of the generation who lived through it or even fought in it, as did Edouard Manet,” writes Mitchell in her text panel. “This exhibition examines how printmakers, draftsmen and photographers depicted the factors that led to this traumatic event as well as the conflict itself and the changes it brought to Paris.”

Jazz

In 1943, French artist Henri Matisse was more than 70 years old and bedridden when he began the portfolio that eventually became Jazz. Limited in his mobility, Matisse cut out forms from colored papers that he arranged as collages. His assistants then prepared the collages – most of which were based on circus or theater themes – for printing in the pochoir screenprint process. The final French Summer exhibition, Matisse Jazz, which runs July 31 through Sept. 22, features all 20 prints from the edition of the portfolio held in the Gunst Collection in Special Collections at the Stanford University Libraries.

“The image of Icarus with its simple form and bold colors is one of my favorites,” said Wolf. “Despite its simplicity, the image is a powerful representation of the famous myth. I am so moved by how the only detail of the figure is a heart, indicating how vulnerable we all are and how valuable each life is. Matisse is one of those great artists of all times who can convey so much with so very little.”