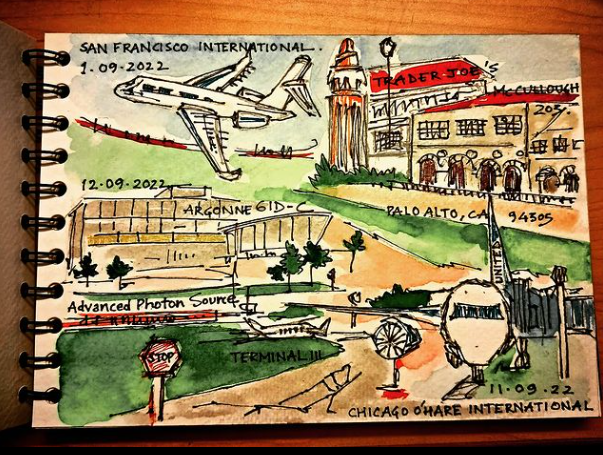

Mariel Lanas's 'Tile Chair,' which is made of laser-cut Baltic birch plywood and nylon line, looks fragile but is surprisingly strong.

Linda CiceroDesign and mechanical engineering share a seat in Stanford’s Product Realization Lab

Goldilocks would be hard-pressed to find fault with any of the chairs, designed by students, now on view in Cummings Art Building. They all appear to be just right in their own way.

The signs on the chairs read, “Please do not sit,” but these chairs were in fact designed for sitting – or reclining, in one case.

A selection of seven seats of distinction, products of the Stanford spring course ARTSTUDI 262, “The Chair,” are currently on view in Cummings Art Building. The temptation, of course, is to try out all of them.

Goldilocks would be hard-pressed to find fault with any of the chairs as they were thoroughly and thoughtfully created by a group of advanced product design students. They all appear to be just right in their own way.

ARTSTUDI 262, an upper-level theory-design-fabrication class, is led by lecturer John Edmark, who is best described by his own hyphenation: artist-designer-inventor-engineer.

His interdisciplinary chair class is offered through the Department of Art and Art History, but he has also taught classes in the design division of the Mechanical Engineering Department.

His resumé includes artist-in-residence at the Exploratorium in San Francisco and the named inventor on nine U.S. and foreign utility patents. Needless to say, chairs are in his bailiwick.

During the 10-week course, students were assigned to design and fabricate their own chairs informed by historical reference, anthropometrics, form studies, user testing and materials investigations.

Easy, right? Not according to Justin Fraga, graduate student in mechanical engineering, who said, “I told myself that this was going to be a nice, relaxing experience to finish out my graduate experience here and it was anything besides that. It was very intense.”

Motivated by students

Edmark was motivated to create an interdisciplinary class that focused on a single project after repeatedly hearing students express a desire to have more time to refine their projects. Most classes require students to work on several projects each term or to work in groups, but ARTSTUDI 262 is different. Ten weeks. One chair. On your own.

When asked why the chair, Edmark responded, “Many designers and architects design a chair at some point in their career. Chairs have an intimate relation to the human form, and as such embody the imperative of user-centric design.

“A successful chair must meld a complex set of factors including aesthetics, ergonomics, structure, materials, purpose and meaning. As such, it affords advanced students an opportunity to draw together the many facets of their design education and bring them to bear on a single substantial project.”

As ubiquitous as chairs are – people use them more than any other piece of furniture during waking hours – Edmark believes that there is always room for a fresh idea.

“Chairs come with specific, clear constraints, but also tremendous expressive freedom,” he said. “This is an opportunity to make an iconic object that has a long and rich history in the world of design. The chair is a classic design project.”

Partnering with Edmark on the fabrication component of the class are David Beach and Craig Milroy, who teach mechanical engineering and are co-directors of the Product Realization Lab. Given the extensive use that the chairs class makes of the PRL, one might easily assume that the Mechanical Engineering Department was offering the class.

Beach said he is delighted to support Edmark’s class because of his and Milroy’s ongoing interest in studio arts and because “it is exhilarating to see students connect with their work in our lab.”

The goal of PRL is to foster a community of creativity where ideas turn into reality. The facility is open to students from all disciplines who want to make useful and beautiful objects. Beach’s mantra is “making is thinking” and he believes that projects like designing and making a chair are important in the development of a fully realized Stanford student.

“I love the PRL. It is central to every good experience that I’ll look back upon when I think about my graduate degree here at Stanford,” said Fraga. “The most important experiences that I will recall involve making something.”

How to make a chair

Edmark starts the class by taking students through the rich history of the chair to sensitize them to the best designs.

The history lessons are followed by some fieldwork in a furniture showroom looking at chair heights, angles and seat lengths, among other attributes.

“A successful chair must meld a complex set of factors including aesthetics, ergonomics, structure, materials, purpose and meaning. As such, it affords advanced students an opportunity to draw together the many facets of their design education and bring them to bear on a single substantial project.”

Students test the chairs, feel the materials and inspect the construction. Edmark cautions that chairs can look simple and obvious but they are complex objects when you consider structural requirements, ergonomic needs and context. Students are reminded to consider the purpose and the user when designing and fabricating.

Sketching ideas and developing a point of view come next. Creating a personal design manifesto helps guide the students’ decisions throughout the process. Very quickly, the students find themselves in the PRL exploring ideas, creating full-scale models, testing, learning from mistakes and incorporating feedback.

Next, the students figure out which skills they need to make their chairs. PRL workshops designed to refine their skills include fiberglass molding, wood steam-bending, plywood forming, metal tube bending, welding and sewing.

The final four weeks of the term are spent sourcing materials and making the chairs. While there are no teams or group work in the class, collaboration and assistance constantly take place among students, faculty and teaching assistants. All-nighters are not unheard of when students are engrossed in their work.

Fresh ideas

The seven chairs on view in Cummings through Aug. 10 represent deep thinking, creativity and hundreds of hours of work. Fresh ideas are evident in the use of non-traditional materials, unlikely construction and whimsy.

Matthew Crowley, undergraduate in mechanical engineering, built his chair from glass and concrete, which creates a certain amount of apprehension when one thinks about actually sitting on it – or having to move it. However, Crowley was thorough in his materials research and was able to find modern versions of both materials that are stronger and lighter than their age-old predecessors. His chair is aptly named “Light as Concrete.”

“Tile Chair,” designed by Mariel Lanas, undergraduate in mechanical engineering, was inspired by her love of crochet work and origami. The seemingly fragile chair resembles a nest woven together with yarn that might fold in on itself if it had to support more than the weight of an egg, but her ingenious combination of geometric elements and flexible cord paired with a bowl-and-base design produced a surprisingly strong chair.

Playful titles such as “Twist” and “Chillin'” and features such as an M.C. Escher-inspired design and built-in bounce speak to the humor and delight found in some of the chairs, but comfort and functionality are also important.

Fraga described his chair as a lounge chair on a diet. The blond maplewood and sage green fabric hint at summer in the park and the slightly reclined back strikes a relaxed pose suitable for reading.

Jamiee Erickson, undergraduate in mechanical engineering, who wanted to design something as close to a bed as possible, offered an even more relaxed pose. Her chair, “Relax Deeply Lounge,” is intended to induce tranquility.

Each chair’s personality and distinction come from good design and fabrication.

In writing about his chair, Matthew Blum, undergraduate in mechanical engineering, said, “What results is a conflict between the chair’s practicality and form, its structure and aesthetic quality – a conflict that I will continually work to resolve throughout my career as a product designer.”