Stanford art history graduate students will take a hands-on approach thanks to Mellon Grant

The Cantor Arts Center and the Department of Art and Art History forge a partnership to rethink the relationship between objects and academic study.

For an art lover, there is nothing quite like standing in front of a work of art. There’s the scale of the work, the texture of the paint, and the visceral emotional reaction that can only come through experience. For the museum curator, handling these objects – reading the artist’s scribbles on the back of a canvas, feeling the weight and texture of deckle-edged papers used in fine art prints, smelling the earthy odor of ancient pottery, counting the threads of a fragile textile – contributes to a greater understanding of the work of art and the artist. Minimal, careful handling is done in the interest of scholarship and discovery – and it’s also a thrill.

Stanford art history graduate students are going to be able to roll up their sleeves and use their hands because the university has received a $500,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to strengthen collaboration between the Department of Art and Art History and the Cantor Arts Center. Over the next three and a half years, the grant will support new initiatives within the art history graduate program that use the museum’s collections in coursework and research and provide curatorial training for students.

“In the history of art, there is a sense that the museum of objects is separate from what is going on in the academy, where you are taught from reproductions,” said Nancy Troy, head of the Department of Art and Art History. Every art history student has a story about seeing a work of art for the first time after only studying it on a screen or from a textbook. Who isn’t surprised at the diminutive size of the Mona Lisa?

The Mellon Foundation grant brings together scholarship and works of art in order to facilitate graduate training in an object-based environment, where students study and experience the thrill of handling physical objects instead of learning purely from projected images.

Jumpstarting collaboration

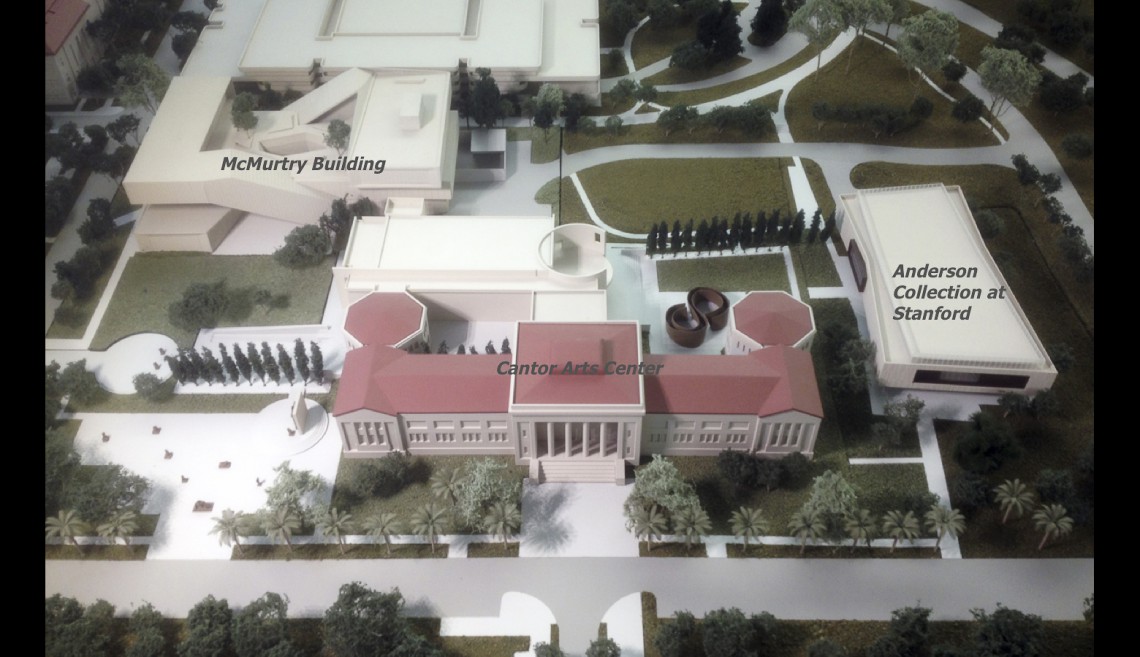

This separation of the museum and the academy is echoed geographically on the Stanford campus in the distance between Cantor and the Cummings Art Building, home to the Department of Art and Art History as well as the Art and Architecture Library. With construction of the McMurtry Building and the Anderson Collection at Stanford University now underway in the developing arts district, this distance is being compressed.

“The Cantor has to rethink itself and reposition the role that it will play as an anchor for the arts on campus,” said Connie Wolf, Cantor’s director. “The art and art history building is going to be side-by-side with the museum for the first time, but having buildings next door to each other isn’t enough. The Mellon Grant is really allowing us to start creating these meaningful connections and to launch them in a very significant way.”

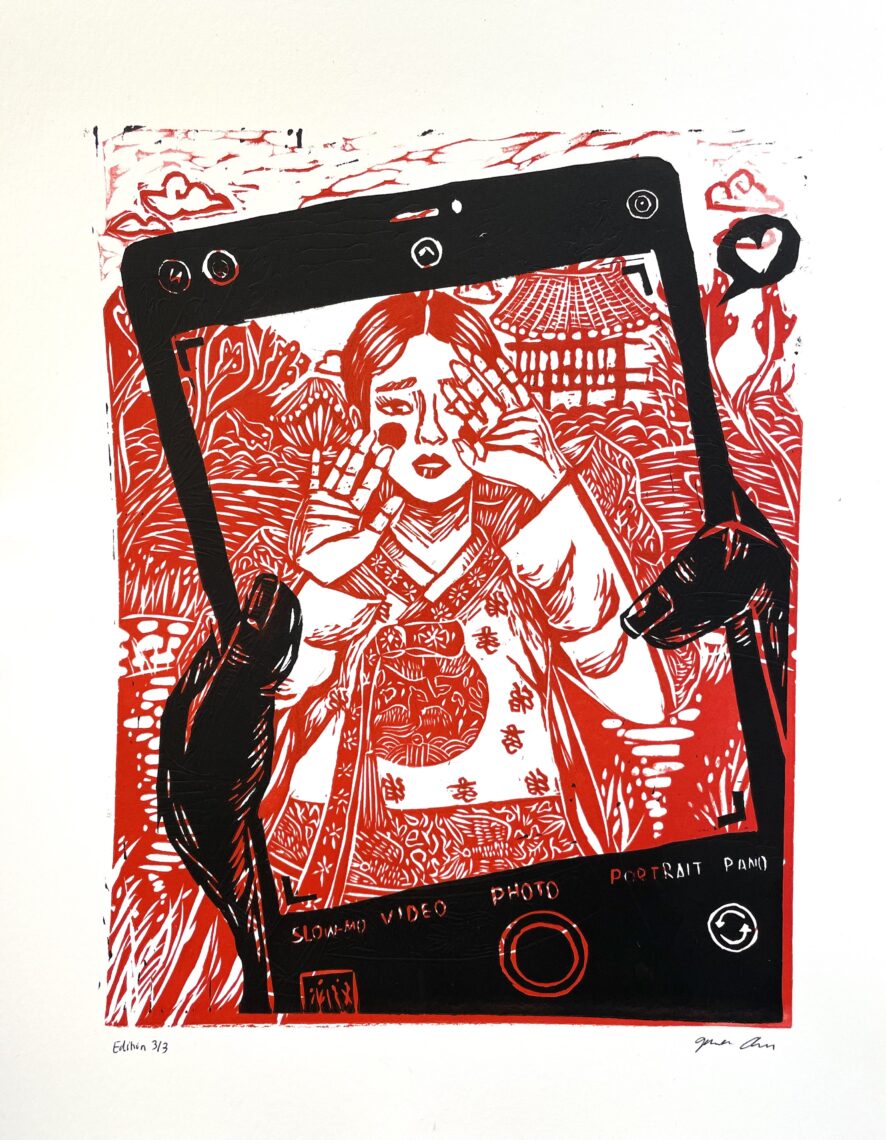

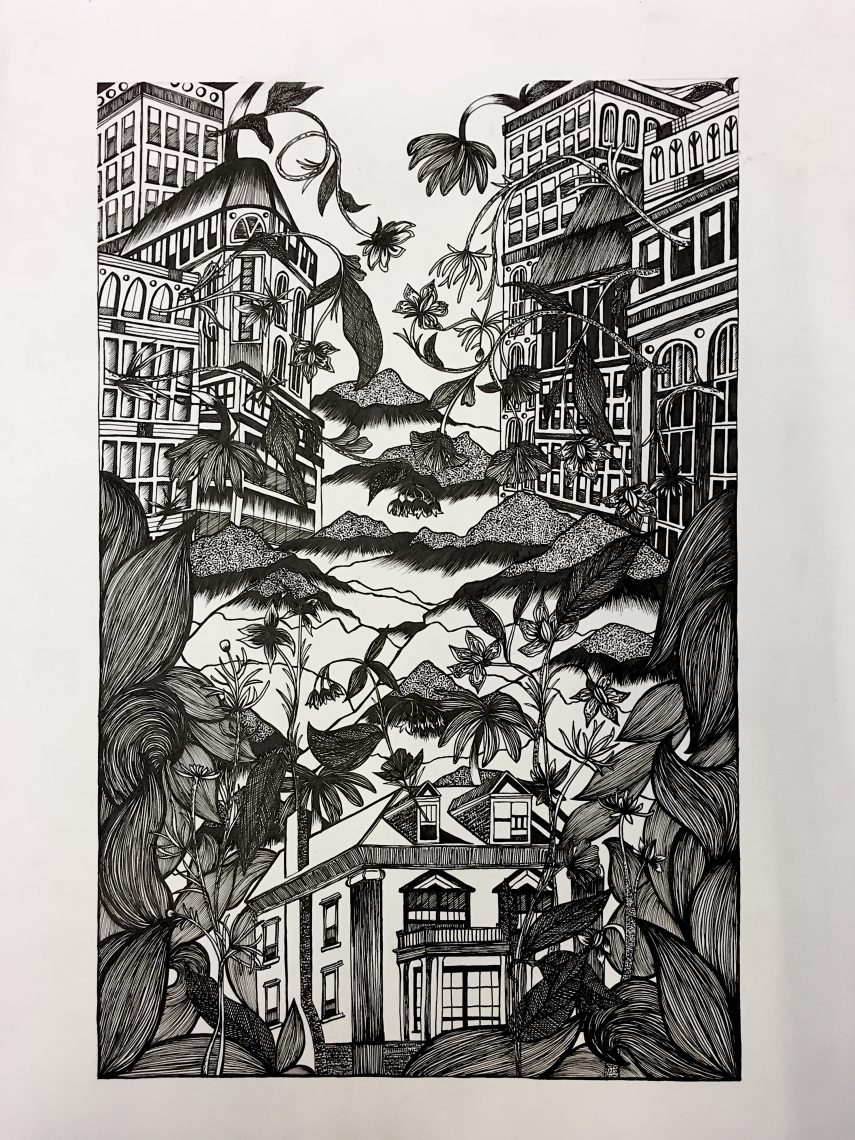

The grant will be able to jumpstart collaboration between the two institutions by funding a series of six new programs that will strengthen students’ familiarity with objects. New seminars will focus on the history of collecting and display, museum conservation, and the study of objects in Cantor’s extensive collections. One two-quarter “seminar plus” course on curatorial strategies will culminate in a class-curated exhibition. Another will focus on reinstalling the Asian art galleries, tackling Asian art’s complexity and diversity while exploring fresh angles on the problems of categorization and representation. Finally, five curatorial research assistantships at the Cantor will enable students to curate their own exhibitions, working directly with the Cantor’s collections and pursuing their specific research interests.

Changing the DNA of art history education

Beyond supplementing graduate students’ educational experience through closer interaction with Cantor, the museum benefits from the new ideas students bring.

“Students provide new perspectives, new insights, new ways of thinking,” said Wolf. “It’s going to be really exciting to see what they are interested in studying. I’m always interested in the public dimension of their research. I love working with people to think about how you can create a really meaningful dialogue with a broader public so that your research doesn’t live in a small community.”

Troy believes that giving students exposure to museum work will help them grow intellectually and better their chances of finding employment in an increasingly competitive job market.

“Students need some serious object-based training if they are going to be able to maximize their potential to understand various different approaches,” she said. “The more arrows you have in your quiver, the more targets you will be able to hit.”

Wolf hopes the new courses and the research assistantships become an integral part of the art history program: “I want to make this so important and essential to our education process and the role of the museum that at the end of this period it is embedded in the DNA of who we are.”