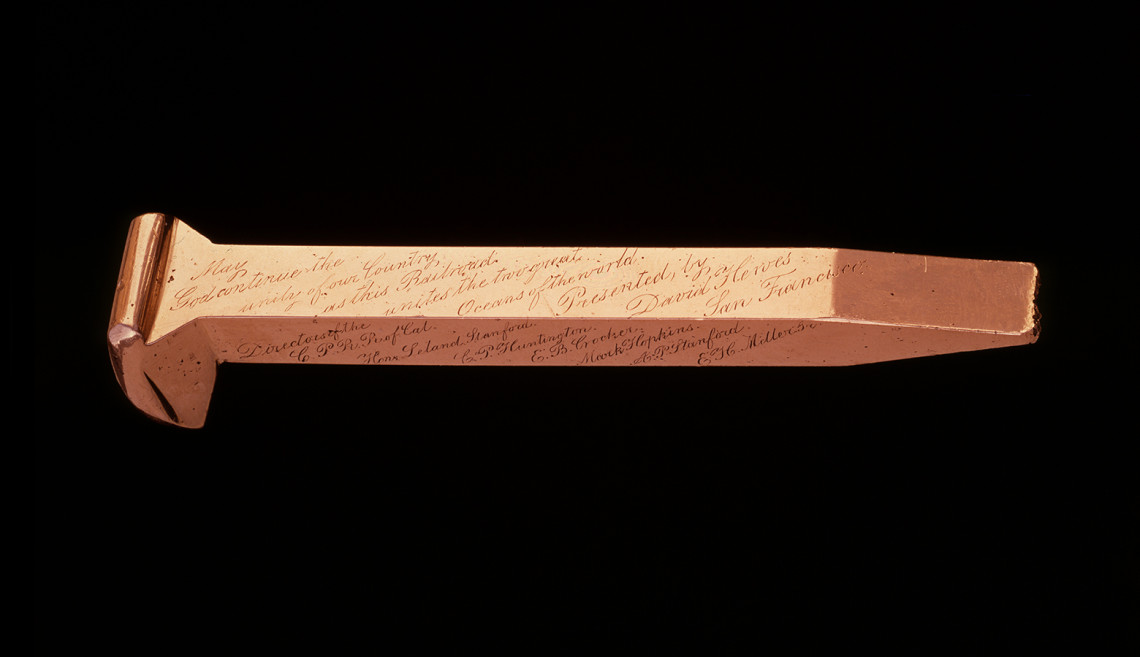

William T. Garrett Foundry, San Francisco

The Last SpikeStanford’s Cantor Arts Center partners with the Google Art Project, an international online art gallery

More than 100 high-resolution images from the Cantor are now available for in-depth research and examination.

Nothing compares to seeing a work of art in person, but there might also be nothing compared to examining a high- resolution image of a work of art that reveals details not visible to the naked eye – at least a naked eye viewing from behind a velvet rope or through protective Plexiglas.

The closer-than-you-can-get-in-person opportunity is available via the online gallery known as the Google Art Project – and the Cantor Arts Center is one of the latest international museums to join the project.

The Cantor submitted 105 high-resolution images of artwork spanning nearly 3,000 years to the Google Art Project.

The Google Art Project partnership is possible in part because of a multiyear digital imaging project already under way at the Cantor in which every work in the collection, over 30,000 objects, is being photographed in high-resolution format.

Accessibility to fragile or rarely displayed works of art via the Google Art Project is a boon to art history research.

Visitors to the Cantor website can access the works already photographed, about two-thirds of the collection, with the remainder expected to be accessible at the end of 2015.

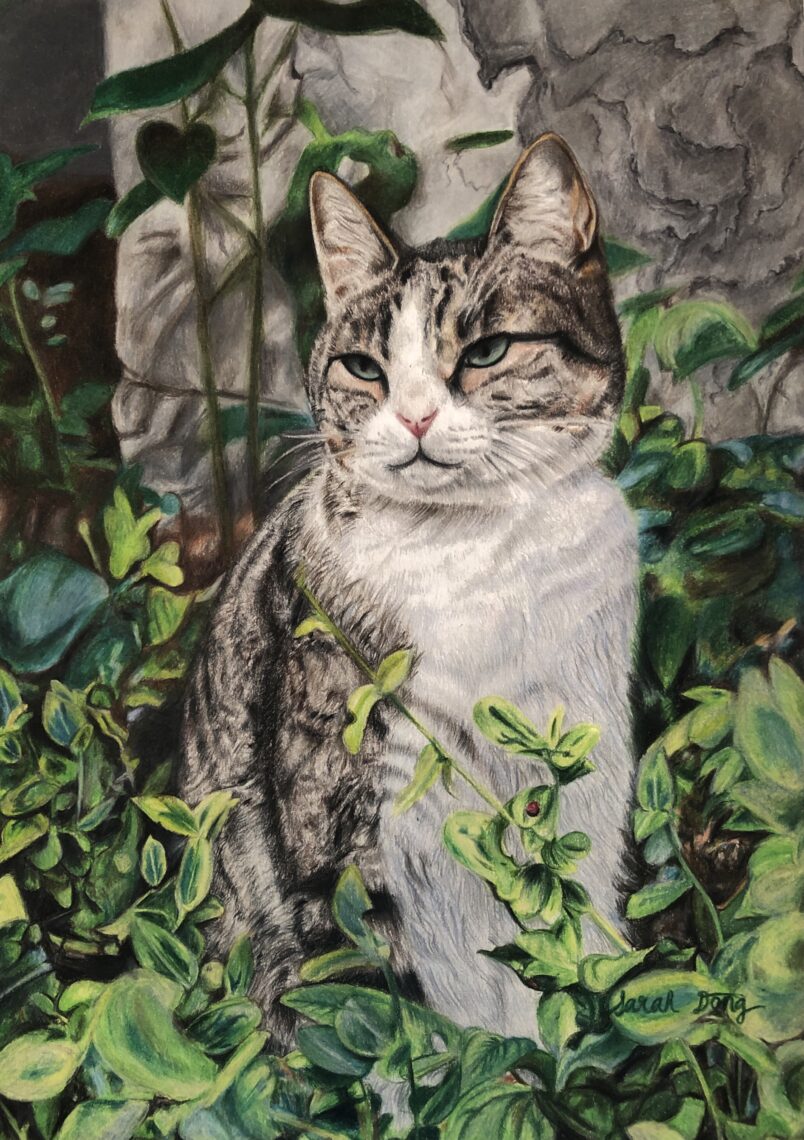

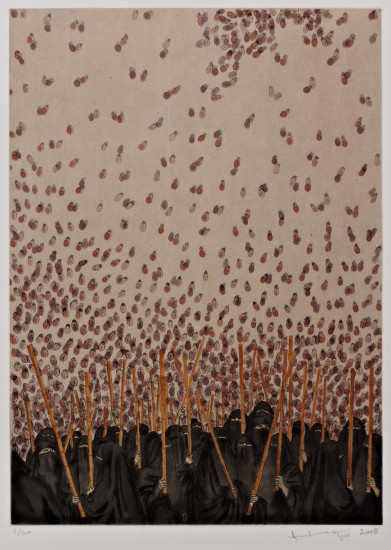

The broad range of objects recommended by the Cantor curatorial staff for the Google Art Project speaks to the impressive encyclopedic nature of the museum’s collection. Works submitted range from a seventh-century B.C. Egyptian limestone stele to a 15th-century woodcut by the German artist Albrecht Dürer to Pakistan-born Ambreen Butt’s Ladybugs etching dated 2008. “The project provides a little window into the collection that informs other museum professionals and the broader public about some of our treasures – and shows them how diverse the Cantor collection is,” said Elizabeth Mitchell, curator of prints, drawings and photographs.

Ladybugs

Recognizing that the project introduces the Cantor to a worldwide audience that might not be aware of its depth and diversity, the staff paid careful attention to countries, cultures and time periods – even the copyright-ridden 20th and 21st centuries.

Inclusion of modern and contemporary works in an online gallery is tricky because it requires jumping through the copyright hoops, but the Cantor staff was particularly interested in including art created by artists who were alive and active in the last 100 years.

Generally, if an artist has been dead for more than 70 years, the copyright restriction on the artist’s work is lifted. While many museum partners in the project have chosen to show older works that do not require permission from copyright holders, the Cantor staff decided that it was important to show more recent works, as they are an important part of the Cantor collection.

During the selection process, careful attention was also paid to artists close to campus. Two photographs by Stanford Leland’s friend (at least before their falling-out) Eadweard Muybridge represent the groundbreaking Muybridge collection at Cantor, considered one of the best in the world.

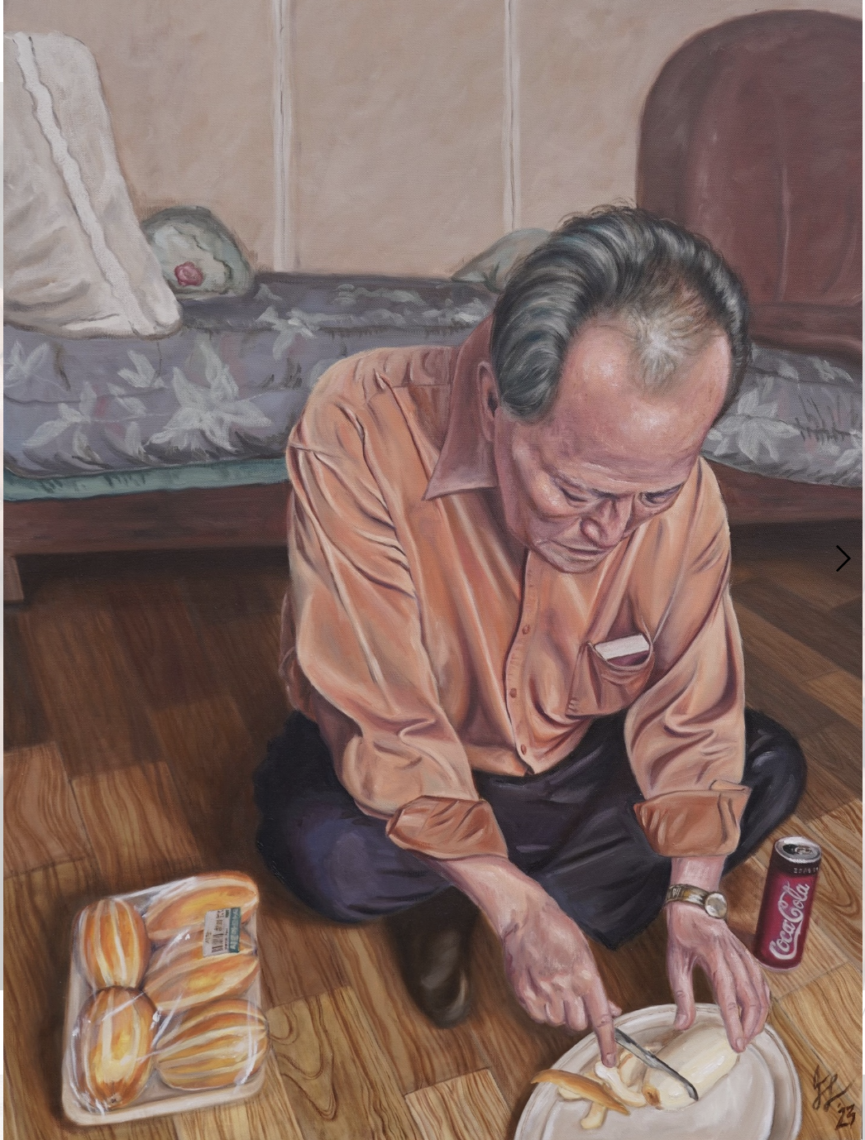

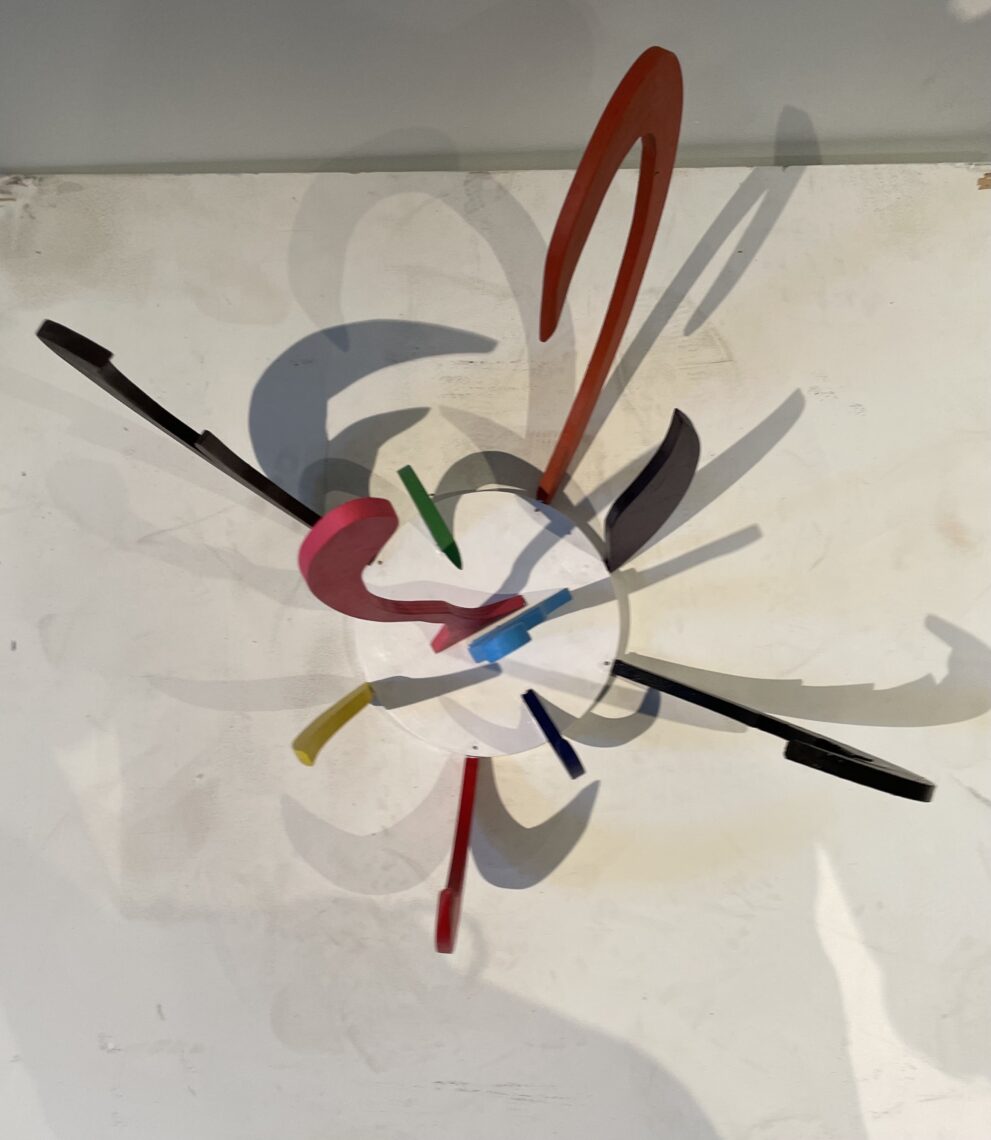

The significant large-scale painting Fall 1964 by Frank Lobdell, a Stanford visiting artist in 1965 and professor from 1966-1991, is also included. Other Bay Area art in the group of 105 images includes works by Joan Brown, Elmer Bischoff, William Keith, Manuel Neri and David Park.

Fall

History is also represented in the Cantor images. A golden spike, also knows as The Last Spike, dated 1869 and forged at the William T. Garrett Foundry in San Francisco, is the ceremonial spike linking the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads. Dents made by Senator Stanford when he tapped the spike with a silver hammer into a ceremonial tie are visible to the naked eye, but it is difficult to read the elegant but faint engraving (May God continue the unity of our Country, as this Railroad unites the two great Oceans of the world) without the aid of Google’s zoom feature.

Another bit of California and Stanford history submitted to the project is a sweet 6-by-5-inch daguerreotype of Jane Stanford as a very young girl with her mother, father and brother. Close examination reveals the texture of the mother’s headscarf, the father’s stern and formal expression, and the 10 shiny buttons on Jane’s brother’s jacket.

The aim is to increase the range and volume of material from the cultural world that is available for people to explore online, and in doing so, to democratize access to it and preserve it for future generations.

While the golden spike and many of the 105 objects are on long-term display (stable objects such as ceramics, metal works and paintings), there are other objects on the list (works on paper, textiles and photographs) that are displayed less frequently in order to comply with conservation recommendations. The daguerreotype of Jane Stanford’s family has never been exhibited to the public. Accessibility to fragile or rarely displayed works of art via the Google Art Project is a boon to art history research.

Mrs. Stanford’s Mother, Father, and Family

The high resolution of these images, combined with a custom-built zoom viewer, allows scholars and laymen alike to discover and examine minute aspects of paintings, prints, photographs, sculptures, textiles and ethnographic works that they may never have seen up close before.

The Google factor

Google has, of course, built in all sorts of online bells and whistles to make the site dynamic and social media-friendly. Visitors to the Google Art Project website can browse works by the artist’s name, the artwork, the type of art, the museum, country, collection or time period. Google+ and video hangouts are integrated into the site, allowing viewers to invite their friends to view and discuss their favorite works in a video chat or follow a guided tour from an expert to gain an appreciation of a particular topic or art collection.

The My Gallery feature allows users to save specific views of any of the artworks and build their own personalized galleries. Comments can be added to each painting and the whole gallery can then be shared with friends and family. It’s an ideal tool for students or groups to work on collaborative projects or collections.

In addition, a feature called “Compare” allows viewers to examine two pieces of artwork side-by-side to look at how an artist’s style evolved over time, to connect trends across cultures or to delve deeply into two parts of the same work.

According to Google, there are now more than 40,000 high-resolution objects available in the Art Project. Street View images now cover 200+ institutions in 40 countries, with more being added all the time.

The Art Project is part of the Google Cultural Institute dedicated to creating technology that helps the cultural community bring art, archives, heritage sites and other material online. The aim is to increase the range and volume of material from the cultural world that is available for people to explore online, and in doing so, to democratize access to it and preserve it for future generations.

“Given Stanford University’s unique history with Google – and our location in the Silicon Valley, the world’s technological capital –it is especially meaningful for the Cantor Arts Center to participate in the Google Art Project,” said Connie Wolf, Cantor’s director. “We appreciate the chance for individuals and scholars to learn more about the Cantor and its wide-ranging collection on an exciting new platform.”