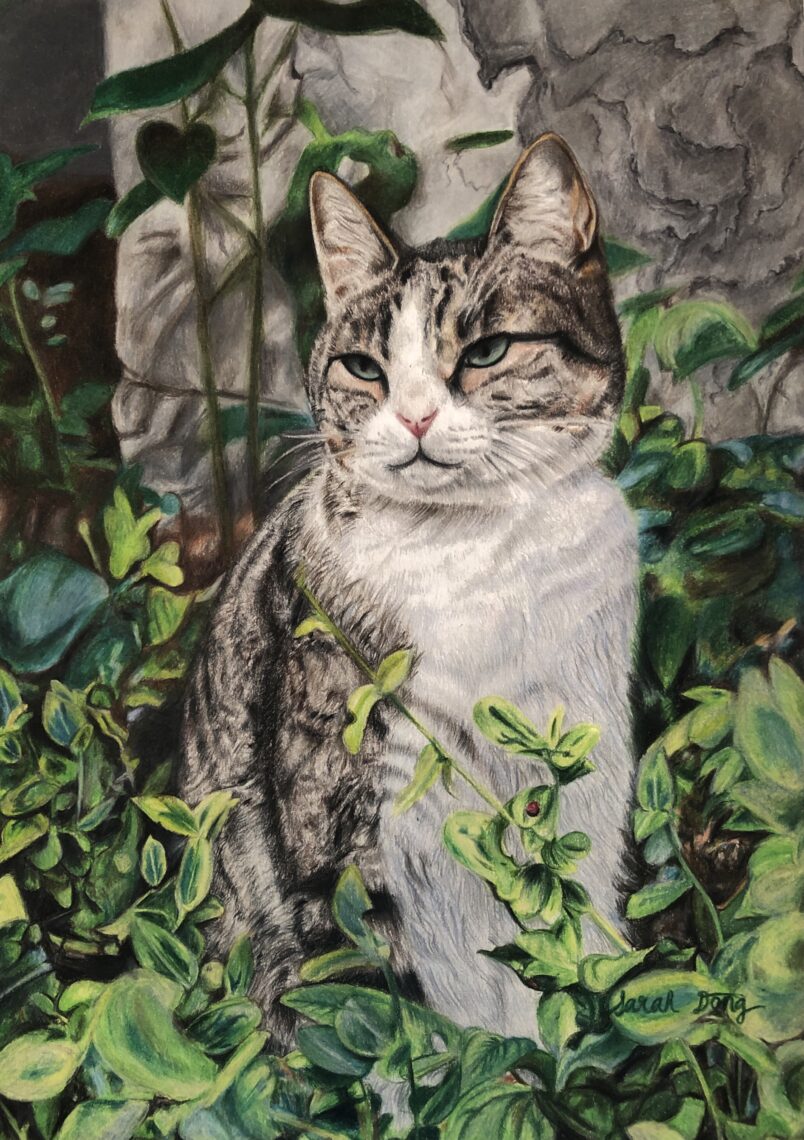

Jay Blakesberg

The Kronos QuartetVisitations: Theotokia and The War Reporter, chamber operas by Jonathan Berger, and Landfall, a collaboration between Laurie Anderson and Kronos Quartet

Stanford Live's new home hosts two major commissions.

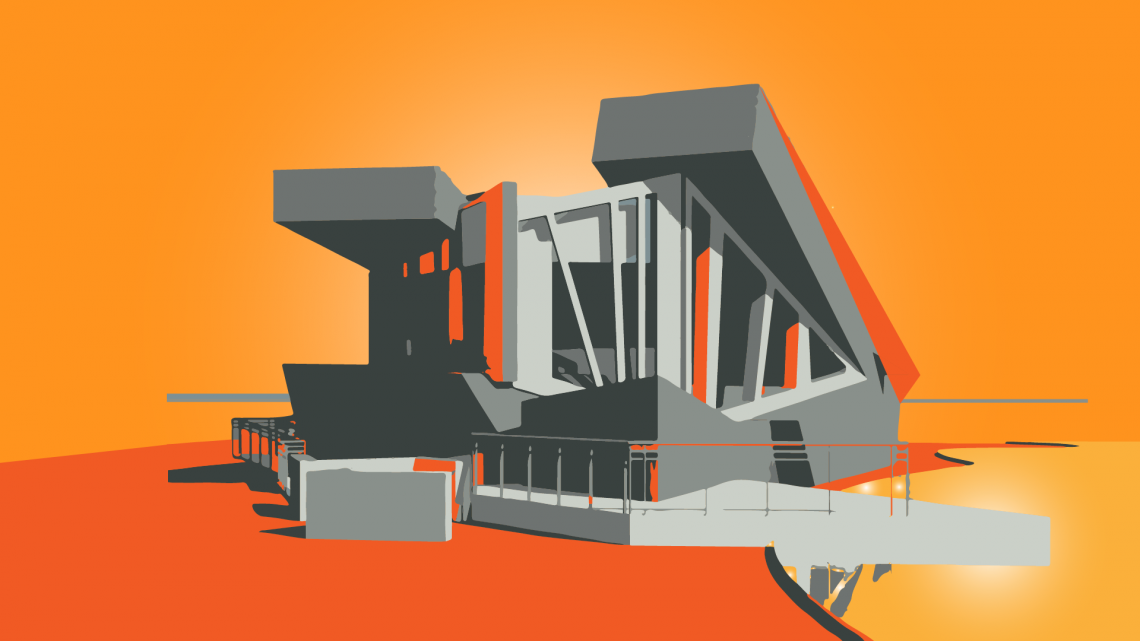

Only a few months after the official opening, Bing Concert Hall has revealed itself to be a masterpiece of organic design ideally suited to intimate, classical performance in a modern setting. At the same time, the space encourages creative exploration and is able to support cutting-edge technology in a way that refocuses the timeless dialogue between performers and audience in a fresh, 21st-century perspective. The hall’s much-admired vineyard style seating leads to both an acoustic and visual intimacy with the artists onstage.

“Although we’ve been purposefully showcasing Bing’s attributes as a superb concert venue,” says Stanford Live’s executive director Wiley Hausam, “this month we are presenting a remarkable range of works.” Audiences will experience the full orchestral sound of the ongoing Beethoven Project as well as the pair of major commissions being unveiled. Laurie Anderson and the Kronos Quartet are joining forces for their first-ever collaboration, while Stanford-based composer Jonathan Berger and maverick director Rinde Eckert rewire the traditional role of the audience in a world premiere double bill of chamber operas centered on the phenomenon of auditory hallucinations.

According to Stanford Live’s former artistic director Jenny Bilfield, who seeded these commissions several years ago, they represent “signature works that are designed to inhabit our new hall.” For faculty composer Berger and for Anderson, Kronos, and the St. Lawrence String Quartet (which performs in the chamber operas)—all familiar artists who have frequently appeared at Stanford—the commissions also serve as “homecomings” that “honor the creative entrepreneurship of these partners within an environment that thrives on invention and imagination.”

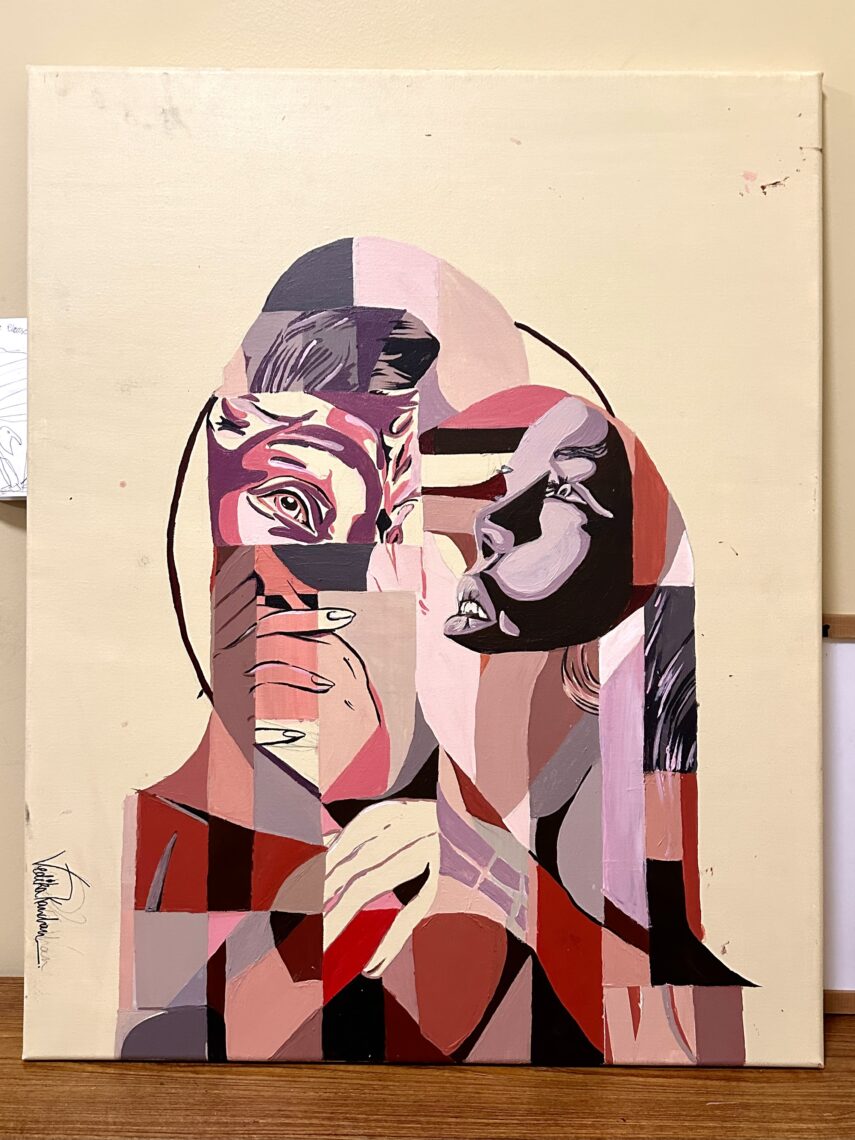

When violinist David Harrington founded Kronos Quartet on the West Coast four decades ago, it must have seemed inevitable that it would collaborate with Laurie Anderson, who was beginning to chart out new territory in New York’s avant-garde performance art scene. Both Kronos and Anderson have continually redefined themselves since but share a commitment to developing their art in ways that can expand our perception.

Still, fans have had to wait until the present commission, titled Landfall (to be performed at Bing Concert Hall on April 20 and 21), to experience what results from such a dynamic combination. “It’s a perfect match in so many ways,” Anderson remarked shortly after the world premiere in February at the University of Maryland’s Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, one of the co-commissioners. “To be part of that group is beyond fun. In some of the wilder parts, it’s like getting into a really fast car with them and driving way past the speed limit!” For Harrington, “The stories she’s telling and the character of the sound—the combination of our arsenal of sounds and Laurie’s palette of options—all of that feels like it’s today’s sound and very current.”

Landfall, a tapestry of “stories with tempos” in which the disruption caused by Hurricane Sandy last fall functions as a “subplot,” also marks a departure in several ways for the polymathic Anderson. “This isn’t about colors or notes or whatever shapes contain the meaning that the audience unwraps. Landfall is much more about how you discover yourself in the act of seeing how something relates to or reminds you of something else—about looking not for meaning but for resonance, using a number of different kinds of codes.”

Comprising dozens of “smaller kaleidoscopic pieces that were knit together in various ways,” Landfall uses new text software (Erst) specially designed for Anderson. This software allows the instruments to trigger an intensely rhythmic language, eliciting strangely unexpected interactions between music and text— written and spoken. Anderson points out that she became fascinated by the disparity between “reading or thinking about something and hearing something different,” which she likens to the perceptual gap between glancing at opera surtitles and listening to a singer’s florid phrasing of a simple statement. The sound of Landfall also mingles acoustic and electronic sources that collide in unusual ways.

“You never sense that you are witnessing technology for its own sake,” explains Harrington. “Laurie’s work always has an elegance and a restraint to it.” One aspect of the collaboration he finds particularly exciting is how Landfall will be reconfigured for the various performance spaces lined up on their current tour. “Music has been at the heart of Bing Hall’s design,” he says, and the intimacy of the space should be especially suited to what he calls Landfall’s largely “elegiac” character and “beautifully shaped form.” It’s also a theatrical piece that features carefully tailored staging and lighting effects. Adapting all this to Bing’s particular ambience “will be part of the adventure.”

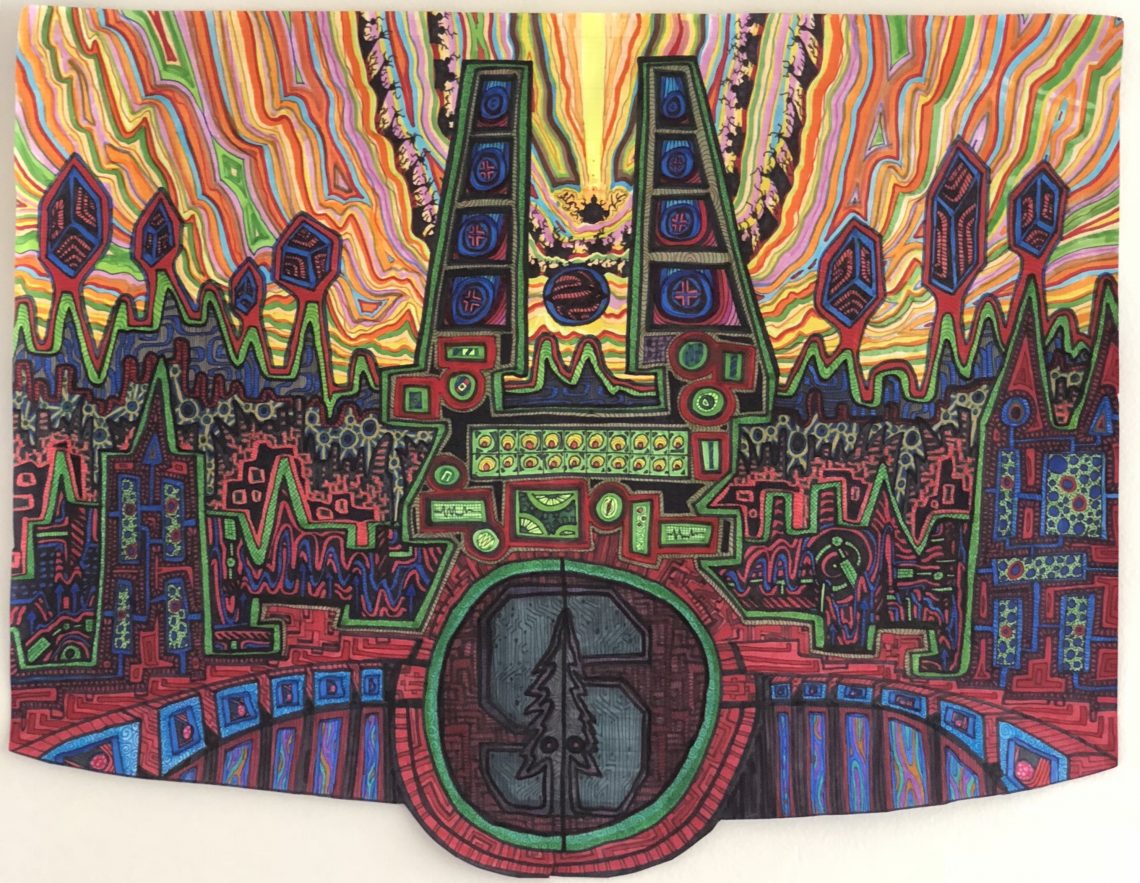

Both music and staging are also integral to the pair of chamber operas grouped under the collective title Visitations (to be performed at Bing Concert Hall on April 12 and 13). Indeed, composer Jonathan Berger points out, both works not only share the theme of inner, delusional voices but were created specifically to take advantage of Bing Hall’s unique design. “Its theater-in-the-round layout posed interesting constraints in terms of the drama and of how to work the music,” says Berger. “The solution we evolved is to make what happens onstage be the realization of the inner voices in each opera, while the audience literally becomes the skull of the protagonist.” Using a system of soundscapes based on ambisonic electroacoustics (created at Stanford’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics, or CCRMA), Berger devised a way to “move the sound around and direct it at specific points in the audience.” On a large scale, the ambisonics will mimic “how sounds are literally mapped in the brain as the hallucinations depicted in the operas emanate. I was inspired by imaging studies of sounds associated with hallucinations.”

Like Landfall, Visitations also represents an opportunity for first-time collaborations, in this case, a threefold one among Berger; librettist Dan O’Brien, a Los Angeles–based playwright and poet; and director Rinde Eckert. CCRMA will also devote its seventh annual Music and Brain Symposium (April 13), titled “Hearing Voices,” to exploring the real-life phenomena that are dramatized in the operas.

The first, Theotokia, involves the religious delusions of a schizophrenic whose consciousness the audience is made to experience from within. Berger’s score draws on elements of glossolalia, or “speaking in tongues,” and the forthright simplicity of Shaker hymns, which become abstracted and distorted. “Many people actually hear inner voices,” the composer remarks. “For years, delusional hallucinations were seen as pathological, but there seems to be a paradigm shift in how scholars are approaching this and thinking about the boundary between mental illness and deeply religious conviction.”

The other opera, The War Reporter, is based on O’Brien’s interviews with the Pulitzer Prize–winning combat journalist Paul Watson. It recounts how Watson became haunted by the voice of an American soldier whose corpse he had photographed during the Black Hawk Down incident in Mogadishu in 1993. Berger says this piece is “closer to narrative”—in contrast to Theotokia’s complex layering of identities—while the music “becomes more tonal and simpler as the protagonist’s inner thoughts become more gruesome in his experience of post- traumatic stress disorder.”

Eckert, who collaborated two years ago with sound sculptor Trimpin for Stanford Live’s presentation of the innovative opera The Gurs Zyklus, plans to make full use of Bing Hall’s signature sail and wave imagery in his staging. “The challenge,” he explains, “is to create a sense of landscape, of a liminal space, in which these visitations occur—in the one case as fantastic creatures of the imagination, in the other as remembered images the reporter can’t get rid of. Like water and the sea, like sound waves, these operas take place in a dynamic environment where things don’t remain statically in place.”