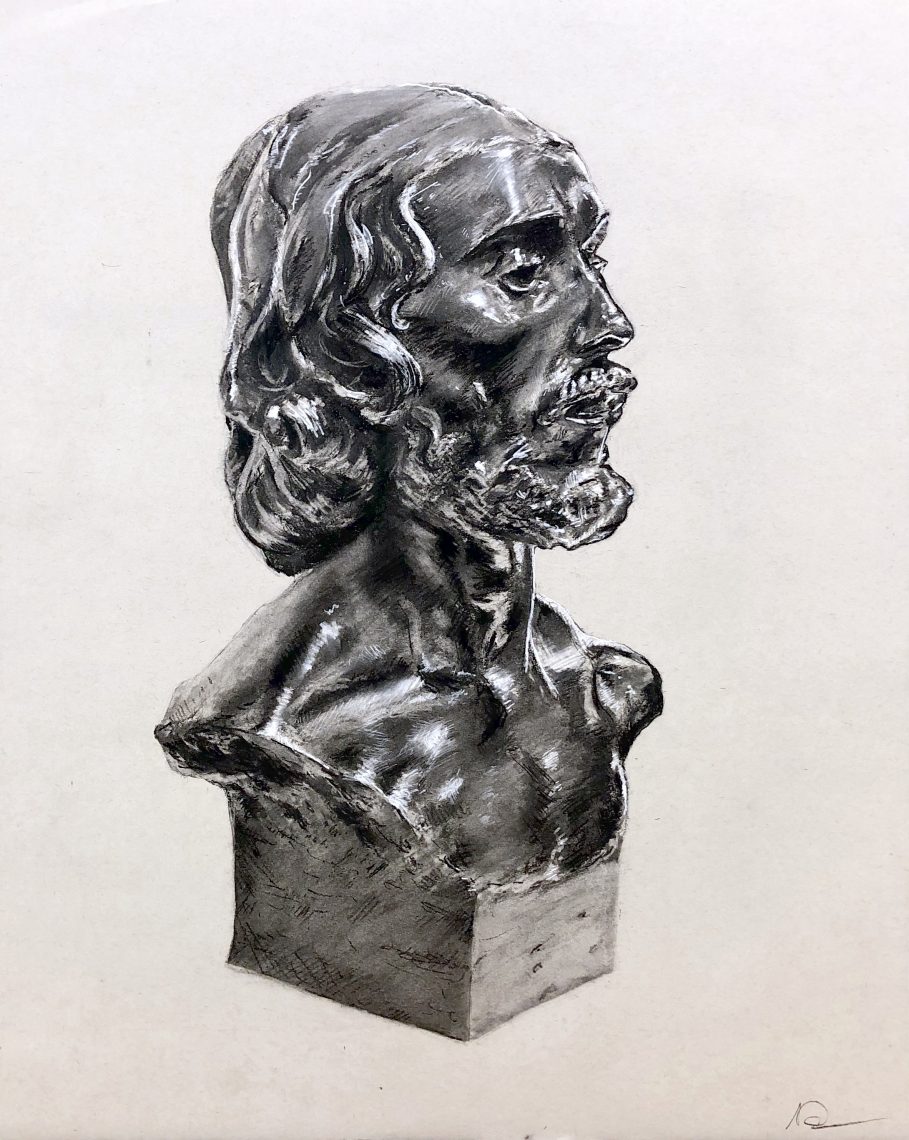

Visiting artist Ellen Lake discusses her work in the Experimental Media Art Lab.

L.A. CiceroStanford visiting artist Ellen Lake creates a cultural paradox across decades

The artist returns to obsolete technologies as a way to slow down time and reflect on both the past and the current media landscape.

Ellen Lake discovered a golden age of 16mm film. For a brief period the diacetate Kodachrome film used between 1939 and 1942 produced lush color and appears today perfectly preserved, as opposed to triacetate film that came into popular use in the mid-1940s and did not hold up nearly as well.

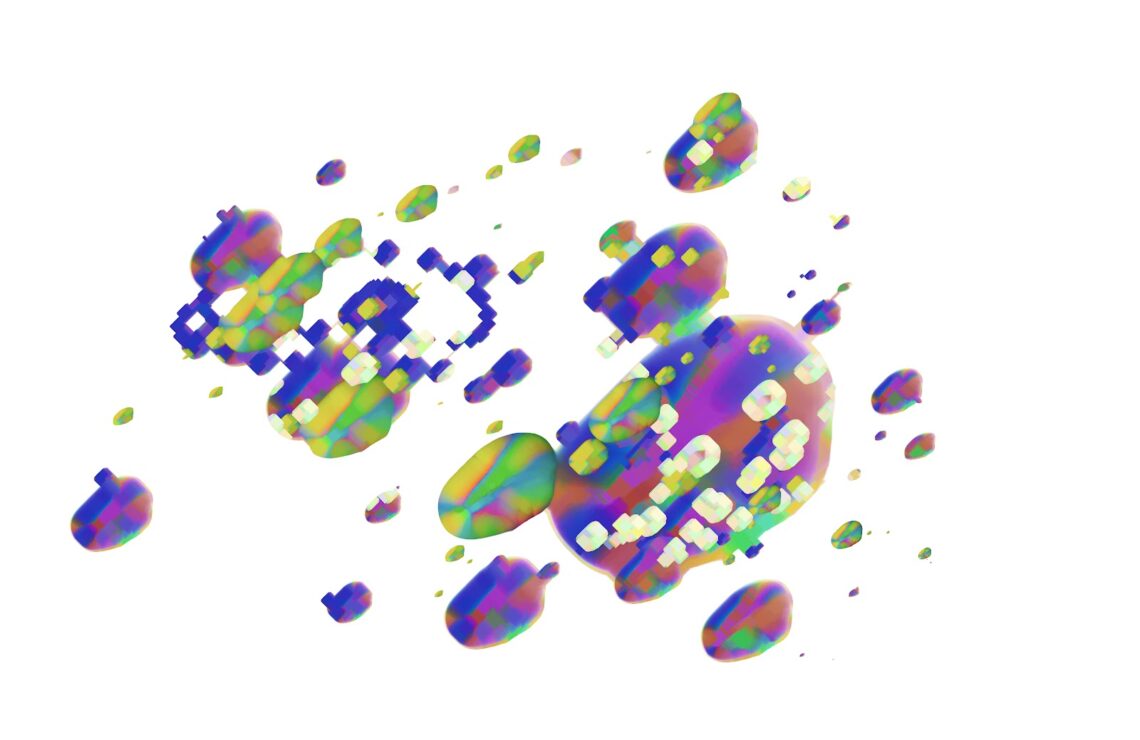

Lake, a visiting artist at Stanford’s Experimental Media Art Lab (EMA Lab), is mining 16mm films from that picture-perfect era to use in new work that explores the evolution of technology. Her work involves staged, clever interventions by combining contemporary elements with these film stills to create digital prints and short animations. The equipment and resources available 24/7 at the lab in the Nathan Cummings Art Building support her creative process.

“Ellen uses both classic and odd bits of cultural artifacts as her palette. She plays with our expectations of our objects and environments, as in Seaworthy, where a body floats dreamily through a frame focused on the Oakland docks, while massive container ships, cranes and sailboats crowd the background,” said lab colleague Gail Wight, an associate professor in Stanford’s Department of Art and Art History.

L.A. Cicero

“Call + Response melds 16mm film and cell phone video creating a cultural paradox across decades,” Wight said. “Her project for EMA continues with this time travel, fusing past and present objects – electronics, furniture, kitchenware – within solitary photographs, taunting us with the visual cues we use to establish time and place.”

Lake gave a lecture with fellow artist and Stanford alum Jeremiah Barber, MFA ’10, this week. Together the artists discussed film, documentation, old and new digital media, and their work created on the Stanford campus.

“In EMA, where we use so much technology, we’re often focused on the latest gadget. It’s wonderful to have Ellen sparking conversations with students about the nostalgia generated by our material world, and its inevitable ephemerality,” said Wight.

EMA Lab: We never close

Inspiration can strike at any moment, and so can the kick of caffeine, so access to the EMA Lab is available 24 hours a day to graduate art practice students and those taking undergraduate EMA classes. Elisabeth Kohnke manages the comings and goings of students as well as the resources within the lab and a large selection of equipment that can be checked out by students.

Kohnke is also the keeper of the door code. “Although access to the EMA Lab is somewhat restricted because of limited resources, I have been able to work with individuals and classes within the art department because of overlapping digital needs. These classes have included Michael Arcega‘s Sculpture 1 class, John Edmark’sanimation class and Faisal Abdu’Allah‘s printmaking class, which was funded by the Institute for Diversity in the Arts and the Committee on Black Performing Arts,” said Kohnke.

“I also work one-on-one with MFA students in the Art Practice Program and with MS students in our Joint Program in Design. The EMA Lab facilities and the equipment available for checkout provide a huge amount of resources not only for these graduate students but for any students enrolled in EMA courses as well.”

The EMA Lab offers a studio environment where students can work on digital, analog, electronic and alternative media art projects. Large-format printers, video and audio hardware and software, an analog electronics workstation, video microscopes and a wet work area all fit snugly into 650 square feet of space accessed via the inner courtyard of the Cummings Art Building.

Kohnke is looking forward to 2015, when the lab will relocate with the rest of the art and art history staff and faculty to the new McMurtry Building in the Arts District. Not only will the lab gain some much needed square footage in the new building, it will be united with its sister space, the Sound Studio.

EMA visiting artists receive a small stipend, round-the-clock access to the lab, library access and checkout privileges for all manner of art-making equipment. EMA visiting artists at Stanford include Susan Schwartzenberg, who worked with the School of Medicine; Camille Utterback, who worked with the School of Engineering; Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr from the University of Western Australia’s SymbioticA lab, who partnered with the Department of Bioengineering; and Heather Heise and Roddy Shrock, who worked with the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics.

Instant vintage

During the lecture this week, titled “Instant Vintage,” Lake talked about her current Stanford project combining old and new media, specifically using vintage home movies from the 1930s and ’40s alongside cellphone and digital media. This work continues investigations by artists who look, listen, push boundaries and explore perceptions of time.

Barber talked about his unique history of documenting actions in film, video and disposable media, focusing on the ways in which documentation can manipulate one’s experience, and how experience can overwhelm the document.

“I had two projects that I worked on as a grad student at Stanford, as well as several others that investigate the role of photography in recording events of significance. Nonexistent, Come to Me was a project I made for my thesis exhibition at Stanford during my final year of my MFA. Portrait of My Father was a performance made without an audience in a eucalyptus grove on campus,” Barber said.

The artist

Ellen Lake earned an MFA from Mills College in Oakland, Calif., where she studied sculpture, film and video, and installation. Work from her latest series combining vintage home movies with cellphone and digital media has been shown around the country at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Exit Art in New York, Multiplexer in Las Vegas and at several national and international film festivals.